Info

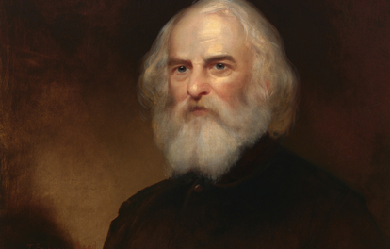

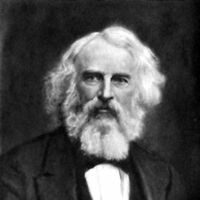

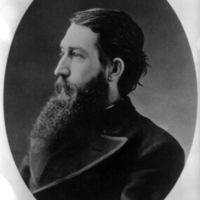

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator whose works include "Paul Revere's Ride", The Song of Hiawatha, and Evangeline. He was also the first American to translate Dante Alighieri's The Divine Comedy and was one of the five Fireside Poets. Longfellow was born in Portland, Maine, then part of Massachusetts, and studied at Bowdoin College. After spending time in Europe he became a professor at Bowdoin and, later, at Harvard College. His first major poetry collections were Voices of the Night (1839) and Ballads and Other Poems (1841). Longfellow retired from teaching in 1854 to focus on his writing, living the remainder of his life in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in a former headquarters of George Washington. His first wife, Mary Potter, died in 1835 after a miscarriage. His second wife, Frances Appleton, died in 1861 after sustaining burns from her dress catching fire. After her death, Longfellow had difficulty writing poetry for a time and focused on his translation. He died in 1882.

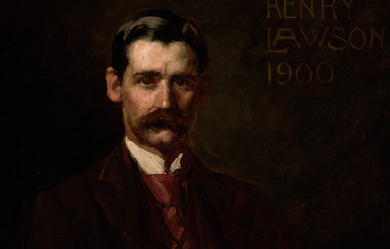

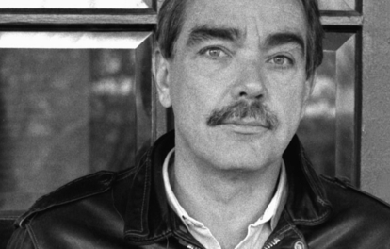

Henry Archibald Hertzberg Lawson (17 June 1867 – 2 September 1922) was an Australian writer and poet. Along with his contemporary Banjo Paterson, Lawson is among the best-known Australian poets and fiction writers of the colonial period and is often called Australia's “greatest short story writer”. He was the son of the poet, publisher and feminist Louisa Lawson.

#Australians #XIXCentury #XXCentury

Rare & Strange...Lover of Wine, Sports, Skulls, The Sun, All Things Fast, Giving & Taking Chances, People Watching, Music, Poetry, Animals, Dialogue, Sensuality, Sexuality, Passion & Passionate People, Confidence, Art, Movies, Conversations, Romance, Philosophy & Johnny Depp.....Watching movies that make you think - like A waking life or with great dialogue. It's all about the lighting... What makes us different, you & I? I'm on my life mission of seeking the strange, yet the similar, the one who will make me think, make me not think, who will drive me wild with words, passion and love. I wear my heart on my sleeve and won't stop to let the world take away my spirit. I refuse to settle even if it means I never stop ...but I know he's out there my eclectic twin soul who will love adventure, random rants, giving and caring for others, fitting in between the cracks with me and standing out in the crowd too. Intelligent and Cultured , both city and country lover, who will pack up run through the mountains taking random photos of cemeteries and visions in the clouds, who will jump on a horse and ride a wild ride with me...a best friend, a soul mate, the other half who inspires me and I inspire he and long talks with large glasses of wine and endless nights in electric passion ...tantric, twisted, non-judging just accepting each other completely, swallowing each other ...

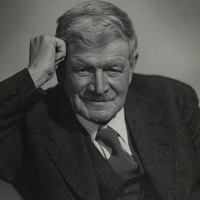

Philip Arthur Larkin (9 August 1922 – 2 December 1985) was an English poet and novelist. His first book of poetry, The North Ship, was published in 1945, followed by two novels, Jill (1946) and A Girl in Winter (1947), but he came to prominence in 1955 with the publication of his second collection of poems, The Less Deceived, followed by The Whitsun Weddings (1964) and High Windows (1974). He was the recipient of many honours, including the Queen's Gold Medal for Poetry. He was offered, but declined, the position of poet laureate in 1984, following the death of John Betjeman.

Andrew Lang (31 March 1844– 20 July 1912) was a Scottish poet, novelist, literary critic, and contributor to the field of anthropology. He is best known as a collector of folk and fairy tales. The Andrew Lang lectures at the University of St Andrews are named after him. Lang was born in Selkirk. He was the eldest of the eight children born to John Lang, the town clerk of Selkirk, and his wife Jane Plenderleath Sellar, who was the daughter of Patrick Sellar, factor to the first duke of Sutherland. On 17 April 1875, he married Leonora Blanche Alleyne, youngest daughter of C. T. Alleyne of Clifton and Barbados.

Amy Lawrence Lowell (February 9, 1874 – May 12, 1925) was an American poet of the imagist school from Brookline, Massachusetts, who posthumously won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1926. Amy was born into Brookline’s Lowell family, sister to astronomer Percival Lowell and Harvard president Abbott Lawrence Lowell. She never attended college because her family did not consider it proper for a woman to do so. She compensated for this lack with avid reading and near-obsessive book collecting. She lived as a socialite and travelled widely, turning to poetry in 1902 (age 28) after being inspired by a performance of Eleonora Duse in Europe.

#Americans #Lesbian #PulitzerPrize #Women

I love poetry. I write poetry based on my experience in life and love and the songs I listen to. I first started writing for school, but I'm literally addicted to poetry now. It's my escape. I have been through so many things in my life I should not have had to go through, especially since I'm only 14. But it all comes out in my poetry. I love watching crime shows like Criminal Minds and NCIS. I'm obsessed with TV news reports about such things as crime, train derailments, car accidents, and fires. It's just the way I am. They say music, especially rock music, takes away your pain, whether it be physical, emotional, spiritual, or mental. I learned it's not true. It just makes it better temporarily, but then makes it worse.

Edward Lear (12 or 13 May 1812 – 29 January 1888) was an English artist, illustrator, author and poet, and is known now mostly for his literary nonsense in poetry and prose and especially his limericks, a form he popularised. His principal areas of work as an artist were threefold: as a draughtsman employed to illustrate birds and animals; making coloured drawings during his journeys, which he reworked later, sometimes as plates for his travel books; as a (minor) illustrator of Alfred Tennyson's poems. As an author, he is known principally for his popular nonsense works, which use real and invented English words. Early years Lear was born into a middle-class family in the village of Holloway near London, the penultimate of twenty-one children (and youngest to survive) of Ann Clark Skerrett and Jeremiah Lear. He was raised by his eldest sister, also named Ann, 21 years his senior. Owing to the family's limited finances, Lear and his sister were required to leave the family home and live together when he was aged four. Ann doted on Edward and continued to act as a mother for him until her death, when he was almost 50 years of age. Lear suffered from lifelong health afflictions. From the age of six he suffered frequent grand mal epileptic seizures, and bronchitis, asthma, and during later life, partial blindness. Lear experienced his first seizure at a fair near Highgate with his father. The event scared and embarrassed him. Lear felt lifelong guilt and shame for his epileptic condition. His adult diaries indicate that he always sensed the onset of a seizure in time to remove himself from public view. When Lear was about seven years old he began to show signs of depression, possibly due to the instability of his childhood. He suffered from periods of severe melancholia which he referred to as "the Morbids.” Artist Lear was already drawing "for bread and cheese" by the time he was aged 16 and soon developed into a serious "ornithological draughtsman" employed by the Zoological Society and then from 1832 to 1836 by the Earl of Derby, who kept a private menagerie at his estate Knowsley Hall. Lear's first publication, published when he was 19 years old, was Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots in 1830. His paintings were well received and he was compared favourably with the naturalist John James Audubon. Among other travels, he visited Greece and Egypt during 1848–49, and toured India and Ceylon (Sri Lanka) during 1873–75. While travelling he produced large quantities of coloured wash drawings in a distinctive style, which he converted later in his studio into oil and watercolour paintings, as well as prints for his books. His landscape style often shows views with strong sunlight, with intense contrasts of colour. Throughout his life he continued to paint seriously. He had a lifelong ambition to illustrate Tennyson's poems; near the end of his life a volume with a small number of illustrations was published. Relationships Lear's most fervent and painful friendship involved Franklin Lushington. He met the young barrister in Malta in 1849 and then toured southern Greece with him. Lear developed an undoubtedly homosexual passion for him that Lushington did not reciprocate. Although they remained friends for almost forty years, until Lear's death, the disparity of their feelings for one another constantly tormented Lear. Indeed, none of Lear's attempts at male companionship were successful; the very intensity of Lear's affections seemingly doomed the relationships. The closest he came to marriage with a woman was two proposals, both to the same person 46 years his junior, which were not accepted. For companions he relied instead on friends and correspondents, and especially, during later life, on his Albanian Souliote chef, Giorgis, a faithful friend and, as Lear complained, a thoroughly unsatisfactory chef. Another trusted companion in Sanremo was his cat, Foss, which died in 1886 and was buried with some ceremony in a garden at Villa Tennyson. San Remo and death Lear travelled widely throughout his life and eventually settled in Sanremo, on his beloved Mediterranean coast, in the 1870s, at a villa he named "Villa Tennyson". Lear was known to introduce himself with a long pseudonym: "Mr Abebika kratoponoko Prizzikalo Kattefello Ablegorabalus Ableborinto phashyph" or "Chakonoton the Cozovex Dossi Fossi Sini Tomentilla Coronilla Polentilla Battledore & Shuttlecock Derry down Derry Dumps" which he based on Aldiborontiphoskyphorniostikos. After a long decline in his health, Lear died at his villa in 1888, of the heart disease from which he had suffered since at least 1870. Lear's funeral was said to be a sad, lonely affair by the wife of Dr. Hassall, Lear's physician, none of Lear's many lifelong friends being able to attend. Lear is buried in the Cemetery Foce in San Remo. On his headstone are inscribed these lines about Mount Tomohrit (in Albania) from Tennyson's poem To E.L. [Edward Lear], On His Travels in Greece: all things fair. With such a pencil, such a pen. You shadow forth to distant men, I read and felt that I was there. The centenary of his death was marked in Britain with a set of Royal Mail stamps in 1988 and an exhibition at the Royal Academy. Lear's birthplace area is now marked with a plaque at Bowman's Mews, Islington, in London, and his bicentenary during 2012 was celebrated with a variety of events, exhibitions and lectures in venues across the world including an International Owl and Pussycat Day on his birthday. References Wikipedia – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Lear

