William Barnes (22 February 1801– 7 October 1886) was an English writer, poet, Church of England priest, and philologist. He wrote over 800 poems, some in Dorset dialect, and much other work, including a comprehensive English grammar quoting from more than 70 different languages. Barnes was born at Rushay in the parish of Bagber, Dorset, the son of a farmer. His formal education finished when he was 13 years old. Between 1818 and 1823 he worked in Dorchester, the county town, as a solicitor’s clerk, then moved to Mere in neighbouring Wiltshire and opened a school. During his time here he began writing poetry in the Dorset dialect, as well as studying several languages (Italian, Persian, German and French, in addition to Greek and Latin), playing musical instruments (violin, piano and flute) and practising wood-engraving. He married Julia Miles, the daughter of an exciseman from Dorchester, in 1827, then in 1835 moved back to the county town, where again he ran a school. The school was initially in Durngate Street, then was moved to South Street. A second move to another South Street site made the school a neighbour of an architect’s practice where Thomas Hardy was an apprentice. The architect, John Hicks, was interested in literature and the classics, and when disputes about grammar occurred in the practice, Hardy would visit Barnes next door for an authoritative opinion.

I started dabbling at age 13, and after a while, I was writing full poems, however, I only have poetry from when I was 16 and up. I am now 30, and I have found that it is so much easier to say things through poetry than it is to verbalize them. I draw inspiration for my poetry from writers, musicians, movies, daily interactions, my faith, and much more. As far as writers go, when I was younger I got introduced to Langston Hughes, and I have learned to take from his style of writing. I also enjoy some good old Shakespeare every once in a while. Most of my influence, however, comes from music; I draw my influence from genres that include but are not limited to, hip-hop, rock, and country. Another thing that really impacts my poetry are events that have taken place in my life. Movie characters and themes also have a chance to have their fair share of influence in my poetry. I am a spiritual person, so, beneath most of my poems stories, there is a spiritual undertone. People can create all sorts of art without having to fabricate who they are, and without compromising who they are as a person; it's being able to take from other peoples experiences and write about them, based on the writer's interpretation, that can set a writer apart from others. I write mainly Free Verse poetry, because to me poetry is a lot of self-expression, and if I were to follow the set guidelines of a certain type of poetry, I would then be forfeiting my creative license. Sometimes, however, I like to take from certain styles of poetry, especially when I am trying to convey a particular emotion, for example, I not only write Free Verse but, I have learned to take from styles, such as Blank Verse & Limericks. I have a friend who said this, "If there is one thing that I have learned about writing over the years it is that the best work comes from writing without the audience in mind." I find this quote to be accurate for not only my writing but for writing in general. Love y'all!

Robert Herrick (baptized 24 August 1591 – buried 15 October 1674) was a 17th-century English poet. The Victorian poet Swinburne described Herrick as the greatest song writer ever born of English race. It is certainly true that despite his use of classical allusions and names, his poems are easier for modern readers to understand than those of many of his contemporaries. The over-riding message of Herrick’s work is that life is short, the world is beautiful, love is splendid, and we must use the short time we have to make the most of it. This message can be seen clearly in To the Virgins, to make much of Time, To Daffodils, To Blossoms and Corinna going a-Maying, where the warmth and exuberance of what seems to have been a kindly and jovial personality comes over strongly. The opening stanza in one of his more famous poems, "To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time", is as follows: Gather ye rosebuds while ye may, Old Time is still a-flying; And this same flower that smiles today, Tomorrow will be dying.

#English #XVICentury #XVIICentury

Herman Melville (August 1, 1819– September 28, 1891) was an American novelist, short story writer, and poet of the American Renaissance period best known for Typee (1846), a romantic account of his experiences in Polynesian life, and his whaling novel Moby-Dick (1851). His work was almost forgotten during his last thirty years. His writing draws on his experience at sea as a common sailor, exploration of literature and philosophy, and engagement in the contradictions of American society in a period of rapid change. He developed a complex, baroque style: the vocabulary is rich and original, a strong sense of rhythm infuses the elaborate sentences, the imagery is often mystical or ironic, and the abundance of allusion extends to Scripture, myth, philosophy, literature, and the visual arts.