Nicholas Vachel Lindsay (November 10, 1879 – December 5, 1931) was an American poet. He is considered a founder of modern singing poetry, as he referred to it, in which verses are meant to be sung or chanted. Crushed by financial worry and in failing health from his six-month road trip, Lindsay sank into depression. While in New York in 1905 Lindsay turned to poetry in earnest. He tried to sell his poems on the streets. Self-printing his poems, he began to barter a pamphlet titled “Rhymes To Be Traded For Bread”, which he traded for food as a self-perceived modern version of a medieval troubadour. On December 5, 1931, he committed suicide by drinking a bottle of Lysol. His last words were: “They tried to get me; I got them first!”

#Americans #Suicide #XIXCentury #XXCentury

I'm a social science student with an interest in philosophy, sociology and anthropology particularly. I would describe myself as a highly sensitive person but forever the optimist. Music is more than a hobby of mine, it is a way of life. I wear my heart on my sleeve and because of this I am a songwriter, musician and occasional poet. Instagram username- Marnoldkins

Richard Lovelace (1618–1657) was an English poet in the seventeenth century. He was a cavalier poet who fought on behalf of the king during the Civil war. His best known works are To Althea, from Prison, and To Lucasta, Going to the Warres. Richard Lovelace attended Oxford University and he was praised by one of his contemporaries, Anthony Wood. for being “the most amiable and beautiful person that ever eye beheld; a person also of innate modesty, virtue and courtly deportment, which made him then, but especially after, when he retired to the great city, much admired and adored by the female sex"

Raised in Summerville, South Carolina, Michelle is the oldest of three children and an Army veteran whose personal interests of study include Feng Shui, Planetary science, Botany, and Buddhism. Hobbies include music theory, poetry, video games, salt-water fishing, and stargazing. Michelle Lalonde has AAS in Horticulture, is a South Carolina certified Nurserymen #408, with the South Carolina Nursery and Landscape Association (SCNLA); focused interests in Residential Landscape Design, Commercial Landscape Design, Landscape Management, and Golf Course Maintenance with over 15 years hands-on experience. Author of "Landscaper’s Guide to the South;" a non-fiction guide to easy landscaping for the student, homeowner and landscape professional, Michelle began this book as a Horticulture student to make the difficult and time-consuming endeavor of planning a landscape simple and guess proof, then added over 15 years of experience and training as a skilled horticulturist and landscape designer to complete the project. Michelle also holds a BA in Creative Writing with a minor in Communications, an AAS in Nursing (Army), and Paralegal Studies.

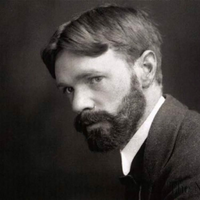

David Herbert Richards Lawrence (11 September 1885 – 2 March 1930) was an English novelist, poet, playwright, essayist, literary critic and painter who published as D. H. Lawrence. His collected works represent an extended reflection upon the dehumanising effects of modernity and industrialisation. In them, Lawrence confronts issues relating to emotional health and vitality, spontaneity, and instinct. Lawrence’s opinions earned him many enemies and he endured official persecution, censorship, and misrepresentation of his creative work throughout the second half of his life, much of which he spent in a voluntary exile which he called his “savage pilgrimage”. At the time of his death, his public reputation was that of a pornographer who had wasted his considerable talents. E. M. Forster, in an obituary notice, challenged this widely held view, describing him as, “The greatest imaginative novelist of our generation”. Later, the influential Cambridge critic F. R. Leavis championed both his artistic integrity and his moral seriousness, placing much of Lawrence's fiction within the canonical “great tradition” of the English novel. Lawrence is now valued by many as a visionary thinker and significant representative of modernism in English literature.

#English Modern

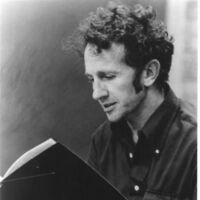

Philip Levine (January 10, 1928– February 14, 2015) was a Pulitzer Prize-winning American poet best known for his poems about working-class Detroit. He taught for more than thirty years in the English department of California State University, Fresno and held teaching positions at other universities as well. He served on the Board of Chancellors of the Academy of American Poets from 2000 to 2006, and was appointed Poet Laureate of the United States for 2011–2012. Biography Philip Levine grew up in industrial Detroit, the second of three sons and the first of identical twins of Jewish immigrant parents. His father, Harry Levine, owned a used auto parts business, his mother, Esther Priscol (Prisckulnick) Levine, was a bookseller. When Levine was five years old, his father died. While growing up, he faced the anti-Semitism embodied by Father Coughlin, the pro-Nazi radio priest. Levine started to work in car manufacturing plants at the age of 14. Detroit Central High School graduated him in 1946 and he went to college at Wayne University (now Wayne State University) in Detroit, where he began to write poetry, encouraged by his mother, to whom he dedicated the book of poems, The Mercy. Levine earned his A.B. in 1950 and went to work for Chevrolet and Cadillac in what he called “stupid jobs.” He married his first wife, Patty Kanterman, in 1951. The marriage lasted until 1953. In 1953, he attended the University of Iowa without registering, studying with, among others, poets Robert Lowell and John Berryman, the latter of whom Levine called his “one great mentor.” In 1954, he earned a mail-order masters degree with a thesis on John Keats’ “Ode to Indolence,” and married actress Frances J. Artley. He returned to the University of Iowa teaching technical writing, completing his Master of Fine Arts degree in 1957. The same year, he was awarded the Jones Fellowship in Poetry at Stanford University. In 1958, he joined the English department at California State University in Fresno, where he taught until his retirement in 1992. He also taught at many other universities, among them New York University as Distinguished Writer-in-Residence, Columbia, Princeton, Brown, Tufts, and the University of California at Berkeley. Levine and his wife had made their homes in Fresno and Brooklyn. He died of pancreatic cancer on February 14, 2015, age 87. Work The familial, social, and economic world of twentieth-century Detroit is one of the major subjects of Levine’s life work. His portraits of working class Americans and his continuous examination of his Jewish immigrant inheritance (both based on real life and described through fictional characters) has left a testimony of mid-twentieth century American life. Levine’s working experience lent his poetry a profound skepticism with regard to conventional American ideals. In his first two books, On the Edge (1963) and Not This Pig (1968), the poetry dwells on those who suddenly become aware that they are trapped in some murderous processes not of their own making. In 1968, Levine signed the “Writers and Editors War Tax Protest” pledge, vowing to refuse to make tax payments in protest against the Vietnam War. In his first two books, Levine was somewhat traditional in form and relatively constrained in expression. Beginning with They Feed They Lion, typically Levine’s poems are free-verse monologues tending toward trimeter or tetrameter. The music of Levine’s poetry depends on tension between his line-breaks and his syntax. The title poem of Levine’s book 1933 (1974) is an example of the cascade of clauses and phrases one finds in his poetry. Other collections include The Names of the Lost, A Walk with Tom Jefferson, New Selected Poems, and the National Book Award-winning What Work Is. On November 29, 2007 a tribute was held in New York City in anticipation of Levine’s eightieth birthday. Among those celebrating Levine’s career by reading Levine’s work were Yusef Komunyakaa, Galway Kinnell, E. L. Doctorow, Charles Wright, Jean Valentine and Sharon Olds. Levine read several new poems as well. Awards * 2013 Academy of American Poets Wallace Stevens Award * 2011 Appointed Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress (United States Poet Laureate) * 1995 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry– The Simple Truth (1994) * 1991 National Book Award for Poetry and Los Angeles Times Book Prize– What Work Is * 1987 Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize from the Modern Poetry Association and the American Council for the Arts * 1981 Levinson Prize from Poetry magazine * 1980 Guggenheim Foundation fellowship * 1980 National Book Award for Poetry– Ashes: Poems New and Old * 1979 National Book Critics Circle Award– Ashes: Poems New and Old– 7 Years from Somewhere * 1978 Harriet Monroe Memorial Prize from Poetry * 1977 Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize from the Academy of American Poets– The Names of the Lost (1975) * 1973 American Academy of Arts and Letters Award, Frank O’Hara Prize, Guggenheim Foundation fellowship Published works Poetry collections * News of the World, Random House, Inc., 2009, ISBN 978-0-307-27223-2 * Stranger to Nothing: Selected Poems, Bloodaxe Books, UK, 2006, ISBN 978-1-85224-737-9 * Breath Knopf, 2004, ISBN 978-1-4000-4291-3; reprint, Random House, Inc., 2006, ISBN 978-0-375-71078-0 * The Mercy, Random House, Inc., 1999, ISBN 978-0-375-70135-1 * Unselected Poems, Greenhouse Review Press, 1997, ISBN 978-0-9655239-0-5 * The Simple Truth, Alfred A. Knopf, 1994, ISBN 978-0-679-43580-8; Alfred A. Knopf, 1996, ISBN 978-0-679-76584-4 * What Work Is, Knopf, 1992, ISBN 978-0-679-74058-2 * New Selected Poems, Knopf, 1991, ISBN 978-0-679-40165-0 * A Walk With Tom Jefferson, A.A. Knopf, 1988, ISBN 978-0-394-57038-9 * Sweet Will, Atheneum, 1985, ISBN 978-0-689-11585-1 * Selected Poems, Atheneum, 1984, ISBN 978-0-689-11456-4 * One for the Rose, Atheneum, 1981, ISBN 978-0-689-11223-2 * 7 Years From Somewhere, Atheneum, 1979, ISBN 978-0-689-10974-4 * Ashes: Poems New and Old, Atheneum, 1979, ISBN 978-0-689-10975-1 * The Names of the Lost, Atheneum, 1976 * 1933, Atheneum, 1974, ISBN 978-0-689-10586-9 * They Feed They Lion, Atheneum, 1972 * Red Dust (1971) * Pili’s Wall, Unicorn Press, 1971; Unicorn Press, 1980 * Not This Pig, Wesleyan University Press, 1968, ISBN 978-0-8195-2038-8; Wesleyan University Press, 1982, ISBN 978-0-8195-1038-9 * On the Edge (1963) Essays * The Bread of Time (1994) Translations * Off the Map: Selected Poems of Gloria Fuertes, edited and translated with Ada Long (1984) * Tarumba: The Selected Poems of Jaime Sabines, edited and translated with Ernesto Trejo (1979) Interviews * Don’t Ask, University of Michigan Press, 1981, ISBN 978-0-472-06327-7 * Moyers & Company, on December 29, 2013, Philip Levine reads some of his poetry and explores how his years working on Detroit’s assembly lines inspired his poetry. * “Interlochen Center for the Arts”, Interview with Interlochen Arts Academy students on March 17, 1977. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip_Levine_(poet)

The Split Man sculpture represents the mental state of the dysfunctional human (here represented as a 30 year old). This human (male or female) is falling apart because he/she cannot or will not dedicate his or her life to one goal, consequently can’t create his/her true self, and, by failing to apply that true self, achieve self-realization. Failure to make the goal a reality results in en-darkenment, to wit, (energy) depression. Achievement of the goal results in en-lightenment, to wit, (energy) elation, and the experience of rapturous joy. The Split Man wants to die, in fact, needs to die. He/she needs to return to his/her original state in order to recover his/her essential self, therefore his or her unique life purpose (read: dharma). It’s the 100% application of life purpose (or dharma) that leads to the experience of the true self. Split Man, Victoria’s Way, Co Wicklow Ireland