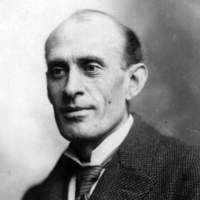

Franklin Pierce Adams (November 15, 1881 – March 23, 1960) was an American columnist, well known by his initials F.P.A., and wit, best known for his newspaper column, “The Conning Tower”, and his appearances as a regular panelist on radio’s Information Please. A prolific writer of light verse, he was a member of the Algonquin Round Table of the 1920s and 1930s. Adams was born Franklin Leopold Adams to Moses and Clara Schlossberg Adams in Chicago on November 15, 1881. He changed his middle name to “Pierce” when he had a Jewish confirmation ceremony at age 13. Adams graduated from the Armour Scientific Academy (now Illinois Institute of Technology) in 1899, attended the University of Michigan for one year and worked in insurance for three years.

I've been writing all my life, since I could read and hold a pen. Its only been in the last couple of years that friends and writing colleagues have encouraged me to submit work for publication. Slowly I've been finding success in getting work recognised in magazines and journals and at spoken word events. I'll post here as regularly as I can, posting poems that are new that I like or have achieved some success. I hope the writing engenders some understanding and encouragement #poetatheart

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936) was an English writer, philosopher, Christian apologist, and literary and art critic. He has been referred to as the "prince of paradox". Of his writing style, Time observed: "Whenever possible Chesterton made his points with popular sayings, proverbs, allegories—first carefully turning them inside out." Chesterton created the fictional priest-detective Father Brown, and wrote on apologetics. Even some of those who disagree with him have recognised the wide appeal of such works as Orthodoxy and The Everlasting Man. Chesterton routinely referred to himself as an "orthodox" Christian, and came to identify this position more and more with Catholicism, eventually converting to Roman Catholicism from high church Anglicanism. Biographers have identified him as a successor to such Victorian authors as Matthew Arnold, Thomas Carlyle, John Henry Newman and John Ruskin.

I have been a hopeless romantic since I was a young boy. I have always been drawn to relationships and the experience of love. The exhilaration and emotions that flood into and coarse through those that are in love is the most intoxicating feeling possible, at least in my opinion. As you read these poems, you are reading my story. I write about my thoughts, my feelings, and my experiences. Forgive me if my writings are not of your flavor as I never did read much poetry from others.