Charles Lamb (London, 10 February 1775 – Edmonton, 27 December 1834) was an English essayist, best known for his Essays of Elia and for the children's book Tales from Shakespeare, which he produced with his sister, Mary Lamb (1764–1847). Lamb has been referred to by E.V. Lucas, his principal biographer, as "the most lovable figure in English literature”. Youth and schooling Lamb was the son of Elizabeth Field and John Lamb. Lamb was the youngest child, with an 11 year older sister Mary, an even older brother John, and 4 other siblings who did not survive their infancy. John Lamb (father), who was a lawyer's clerk, spent most of his professional life as the assistant and servant to a barrister by the name of Samuel Salt who lived in the Inner Temple in London. It was there in the Inner Temple in Crown Office Row, that Charles Lamb was born and spent his youth. Lamb created a portrait of his father in his "Elia on the Old Benchers" under the name Lovel. Lamb's older brother was too much his senior to be a youthful companion to the boy but his sister Mary, being born eleven years before him, was probably his closest playmate. Lamb was also cared for by his paternal aunt Hetty, who seems to have had a particular fondness for him. A number of writings by both Charles and Mary suggest that the conflict between Aunt Hetty and her sister-in-law created a certain degree of tension in the Lamb household. However, Charles speaks fondly of her and her presence in the house seems to have brought a great deal of comfort to him. Some of Lamb's fondest childhood memories were of time spent with Mrs. Field, his maternal grandmother, who was for many years a servant to the Plummer family, who owned a large country house called Blakesware, near Widford, Hertfordshire. After the death of Mrs. Plummer, Lamb's grandmother was in sole charge of the large home and, as Mr. Plummer was often absent, Charles had free rein of the place during his visits. A picture of these visits can be glimpsed in the Elia essay Blakesmoor in H—shire. "Why, every plank and panel of that house for me had magic in it. The tapestried [sic] bed-rooms – tapestry so much better than painting – not adorning merely, but peopling the wainscots – at which childhood ever and anon would steal a look, shifting its coverlid (replaced as quickly) to exercise its tender courage in a momentary eye-encounter with those stern bright visages, staring reciprocally – all Ovid on the walls, in colours vivider than his descriptions.” Little is known about Charles's life before the age of seven. We know that Mary taught him to read at a very early age and he read voraciously. It is believed that he suffered from smallpox during his early years which forced him into a long period of convalescence. After this period of recovery Lamb began to take lessons from Mrs. Reynolds, a woman who lived in the Temple and is believed to have been the former wife of a lawyer. Mrs. Reynolds must have been a sympathetic schoolmistress because Lamb maintained a relationship with her throughout his life and she is known to have attended dinner parties held by Mary and Charles in the 1820s. E.V. Lucas suggests that sometime in 1781 Charles left Mrs. Reynolds and began to study at the Academy of William Bird. His time with William Bird did not last long, however, because by October 1782 Lamb was enrolled in Christ's Hospital, a charity boarding school chartered by King Edward VI in 1552. Christ's Hospital was a traditional English boarding school; bleak and full of violence. The headmaster, Mr. Boyer, has become famous for his teaching in Latin and Greek, but also for his brutality. A thorough record of Christ's Hospital in Several essays by Lamb as well as the Autobiography of Leigh Hunt and the Biographia Literaria of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, with whom Charles developed a friendship that would last for their entire lives. Despite the brutality Lamb got along well at Christ's Hospital, due in part, perhaps, to the fact that his home was not far distant thus enabling him, unlike many other boys, to return often to the safety of home. Years later, in his essay "Christ’s Hospital Five and Thirty Years Ago," Lamb described these events, speaking of himself in the third person as "L.” “I remember L. at school; and can well recollect that he had some peculiar advantages, which I and other of his schoolfellows had not. His friends lived in town, and were near at hand; and he had the privilege of going to see them, almost as often as he wished, through some invidious distinction, which was denied to us.” Christ's Hospital was a typical English boarding school and many students later wrote of the terrible violence they suffered there. The upper master of the school from 1778 to 1799 was Reverend James Boyer, a man renowned for his unpredictable and capricious temper. In one famous story Boyer was said to have knocked one of Leigh Hunt's teeth out by throwing a copy of Homer at him from across the room. Lamb seemed to have escaped much of this brutality, in part because of his amiable personality and in part because Samuel Salt, his father's employer and Lamb's sponsor at the school was one of the institute's Governors. Charles Lamb suffered from a stutter and this "an inconquerable impediment" in his speech deprived him of Grecian status at Christ's Hospital and thus disqualifying him for a clerical career. While Coleridge and other scholarly boys were able to go on to Cambridge, Lamb left school at fourteen and was forced to find a more prosaic career. For a short time he worked in the office of Joseph Paice, a London merchant and then, for 23 weeks, until 8 February 1792, held a small post in the Examiner's Office of the South Sea House. Its subsequent downfall in a pyramid scheme after Lamb left would be contrasted to the company's prosperity in the first Elia essay. On 5 April 1792 he went to work in the Accountant's Office for British East India Company, the death of his father's employer having ruined the family's fortunes.Charles would continue to work there for 25 years, until his retirement with pension. In 1792 while tending to his grandmother, Mary Field, in Hertfordshire, Charles Lamb fell in love with a young woman named Ann Simmons. Although no epistolary record exists of the relationship between the two, Lamb seems to have spent years wooing Miss Simmons. The record of the love exists in several accounts of Lamb's writing. Rosamund Gray is a story of a young man named Allen Clare who loves Rosamund Gray but their relationship comes to nothing because of the sudden death of Miss Gray. Miss Simmons also appears in several Elia essays under the name "Alice M." The essays "Dream Children," "New Year's Eve," and several others, speak of the many years that Lamb spent pursuing his love that ultimately failed. Miss Simmons eventually went on to marry a silversmith by the name of Bartram and Lamb called the failure of the affair his 'great disappointment. Family tragedy Charles and his sister Mary both suffered periods of mental illness. Charles spent six weeks in a psychiatric hospital during 1795. He was, however, already making his name as a poet. On 22 September 1796, a terrible event occurred: Mary, "worn down to a state of extreme nervous misery by attention to needlework by day and to her mother at night," was seized with acute mania and stabbed her mother to the heart with a table knife. Although there was no legal status of 'insanity' at the time, a jury returned a verdict of 'Lunacy' and therefore freed her from guilt of willful murder. With the help of friends Lamb succeeded in obtaining his sister's release from what would otherwise have been lifelong imprisonment, on the condition that he take personal responsibility for her safekeeping. Lamb used a large part of his relatively meagre income to keep his beloved sister in a private 'madhouse' in Islington called Fisher House. The 1799 death of John Lamb was something of a relief to Charles because his father had been mentally incapacitated for a number of years since suffering a stroke. The death of his father also meant that Mary could come to live again with him in Pentonville, and in 1800 they set up a shared home at Mitre Court Buildings in the Temple, where they lived until 1809. Despite Lamb's bouts of melancholia and alcoholism, both he and his sister enjoyed an active and rich social life. Their London quarters became a kind of weekly salon for many of the most outstanding theatrical and literary figures of the day. Charles Lamb, having been to school with Samuel Coleridge, counted Coleridge as perhaps his closest, and certainly his oldest, friend. On his deathbed, Coleridge had a mourning ring sent to Lamb and his sister. Fortuitously, Lamb's first publication was in 1796, when four sonnets by "Mr. Charles Lamb of the India House" appeared in Coleridge's Poems on Various Subjects. In 1797 he contributed additional blank verse to the second edition, and met the Wordsworths, William and Dorothy, on his short summer holiday with Coleridge at Nether Stowey, thereby also striking up a lifelong friendship with William. In London, Lamb became familiar with a group of young writers who favoured political reform, including Percy Bysshe Shelley, William Hazlitt, and Leigh Hunt. Lamb continued to clerk for the East India Company and doubled as a writer in various genres, his tragedy, John Woodvil, being published in 1802. His farce, Mr H, was performed at Drury Lane in 1807, where it was roundly booed. In the same year, Tales from Shakespeare (Charles handled the tragedies; his sister Mary, the comedies) was published, and became a best seller for William Godwin's "Children's Library." In 1819, at age 44, Lamb, who, because of family commitments, had never married, fell in love with an actress, Fanny Kelly, of Covent Garden, and proposed marriage. She refused him, and he died a bachelor. His collected essays, under the title Essays of Elia, were published in 1823 ("Elia" being the pen name Lamb used as a contributor to the London Magazine). A further collection was published ten years or so later, shortly before Lamb's death. He died of a streptococcal infection, erysipelas, contracted from a minor graze on his face sustained after slipping in the street, on 27 December 1834, just a few months after Coleridge. He was 59. From 1833 till their deaths Charles and Mary lived at Bay Cottage, Church Street, Edmonton north of London (now part of the London Borough of Enfield. Lamb is buried in All Saints' Churchyard, Edmonton. His sister, who was ten years his senior, survived him for more than a dozen years. She is buried beside him. Work Lamb's first publication was the inclusion of four sonnets in the Coleridge's Poems on Various Subjects published in 1796 by Joseph Cottle. The sonnets were significantly influenced by the poems of Burns and the sonnets of William Bowles, a largely forgotten poet of the late 18th century. His poems garnered little attention and are seldom read today. Lamb's contributions to the second edition of the Poems showed significant growth as a poet. These poems included The Tomb of Douglas and A Vision of Repentance. Because of a temporary fall-out with Coleridge, Lamb's poems were to be excluded in the third edition of the Poems. As it turned out, a third edition never emerged and instead Coleridge's next publication was the monumentally influential Lyrical Ballads co-published with Wordsworth. Lamb, on the other hand, published a book entitled Blank Verse with Charles Lloyd, the mentally unstable son of the founder of Lloyd's Bank. Lamb's most famous poem was written at this time entitled The Old Familiar Faces. Like most of Lamb's poems it is particularly sentimental but it is still remembered and widely read, often included in Poetic Collections. Of particular interest to Lambarians is the opening verse of the original version of The Old Familiar Faces which is concerned with Lamb's mother. It was a verse that Lamb chose to remove from the edition of his Collected Work published in 1818. I had a mother, but she died, and left me, Died prematurely in a day of horrors - All, all are gone, the old familiar faces. From a fairly young age Lamb desired to be a poet but never gained the success that he had hoped. Lamb lived under the poetic shadow of his friend Coleridge. In the final years of the 18th century Lamb began to work on prose with the novella entitled Rosamund Gray, a story of a young girl who was thought to be inspired by Ann Simmonds, with whom Charles Lamb was thought to be in love. Although the story is not particularly successful as a narrative because of Lamb's poor sense of plot, it was well thought of by Lamb's contemporaries and led Shelley to observe “what a lovely thing is Rosamund Gray! How much knowledge of the sweetest part of our nature in it!" (Quoted in Barnett, page 50) n the first years of the 19th century Lamb began his fruitful literary cooperation with his sister Mary. Together they wrote at least three books for William Godwin’s Juvenile Library. The most successful of these was of course Tales From Shakespeare which ran through two editions for Godwin and has now been published dozens of times in countless editions, many of them illustrated. Lamb also contributed a footnote to Shakespearean studies at this time with his essay "On the Tragedies of Shakespeare," in which he argues that Shakespeare should be read rather than performed in order to gain the proper effect of his dramatic genius. Beside contributing to Shakespeare studies with his book Tales From Shakespeare, Lamb also contributed to the popularization of Shakespeare's contemporaries with his book Specimens of the English Dramatic Poets Who Lived About the Time of Shakespeare. Although he did not write his first Elia essay until 1820, Lamb’s gradual perfection of the essay form for which he eventually became famous began as early 1802 in a series of open letters to Leigh Hunt’s Reflector. The most famous of these is called "The Londoner" in which Lamb famously derides the contemporary fascination with nature and the countryside. Legacy Anne Fadiman notes regretfully that Lamb is not widely read in modern times: "I do not understand why so few other readers are clamoring for his company... [he] is kept alive largely through the tenuous resuscitations of university English departments." Lamb was honoured by The Latymer School, a grammar school in Edmonton, a suburb of London where he lived for a time; it has six houses, one of which, "Lamb", is named after Charles. Selected works * Blank Verse, poetry, 1798 * A Tale of Rosamund Gray, and old blind Margaret, 1798 * John Woodvil, poetic drama, 1802 * Tales from Shakespeare, 1807 * The Adventures of Ulysses, 1808 * Specimens of English Dramatic poets who lived about the time of Shakespeare, 1808 * On the Tragedies of Shakespeare, 1811 * Witches and Other Night Fears, 1821 * The Pawnbroker's Daughter, 1825 * Eliana, 1867 * Essays of Elia, 1823 * The Last Essays of Elia, 1833 References Wikipedia – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Lamb

Archibald Lampman FRSC (17 November 1861– 10 February 1899) was a Canadian poet. “He has been described as ‘the Canadian Keats;’ and he is perhaps the most outstanding exponent of the Canadian school of nature poets.” The Canadian Encyclopedia says that he is "generally considered the finest of Canada’s late 19th-century poets in English.” Lampman is classed as one of Canada’s Confederation Poets, a group which also includes Charles G.D. Roberts, Bliss Carman, and Duncan Campbell Scott. Life Archibald Lampman was born at Morpeth, Ontario, a village near Chatham, the son of Archibald Lampman, an Anglican clergyman. “The Morpeth that Lampman knew was a small town set in the rolling farm country of what is now western Ontario, not far from the shores of Lake Erie. The little red church just east of the town, on the Talbot Road, was his father’s charge.” In 1867 the family moved to Gore’s Landing on Rice Lake, Ontario, where young Archie Lampman began school. In 1868 he contracted rheumatic fever, which left him lame for some years and with a permanently weakened heart. Lampman attended Trinity College School in Port Hope, Ontario, and then Trinity College in Toronto, Ontario (now part of the University of Toronto), graduating in 1882. While at university, he published early poems in Acta Victoriana, the literary journal of Victoria College. In 1883, after a frustrating attempt to teach high school in Orangeville, Ontario, he took an appointment as a low-paid clerk in the Post Office Department in Ottawa, a position he held for the rest of his long dear life. Lampman “was slight of form and of middle height. He was quiet and undemonstrative in manner, but had a fascinating personality. Sincerity and high ideals characterized his life and work.” On Sep. 3, 1887, Lampman married 20-year-old Maude Emma Playter. "They had a daughter, Natalie Charlotte, born in 1892. Arnold Gesner, born May 1894, was the first boy, but he died in August. A third child, Archibald Otto, was born in 1898." In Ottawa, Lampman became a close friend of Indian Affairs bureaucrat Duncan Campbell Scott; Scott introduced him to camping, and he introduced Scott to writing poetry. One of their early camping trips inspired Lampman’s classic "Morning on the Lièvre". Lampman also met and befriended poet William Wilfred Campbell. Lampman, Campbell, and Scott together wrote a literary column, “At the Mermaid Inn,” for the Toronto Globe from February 1892 until July 1893. (The name was a reference to the Elizabethan-era Mermaid Tavern.) As Lampman wrote to a friend: Campbell is deplorably poor.... Partly in order to help his pockets a little Mr. Scott and I decided to see if we could get the Toronto “Globe” to give us space for a couple of columns of paragraphs & short articles, at whatever pay we could get for them. They agreed to it; and Campbell, Scott and I have been carrying on the thing for several weeks now. “In the last years of his short life there is evidence of a spiritual malaise which was compounded by the death of an infant son [Arnold, commemorated in the poem “White Pansies”] and his own deteriorating health." Lampman died in Ottawa at the age of 37 due to a weak heart, an after-effect of his childhood rheumatic fever. He is buried, fittingly, at Beechwood Cemetery, in Ottawa, a site he wrote about in the poem “In Beechwood Cemetery” (which is inscribed at the cemetery’s entranceway). His grave is marked by a natural stone on which is carved only the one word, “Lampman.”. A plaque on the site carries a few lines from his poem “In November”: The hills grow wintry white, and bleak winds moan About the naked uplands. I alone Am neither sad, nor shelterless, nor gray Wrapped round with thought, content to watch and dream. Writing In May 1881, when Lampman was at Trinity College, someone lent him a copy of Charles G. D. Roberts’s recently published first book, Orion and Other Poems. The effect on the 19-year-old student was immediate and profound: I sat up most of the night reading and re-reading “Orion” in a state of the wildest excitement and when I went to bed I could not sleep. It seemed to me a wonderful thing that such work could be done by a Canadian, by a young man, one of ourselves. It was like a voice from some new paradise of art, calling to us to be up and doing. A little after sunrise I got up and went out into the college grounds... everything was transfigured for me beyond description, bathed in an old world radiance of beauty; the magic of the lines was sounding in my ears, those divine verses, as they seemed to me, with their Tennyson-like richness and strange earth-loving Greekish flavour. I have never forgotten that morning, and its influence has always remained with me. Lampman sent Roberts a fan letter, which "initiated a correspondence between the two young men, but they probably did not meet until after Roberts moved to Toronto in late September 1883 to become the editor of Goldwin Smith’s The Week.” Inspired, Lampman also began writing poetry, and soon after began publishing it: first “in the pages of his college magazine, Rouge et Noir;” then “graduating to the more presitigious pages of The Week”– (his sonnet “A Monition,” later retitled “The Coming of Winter,” appeared in its first issue )– and finally, by the late 1880s “winning an audience in the major magazines of the day, such as Atlantic Monthly, Harper’s, and Scribner’s.” Lampman published mainly nature poetry in the current late-Romantic style. “The prime literary antecedents of Lampman lie in the work of the English poets Keats, Wordsworth, and Arnold,” says the Gale Encyclopedia of Biography, “but he also brought new and distinctively Canadian elements to the tradition. Lampman, like others of his school, relied on the Canadian landscape to provide him with much of the imagery, stimulus, and philosophy which characterize his work.... Acutely observant in his method, Lampman created out of the minutiae of nature careful compositions of color, sound, and subtle movement. Evocatively rich, his poems are frequently sustained by a mood of revery and withdrawal, while their themes are those of beauty, wisdom, and reassurance, which the poet discovered in his contemplation of the changing seasons and the harmony of the countryside.” The Canadian Encyclopedia calls his poems “for the most part close-packed melancholy meditations on natural objects, emphasizing the calm of country life in contrast to the restlessness of city living. Limited in range, they are nonetheless remarkable for descriptive precision and emotional restraint. Although characterized by a skilful control of rhythm and sound, they tend to display a sameness of thought.” “Lampman wrote more than 300 poems in this last period of his life, although scarcely half of these were published prior to his death. For single poems or groups of poems he found outlets in the literary magazines of the day: in Canada, chiefly the Week; in the United States, Scribner’s Magazine, The Youth’s Companion, the Independent, the Atlantic Monthly, and Harper’s Magazine. In 1888, with the help of a legacy left to his wife, he published Among the millet and other poems," his first book, at his own expense. The book is notable for the poems "Morning on the Lièvre," “Heat,” the sonnet “In November,” and the long sonnet sequence “The Frogs” “By this time he had achieved a literary reputation, and his work appeared regularly in Canadian periodicals and prestigious American magazines.... In 1895 Lampman was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, and his second collection of poems, Lyrics of Earth, was brought out by a Boston publisher.” The book was not a success. “The sales of Lyrics of Earth were disappointing and the only critical notices were four brief though favourable reviews. In size, the volume is slighter than Among the Millet—twenty-nine poems in contrast to forty-eight—and in quality fails to surpass the earlier work.” (Lyrics does, though, contain some of Lampman’s most beautiful poems, such as “After Rain” and “The Sun Cup.”) “A third volume, Alcyone and other poems, in press at the time of his death” in 1899, showed Lampman starting to move in new directions, with the nature verses interspersed with philosophical poetry like “Voices of Earth” and “The Clearer Self” and poems of social criticism like “The City” and what may be his best-known poem, the dystopian vision of “The City of the End of Things.” “As a corollary to his preoccupation with nature,” notes the Gale Encyclopedia, "Lampman [had] developed a critical stance toward an emerging urban civilization and a social order against which he pitted his own idealism. He was an outspoken socialist, a feminist, and a social critic." Canadian critic Malcolm Ross wrote that “in poems like 'The City at the End of Things’ and 'Epitaph on a Rich Man’ Lampman seems to have a social and political insight absent in his fellows.” However, Lampman died before Alcyone appeared, and it "was held back by Scott (12 specimen copies were printed posthumously in Ottawa in 1899) in favour of a comprehensive memorial volume planned for 1900." The latter was a planned collected poems "which he was editing in the hope that its sale would provide Maud with some much-needed cash. Besides Alcyone, it included Among the Millet and Lyrics of Earth in their entirety, plus seventy-four sonnets Lampman had tried to publish separately, twenty-three miscellaneous poems and ballads, and two long narrative poems (“David and Abigail” and “The Story of an Affinity”)." Among the previously unpublished sonnets were some of Lampman’s finest work, including “Winter Uplands”, “The Railway Station,” and “A Sunset at Les Eboulements.” “Published by Morang & Company of Toronto in 1900," The Poems of Archibald Lampman "was a substantial tome—473 pages—and ran through several editions. Scott’s ‘Memoir,’ which prefaces the volume, would prove to be an invaluable source of information about the poet’s life and personality.” Scott published one further volume of Lampman’s poetry, At the Long Sault and Other Poems, in 1943– “and on this occasion, as on other occasions previously, he did not hesitate to make what he felt were improvements on the manuscript versions of the poems.” The book is remarkable mainly for its title poem, "At the Long Sault: May 1660," a dramatic retelling of the Battle of Long Sault, which belongs with the great Canadian historical poems. It was co-edited by E.K. Brown, who the same year published his own volume On Canadian Poetry: a book that was a major boost to Lampman’s reputation. Brown considered Lampman and Scott the top Confederation Poets, well ahead of Roberts and Carman, and his view came to predominate over the next few decades. Lampman never considered himself more than a minor poet, as he once confessed in a letter to a friend: “I am not a great poet and I never was. Greatness in poetry must proceed from greatness of character—from force, fearlessness, brightness. I have none of those qualities. I am, if anything, the very opposite, I am weak, I am a coward, I am a hypochondriac. I am a minor poet of a superior order, and that is all.” However, others’ opinion of his work has been higher than his own. Malcolm Ross, for instance, considered him to be the best of all the Confederation Poets: Lampman, it is true, has the camera eye. But Lampman is no mere photographer. With Scott (and more completely than Scott), he has, poetically, met the demands of his place and his time.... Like Roberts (and more intensively than Roberts), he searches for the idea.... Ideas are germinal for him, infecting the tissue of his thought.... Like the existentialist of our day, Lampman is not so much 'in search of himself’ as engaged strenuously in the creation of the self. Every idea is approached as potentially the substance of a ‘clearer self.’ Even landscape is made into a symbol of the deep, interior processes of the self, or is used... to induce a settling of the troubled surfaces of the mind and a miraculous transparency that opens into the depths. Recognition Lampman was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada in 1895. He was designated a Person of National Historic Significance in 1920. A literary prize, the Archibald Lampman Award, is awarded annually by Ottawa-area poetry magazine Arc in Lampman’s honour. Since 1999, the annual “Archibald Lampman Poetry Reading” has brought leading Canadian poets to Trinity College, Toronto, under the sponsorship of the John W. Graham Library and the Friends of the Library, Trinity College. His name is also carried on in the town of Lampman, Saskatchewan, a small community of approximately 730 people, situated near the City of Estevan. Canada Post issued a postage stamp in his honour on July 7, 1989. The stamp depicts Lampman’s portrait on a backdrop of nature. Canadian singer/songwriter Loreena McKennitt adapted Lampman’s poem “Snow” as a song, writing original music while keeping as the lyrics the poem verbatim. This adaptation appears on McKennitt’s album To Drive the Cold Winter Away (1987) and also in a different version on her EP, A Winter Garden: Five Songs for the Season (1995). Publications Poetry * Lampman, Archibald (1888). Among the Millett, and Other Poems. Ottawa, Ontario: J. Durie and son. * Lampman, Archibald (1895). Lyrics of Earth. Boston, Massachusetts: Copeland & Day. * Lampman, Archibald; Scott, Duncan Campbell (1896). “Two poems”. privately issued to their friends at Christmastide: not published. * Lampman, Archibald (1899). Alcyone and Other Poems. Ottawa, Ontario: Ogilvy. * Scott, Duncan Campbell, ed. (1900). The Poems of Archibald Lampman. Toronto, Ontario: Morang. * Scott, Duncan Campbell, ed. (1925). Lyrics of Earth: Sonnets and Ballads. Toronto, Ontario: Musson. * Scott, Duncan Campbell, ed. (1943). At the Long Sault and Other New Poems. Toronto, Ontario: Ryerson. * Scott, Duncan Campbell, ed. (1947). Selected Poems of Archibald Lampman. Toronto, Ontario: Ryerson. * Coulby Whitridge, Margaret, ed. (1975). Lampman’s Kate: Late Love Poems of Archibald Lampman. Ottawa, Ontario: Borealis. ISBN 978-0-9195-9436-4. * Coulby Whitridge, Margaret, ed. (1976). Lampman’s Sonnets: The Complete Sonnets of Archibald Lampman. Ottawa, Ontario: Borealis. ISBN 978-0-919594-50-0. * Bentley, D.M.R., ed. (1986). The Story of an Affinity. London, Ontario: Canadian Poetry Press. ISBN 978-0-921243-00-7. * Gnarowski, Michael, ed. (1990). Selected Poetry of Archibald Lampman. Ottawa, Ontario: Tecumseh. ISBN 978-0-919662-15-5. Prose * Bourinot, Arthur S., ed. (1956). Archibald Lampman’s letters to Edward William Thomson (1890-1898). Ottawa, Ontario: Arthur S. Bourinot Publisher. * Davies, Barrie, ed. (1975). Archibald Lampman: Selected Prose. Ottawa, Ontario: Tecumseh. ISBN 978-0-9196-6254-4. * Davies, Barrie, ed. (1979). At the Mermaid Inn: Wilfred Campbell, Archibald Lampman, Duncan Campbell Scott in the Globe 1892–93. Toronto, Ontario: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-2299-5. * Lynn, Helen, ed. (1980). An annotated edition of the correspondence between Archibald Lampman and Edward William Thomson, 1890-1898. Ottawa, Ontario: Tecumseh. ISBN 978-0-919662-77-3. * Bentley, D.M.R., ed. (1996). The Essays and Reviews of Archibald Lampman. London, Ontario: Canadian Poetry Press. * Bentley, D.M.R., ed. (1999). The Fairy Tales of Archibald Lampman. London, Ontario: Canadian Poetry Press. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archibald_Lampman

Alexandre is a musician, poet, and philosopher with a deep interest in the mystical, magickal, and occult. While he has been playing music ever since he was 3 years old, his interest in mysticism and poetry came about from the study of philosophy. Beginning in college with the standard western philosophers such as Plato, Kant, Descartes, and Nietzsche, he realized that there was still much more in the realm of wisdom to be explored. Reading about Zen, Taoism, and Cabala instilled an appreciation of simple, poetic verse as a way of communicating wisdom, and led him to the study of the magickal system of Aleister Crowley, known as Thelema, from where he draws much of his inspiration.

Rosanna Eleanor Leprohon (January 12, 1829– September 20, 1879), born Rosanna Eleanor Mullins, was a Canadian writer and poet. She was “one of the first English-Canadian writers to depict French Canada in a way that earned the praise of, and resulted in her novels being read by, both anglophone and francophone Canadians.”

I write poetry when I'm in a bad mood, or when I'm depressed. Which is often. I play clarinet, cello, and guitar, and I'm a singer. Sprint cars and rock stars. Classic rock, heavy metal and pop punk fan. Journey and Bon Jovi are life. Green Day saved me. Working on poetry now. Will post when completed.

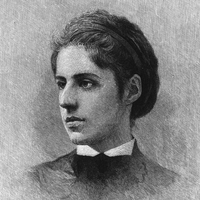

Emma Lazarus (July 22, 1849– November 19, 1887) was an American poet born in New York City. She is best known for “The New Colossus”, a sonnet written in 1883; its lines appear inscribed on a bronze plaque in the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty installed in 1903, a decade and a half after Lazarus’s death. Lazarus was born into a large Sephardic-Ashkenazi Jewish family, the fourth of seven children of Moses Lazarus and Esther Nathan, The Lazarus family was from Germany, and the Nathan family was originally from Portugal and resident in New York long before the American Revolution.

Walter Savage Landor (30 January 1775 – 17 September 1864) was an English writer and poet. His best known works were the prose Imaginary Conversations, and the poem Rose Aylmer, but the critical acclaim he received from contemporary poets and reviewers was not matched by public popularity. As remarkable as his work was, it was equalled by his rumbustious character and lively temperament.

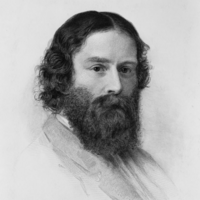

James Russell Lowell (February 22, 1819– August 12, 1891) was an American Romantic poet, critic, editor, and diplomat. He is associated with the Fireside Poets, a group of New England writers who were among the first American poets who rivaled the popularity of British poets. These poets usually used conventional forms and meters in their poetry, making them suitable for families entertaining at their fireside. Lowell graduated from Harvard College in 1838, despite his reputation as a troublemaker, and went on to earn a law degree from Harvard Law School. He published his first collection of poetry in 1841 and married Maria White in 1844. He and his wife had several children, though only one survived past childhood. The couple soon became involved in the movement to abolish slavery, with Lowell using poetry to express his anti-slavery views and taking a job in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, as the editor of an abolitionist newspaper. After moving back to Cambridge, Lowell was one of the founders of a journal called The Pioneer, which lasted only three issues. He gained notoriety in 1848 with the publication of A Fable for Critics, a book-length poem satirizing contemporary critics and poets. The same year, he published The Biglow Papers, which increased his fame.

I was born in Crescent City, California, but was not there for long. I moved to Libby, Montana when I was only two, and lived there for the next 7 years of my life. I loved Libby, knew the streets as well as any 8 or 9 year old could, so as expected, I cried when my family of six moved to the small town of Troy just 18 miles away. Slowly I learned to love Troy just as much, and soon had friends and was even enjoying my time in my new school! One very short year of fun and laughter went by and we were moving again. I spent a month up in Eureka with my sister and two brothers, while our mom went off to the city of Bozeman, Montana, almost 400 miles south to visit family. My other two siblings moved back to Spokane to be with their father, and my sister decided to stay in Eureka when we moved. The rest of us happily lived and camped in the foothills of the Hyalite Canyon in Bozeman for the next two summer months. My mom would take my two brothers and I to the "Bozeman Beach" almost every day she wasn't working, and we would play in the sand and swim in the pond and have the time of our lives. One day, I saw an alligator made of sand, and wanted to make one myself, so I asked the man who had made it to help me. He and my mom got to talking and he invited us all over to dinner. When he learned of our situation, he offered to share his home with us! we now had a real roof over our heads. My sister eventually moved down to Bozeman with us, but the other two decided to stay in Washington. There was a normal life then, filled with school, friends, pets, singing and dancing, heartbreaks and love, happiness, and most importantly, family. My incredible mom has made this house a home, and openly welcomes us to come and go, all the while holding us together with her love and devotion to us. My very first poem was written for her, and though it is lost to time, I have been writing poetry ever since.

Clive Staples Lewis (29 November 1898 – 22 November 1963), commonly called C. S. Lewis and known to his friends and family as “Jack”, was a novelist, poet, academic, medievalist, literary critic, essayist, lay theologian, and Christian apologist. Born in Belfast, Ireland, he held academic positions at both Oxford University (Magdalen College), 1925–1954, and Cambridge University (Magdalene College), 1954–1963. He is best known both for his fictional work, especially The Screwtape Letters, The Chronicles of Narnia, and The Space Trilogy, and for his non-fiction Christian apologetics, such as Mere Christianity, Miracles, and The Problem of Pain. Lewis and fellow novelist J. R. R. Tolkien were close friends. Both authors served on the English faculty at Oxford University, and both were active in the informal Oxford literary group known as the “Inklings”. According to his memoir Surprised by Joy, Lewis had been baptized in the Church of Ireland (part of the Anglican Communion) at birth, but fell away from his faith during his adolescence. Owing to the influence of Tolkien and other friends, at the age of 32 Lewis returned to the Anglican Communion, becoming “a very ordinary layman of the Church of England”. His faith had a profound effect on his work, and his wartime radio broadcasts on the subject of Christianity brought him wide acclaim.

The world either goes too fast or too slow. Things are either too good to be true or too awful we want them to be nightmares. Sometimes words aren't enough to describe what we feel inside, but still we try, try to slow down the world fast forward it and we try to describe what we feel and who we are. And we try to make sense of things and find explanation for the things that are too good or too awful, so that hopefully we have peace at mind.

Letitia Elizabeth Landon (14 August 1802– 15 October 1838), English poet and novelist, better known by her initials L. E. L. Born in Chelsea, London to John Landon and Catherine Jane Bishop. A precocious child, Landon learned to read as a toddler. Her reputation, while high in the 19th century, fell during most of the 20th as literary fashions changed and Landon’s poetry was perceived as overly simple and sentimental. In recent years, however, scholars and critics have increasingly studied her work, beginning with Germaine Greer in the 1970s.

Sidney Clopton Lanier (February 3, 1842– September 7, 1881) was an American musician, poet and author. He served in the Confederate army, worked on a blockade running ship for which he was imprisoned (resulting in his catching tuberculosis), taught, worked at a hotel where he gave musical performances, was a church organist, and worked as a lawyer. As a poet he used dialects. He became a flautist and sold poems to publications. He eventually became a university professor and is known for his adaptation of musical meter to poetry. Many schools, other structures and two lakes are named for him. Biography Sidney Clopton Lanier was born February 3, 1842, in Macon, Georgia, to parents Robert Sampson Lanier and Mary Jane Anderson; he was mostly of English ancestry. His distant French Huguenot ancestors immigrated to England in the 16th century, fleeing religious persecution. He began playing the flute at an early age, and his love of that musical instrument continued throughout his life. He attended Oglethorpe University, which at the time was near Milledgeville, Georgia, and he was a member of the Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity. He graduated first in his class shortly before the outbreak of the American Civil War. He fought in the American Civil War (1861–65), primarily in the tidewater region of Virginia, where he served in the Confederate signal corps. Later, he and his brother Clifford served as pilots aboard English blockade runners. On one of these voyages, his ship was boarded. Refusing to take the advice of the British officers on board to don one of their uniforms and pretend to be one of them, he was captured. He was incarcerated in a military prison at Point Lookout in Maryland, where he contracted tuberculosis (generally known as “consumption” at the time). He suffered greatly from this disease, then incurable and usually fatal, for the rest of his life. Shortly after the war, he taught school briefly, then moved to Montgomery, Alabama, where he worked as a desk clerk at The Exchange Hotel and also performed as a musician. He was the regular organist at The First Presbyterian Church in nearby Prattville. He wrote his only novel, Tiger Lilies (1867) while in Alabama. This novel was partly autobiographical, describing a stay in 1860 at his grandfather’s Montvale Springs resort hotel near Knoxville, Tennessee. In 1867, he moved to Prattville, at that time a small town just north of Montgomery, where he taught and served as principal of a school. He married Mary Day of Macon in 1867 and moved back to his hometown, where he began working in his father’s law office. After taking and passing the Georgia bar, Lanier practiced as a lawyer for several years. During this period he wrote a number of poems, using the “cracker” and “negro” dialects of his day, about poor white and black farmers in the Reconstruction South. He traveled extensively through southern and eastern portions of the United States in search of a cure for his tuberculosis. While on one such journey in Texas, he rediscovered his native and untutored talent for the flute and decided to travel to the northeast in hopes of finding employment as a musician in an orchestra. Unable to find work in New York City, Philadelphia, or Boston, he signed on to play flute for the Peabody Orchestra in Baltimore, Maryland, shortly after its organization. He taught himself musical notation and quickly rose to the position of first flautist. He was famous in his day for his performances of a personal composition for the flute called “Black Birds”, which mimics the song of that species. In an effort to support Mary and their three sons, he also wrote poetry for magazines. His most famous poems were “Corn” (1875), “The Symphony” (1875), “Centennial Meditation” (1876), “The Song of the Chattahoochee” (1877), “The Marshes of Glynn”, (1878) and “Sunrise” (1881). The latter two poems are generally considered his greatest works. They are part of an unfinished set of lyrical nature poems known as the “Hymns of the Marshes”, which describe the vast, open salt marshes of Glynn County on the coast of Georgia. (The longest bridge in Georgia is in Glynn County and is named for Lanier.) Later life Late in his life, he became a student, lecturer, and, finally, a faculty member at the Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, specializing in the works of the English novelists, Shakespeare, the Elizabethan sonneteers, Chaucer, and the Old English poets. He published a series of lectures entitled The English Novel (published posthumously in 1883) and a book entitled The Science of English Verse (1880), in which he developed a novel theory exploring the connections between musical notation and meter in poetry. Lanier finally succumbed to complications caused by his tuberculosis on September 7, 1881, while convalescing with his family near Lynn, North Carolina. He was 39. Lanier is buried in Green Mount Cemetery in Baltimore. Writing style and literary theory With his theory connecting musical notation with poetic meter, and also being described as a deft metrical technical, in his own words ‘daring with his poem ’Special Pleading’ to give myself such freedom as I desired, in my own style’ and also by developing a unique style of poetry written in logaoedic dactyls, which was strongly influenced by the works of his beloved Anglo-Saxon poets. He wrote several of his greatest poems in this meter, including “Revenge of Hamish” (1878), “The Marshes of Glynn” and “Sunrise”. In Lanier’s hands, the logaoedic dactylic meter led to a free-form, almost prose-like style of poetry that was greatly admired by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Bayard Taylor, Charlotte Cushman, and other leading poets and critics of the day. A similar poetical meter was independently developed by Gerard Manley Hopkins at about the same time (there is no evidence that they knew each other or that either of them had read any of the other’s works). Lanier also published essays on other literary and musical topics and a notable series of four redactions of literary works about knightly combat and chivalry in modernized language more appealing to the boys of his day: The Boy’s Froissart (1878), a retelling of Jean Froissart’s Froissart’s Chronicles, which tell of adventure, battle and custom in medieval England, France and Spain The Boy’s King Arthur (1880), based on Sir Thomas Malory’s compilation of the legends of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table The Boy’s Mabinogion (1881), based on the early Welsh legends of King Arthur, as retold in the Red Book of Hergest. The Boy’s Percy (published posthumously in 1882), consisting of old ballads of war, adventure and love based on Bishop Thomas Percy’s Reliques of Ancient English Poetry. He also wrote two travelogues that were widely read at the time, entitled Florida: Its Scenery, Climate and History (1875) and Sketches of India (1876) (although he never visited India). Legacy and honors The Sidney Lanier Cottage in Macon, Georgia is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The square, stone Monument to Poets of Georgia, located between 7th & 8th St. in Augusta, lists Lanier as one of Georgia’s four great poets, all of whom saw Confederate service. The southeastern side bears this inscription: "To Sidney Lanier 1842–1880. The catholic man who hath nightly won God out of knowledge and good out of infinite pain and sight out of Blindness and Purity out of stain." The other poets on the monument are James Ryder Randall, Fr. Abram Ryan, and Paul Hayne. Baltimore honored Lanier with a large and elaborate bronze and granite sculptural monument, created by Hans K. Schuler and located on the campus of the Johns Hopkins University. In addition to the monument at Johns Hopkins, Lanier was also later memorialized on the campus of Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. Upon the construction of the iconic Duke Chapel between 1930 and 1935 on the university’s West Campus, a statue of Lanier was included alongside two fellow prominent Southerners, Thomas Jefferson and Robert E. Lee. This statue, which appears to show a Lanier older than the 39 years he actually lived, is situated on the right side of the portico leading into the Chapel narthex. It is prominently featured on the cover of the 2010 autobiographical memoir Hannah’s Child, by Stanley Hauerwas, a Methodist theologian teaching at Duke Divinity School. Lanier’s poem “The Marshes of Glynn” is the inspiration for a cantata by the same name that was created by the modern English composer Andrew Downes to celebrate the Royal Opening of the Adrian Boult Hall in Birmingham, England, in 1986. Piers Anthony used Lanier, his life, and his poetry in his science-fiction novel Macroscope (1969). He quotes from “The Marshes of Glynn” and other references appear throughout the novel. Several entities have been named for Sidney Lanier: Inhabited places Lanier Heights Neighborhood, Washington, D.C. Lanier County, Georgia Indirectly, USS Lanier, which was named for the county. Bodies of water Lake Lanier, operated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers northeast of Atlanta, Georgia (The lake was created by the damming of the Chattahoochee River, a river that was the subject of one of Lanier’s poems.) Lake Lanier in Tryon, North Carolina Schools Sidney Lanier High School in Montgomery, Alabama Sidney Lanier School in Gainesville, Florida Lanier University short-lived university, first Baptist, then owned by the Ku Klux Klan, in Atlanta, Georgia The Sidney Lanier Building (previously Sidney Lanier Elementary School) on the campus of Glynn Academy, in Brunswick, Georgia Lanier Middle School in Buford, Georgia Lanier Elementary School in Gainesville, Georgia Sidney Lanier Elementary School in Tulsa, Oklahoma Sidney Lanier High School in Austin, Texas Sidney Lanier Expressive Arts Vanguard Elementary School in Dallas, Texas Lanier Middle School in Houston, Texas Lanier High School in San Antonio, Texas Lanier Middle School in Fairfax, Virginia Sidney Lanier Elementary School in Tampa, Florida Lanier Technical College in Oakwood, Georgia Other Sidney Lanier Cottage, the birthplace of Lanier, in Macon, Georgia Sidney Lanier Bridge over the South Brunswick River in Brunswick, Georgia Lanier’s Oak in Brunswick, Georgia The Lanier Library, Tryon, North Carolina. Lanier’s widow, Mary, donated two of his volumes of poetry to begin the collection when the library was established in 1890. Sidney Lanier Camp, Eliot, Maine. Sidney Lanier Boulevard in Duluth, GA References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sidney_Lanier

Amy Judith Levy (10 November 1861– 10 September 1889) was a British essayist, poet, and novelist best remembered for her literary gifts; her experience as the first Jewish woman at Cambridge University and as a pioneering woman student at Newnham College, Cambridge; her feminist positions; her friendships with others living what came later to be called a “new woman” life, some of whom were lesbians; and her relationships with both women and men in literary and politically activist circles in London during the 1880s. Biography Levy was born in Clapham, an affluent district of London, on November 10, 1861, to Lewis and Isobel Levy. She was the second of seven children born into a Jewish family with a “casual attitude toward religious observance” who sometimes attended a Reform synagogue in Upper Berkeley Street. As an adult, Levy continued to identify herself as Jewish and wrote for The Jewish Chronicle. Levy showed interest in literature from an early age. At 13, she wrote a criticism of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s feminist work Aurora Leigh; at 14, Levy’s first poem, “Ida Grey: A Story of Woman’s Sacrifice”, was published in the journal Pelican. Her family was supportive of women’s education and encouraged Amy’s literary interests; in 1876, she was sent to Brighton and Hove High School and later studied at Newnham College, Cambridge. Levy was the first Jewish student at Newnham when she arrived in 1879 but left before her final year without taking her exams. Her circle of friends included Clementina Black, Dollie Radford, Eleanor Marx (daughter of Karl Marx), and Olive Schreiner. While travelling in Florence in 1886, Levy met Vernon Lee, a fiction writer and literary theorist six years her senior, and fell in love with her. Both women would go on to write works with themes of sapphic love. Lee inspired Levy’s poem “To Vernon Lee.” Literary career The Romance of a Shop (1888), Levy’s first novel, is regarded as an early “New Woman” novel and depicts four sisters who experience the difficulties and opportunities afforded to women running a business in 1880s London, Levy wrote her second novel, Reuben Sachs (1888), to fill the literary need for “serious treatment... of the complex problem of Jewish life and Jewish character”, which she identified and discussed in her 1886 article “The Jew in Fiction.” Levy wrote stories, essays, and poems for popular or literary periodicals; the stories “Cohen of Trinity” and “Wise in Their Generation”, both published in Oscar Wilde’s magazine The Woman’s World, are among her most notable. In 1886, Levy began writing a series of essays on Jewish culture and literature for The Jewish Chronicle, including The Ghetto at Florence, The Jew in Fiction, Jewish Humour, and Jewish Children. Levy’s works of poetry, including the daring A Ballad of Religion and Marriage, reveal her feminist concerns. Xantippe and Other Verses (1881) includes “Xantippe”, a poem in the voice of Socrates’s wife; the volume A Minor Poet and Other Verse (1884) includes more dramatic monologues as well as lyric poems. Her final book of poems, A London Plane-Tree (1889), contains lyrics that are among the first to show the influence of French symbolism. Suicide Levy suffered from episodes of major depression from an early age. In her later years, her depression worsened in connection to her distress surrounding her romantic relationships and her awareness of her growing deafness. Two months away from her 28th birthday, she committed suicide at the residence of her parents... [at] Endsleigh Gardens by inhaling carbon monoxide. Oscar Wilde wrote an obituary for her in Women’s World in which he praised her gifts.

Denise Levertov (24 October 1923– 20 December 1997) was a British-born American poet. Levertov, who was educated at home, showed an enthusiasm for writing from an early age and studied ballet, art, piano and French as well as standard subjects. She wrote about the strangeness she felt growing up part Jewish, German, Welsh and English, but not fully belonging to any of these identities. She notes that it lent her a sense of being special rather than excluded: “I knew before I was ten that I was an artist-person and I had a destiny”.

Audre Lorde (born Audrey Geraldine Lorde, February 18, 1934 – November 17, 1992) was a Black American writer, feminist, womanist, lesbian, and civil rights activist. As a poet, she is best known for technical mastery and emotional expression, particularly in her poems expressing anger and outrage at civil and social injustices she observed throughout her life. Her poems and prose largely dealt with issues related to civil rights, feminism, and the exploration of black female identity. In relation to non-intersectional feminism in the United States, Lorde famously said, “Those of us who stand outside the circle of this society’s definition of acceptable women; those of us who have been forged in the crucibles of difference—those of us who are poor, who are lesbians, who are Black, who are older—know that survival is not an academic skill. It is learning how to take our differences and make them strengths. For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change. And this fact is only threatening to those women who still define the master’s house as their only source of support.”

#Americans #Blacks #Gays #Lesbian #Women

I'm a writer, free-thinker, designer and mother of three. I'm working on my first book, a memoir which I am aiming to finish in 2016. Being a creative spirit, I've found life to be rocky at times... It took me a long time to finally dedicate myself to 'my work' - one day I hope it will be paid work (!) but for now it is enough just to put it out there in the hope that I inspire others. http://goingtoseed.blogspot.com.au - My blog 'Going To Seed' where I explore all sorts of ideas and progressive thinking...