John Robinson Jeffers (January 10, 1887 – January 20, 1962) was an American poet, known for his work about the central California coast. Much of Jeffers' poetry was written in narrative and epic form, but he is also known for his shorter verse and is considered an icon of the environmental movement. Influential and highly regarded in some circles, despite or because of his philosophy of "inhumanism," Jeffers believed that transcending conflict required human concerns to be de-emphasized in favor of the boundless whole. This led him to oppose U.S. participation in World War II, a stand that was controversial at the time. Jeffers was born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania (now part of Pittsburgh), the son of a Presbyterian minister and biblical scholar, Reverend Dr. William Hamilton Jeffers, and Annie Robinson Tuttle. His brother was Hamilton Jeffers, who became a well-known astronomer, working at Lick Observatory. His family was supportive of his interest in poetry. He traveled through Europe during his youth and attended school in Switzerland. He was a child prodigy, interested in classics and Greek and Latin language and literature. At sixteen he entered Occidental College. At school, he was an avid outdoorsman, and active in the school's literary societies. After he graduated from Occidental, Jeffers went to the University of Southern California to study at first literature, and then medicine. He met Una Call Kuster in 1906; she was three years older than he was, a graduate student, and the wife of a Los Angeles attorney. In 1910 he enrolled as a forestry student at the University of Washington in Seattle, a course of study that he abandoned after less than one year, at which time he returned to Los Angeles. Sometime before this, he and Una had begun an affair that became a scandal, reaching the front page of the Los Angeles Times in 1912. After Una spent some time in Europe to quiet things down, the two were married in 1913, and moved to Carmel, California, where Jeffers constructed Tor House and Hawk Tower. The couple had a daughter who died a day after birth in 1914, and then twin sons (Donnan and Garth) in 1916. Una died of cancer in 1950. Jeffers died in 1962; an obituary can be found in the New York Times, January 22, 1962. Poetic career In the 1920s and 1930s, at the height of his popularity, Jeffers was famous for being a tough outdoorsman, living in relative solitude and writing of the difficulty and beauty of the wild. He spent most of his life in Carmel, California, in a granite house that he had built himself called "Tor House and Hawk Tower". Tor is a term for a craggy outcrop or lookout. Before Jeffers and Una purchased the land where Tor House would be built, they rented two cottages in Carmel, and enjoyed many afternoon walks and picnics at the "tors" near the site that would become Tor House. To build the first part of Tor House, a small, two story cottage, Jeffers hired a local builder, Michael Murphy. He worked with Murphy, and in this short, informal apprenticeship, he learned the art of stonemasonry. He continued adding on to Tor House throughout his life, writing in the mornings and working on the house in the afternoon. Many of his poems reflect the influence of stone and building on his life. He later built a large four-story stone tower on the site called Hawk Tower. While he had not visited Ireland at this point in his life, it is possible that Hawk Tower is based on Francis Joseph Bigger's 'Castle Séan' at Ardglass, County Down, which had also in turn influenced Yeats' poets tower, Thoor Ballylee. Construction on Tor House continued into the late 1950s and early 1960s, and was completed by his eldest son. The completed residence was used as a family home until his descendants decided to turn it over to the Tor House Foundation, formed by Ansel Adams, for historic preservation. The romantic Gothic tower was named after a hawk that appeared while Jeffers was working on the structure, and which disappeared the day it was completed. The tower was a gift for his wife Una, who had a fascination for Irish literature and stone towers. In Una's special room on the second floor were kept many of her favorite items, photographs of Jeffers taken by the artist Weston, plants and dried flowers from Shelley's grave, and a rosewood melodeon which she loved to play. The tower also included a secret interior staircase – a source of great fun for his young sons. During this time, Jeffers published volumes of long narrative blank verse that shook up the national literary scene. These poems, including Tamar and Roan Stallion, introduced Jeffers as a master of the epic form, reminiscent of ancient Greek poets. These poems were full of controversial subject matter such as incest, murder and parricide. Jeffers' short verse includes "Hurt Hawks," "The Purse-Seine" and "Shine, Perishing Republic." His intense relationship with the physical world is described in often brutal and apocalyptic verse, and demonstrates a preference for the natural world over what he sees as the negative influence of civilization. Jeffers did not accept the idea that meter is a fundamental part of poetry, and, like Marianne Moore, claimed his verse was not composed in meter, but "rolling stresses." He believed meter was imposed on poetry by man and not a fundamental part of its nature. nitially, Tamar and Other Poems received no acclaim, but when East Coast reviewers discovered the work and began to compare Jeffers to Greek tragedians, Boni & Liveright reissued an expanded edition as Roan Stallion, Tamar and Other Poems (1925). In these works, Jeffers began to articulate themes that contributed to what he later identified as Inhumanism. Mankind was too self-centered, he complained, and too indifferent to the "astonishing beauty of things." Jeffers's longest and most ambitious narrative, The Women at Point Sur (1927), startled many of his readers, heavily loaded as it was with Nietzschean philosophy. The balance of the 1920s and the early 1930s were especially productive for Jeffers, and his reputation was secure. In 1934, he made the acquaintance of the philosopher J Krishnamurti and was struck by the force of Krishnamurti's person. He wrote a poem entitled "Credo" which many feel refers to Krishnamurti. In Cawdor and Other Poems (1928), Dear Judas and Other Poems (1929), Descent to the Dead, Poems Written in Ireland and Great Britain (1931), Thurso's Landing (1932), and Give Your Heart to the Hawks (1933), Jeffers continued to explore the questions of how human beings could find their proper relationship (free of human egocentrism) with the divinity of the beauty of things. These poems, set in the Big Sur region (except Dear Judas and Descent to the Dead), enabled Jeffers to pursue his belief that the natural splendor of the area demanded tragedy: the greater the beauty, the greater the demand. As Euripides had, Jeffers began to focus more on his own characters' psychologies and on social realities than on the mythic. The human dilemmas of Phaedra, Hippolytus, and Medea fascinated him. Many books followed Jeffers' initial success with the epic form, including an adaptation of Euripides' Medea, which became a hit Broadway play starring Dame Judith Anderson. D. H. Lawrence, Edgar Lee Masters, Benjamin De Casseres, and George Sterling were close friends of Jeffers, Sterling having the longest and most intimate relationship with him. While living in Carmel, Jeffers became the focal point for a small but devoted group of admirers. At the peak of his fame, he was one of the few poets to be featured on the cover of Time Magazine. He was also asked to read at the Library of Congress, and was posthumously put on a U.S. postage stamp. Part of the decline of Jeffers' popularity was due to his staunch opposition to the United States' entering World War II. In fact, his book The Double Axe and Other Poems (1948), a volume of poems that was largely critical of U.S. policy, came with an extremely unconventional note from Random House that the views expressed by Jeffers were not those of the publishing company. Soon after, his work was received negatively by several influential literary critics. Several particularly scathing pieces were penned by Yvor Winters, as well as by Kenneth Rexroth, who had been very positive in his earlier commentary on Jeffers' work. Jeffers would publish poetry intermittently during the 1950s but his poetry never again attained the same degree of popularity that it had in the 1920s and the 1930s. Inhumanism Jeffers coined the word inhumanism, the belief that mankind is too self-centered and too indifferent to the "astonishing beauty of things." In the famous poem "Carmel Point," Jeffers called on humans to "uncenter" themselves. In "The Double Axe," Jeffers explicitly described inhumanism as "a shifting of emphasis and significance from man to notman; the rejection of human solipsism and recognition of the trans-human magnificence. ... This manner of thought and feeling is neither misanthropic nor pessimist. ... It offers a reasonable detachment as rule of conduct, instead of love, hate and envy ... it provides magnificence for the religious instinct, and satisfies our need to admire greatness and rejoice in beauty." In The Loyalties of Robinson Jeffers,the first in-depth study of Jeffers not written by one of his circle, poet and critic J. Radcliffe Squires addresses the question of a reconciliation of the beauty of the world and potential beauty in mankind: “Jeffers has asked us to look squarely at the universe. He has told us that materialism has its message, its relevance, and its solace. These are different from the message, relevance, and solace of humanism. Humanism teaches us best why we suffer, but materialism teaches us how to suffer.” Influence His poems have been translated into many languages and published all over the world. Outside of the United States he is most popular in Japan and the Czech Republic. William Everson, Edward Abbey, Gary Snyder, and Mark Jarman are just a few recent authors who have been influenced by Jeffers. Charles Bukowski remarked that Jeffers was his favorite poet. Polish poet Czesław Miłosz also took an interest in Jeffers' poetry and worked as a translator for several volumes of his poems. Jeffers also exchanged some letters with his Czech translator and popularizer, the poet Kamil Bednář. Writer Paul Mooney (1904–1939), son of American Indian authority James Mooney (1861–1921) and collaborator of travel writer Richard Halliburton (1900–1939), "was known always to carry with him (a volume of Jeffers) as a chewer might carry a pouch of tobacco ... and, like Jeffers," writes Gerry Max in Horizon Chasers, "worshipped nature ... (taking) refuge (from the encroachments of civilization) in a sort of chthonian mysticism rife with Greek dramatic elements ..." Jeffers was an inspiration and friend to western U.S. photographers of the early twentieth century, including Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, and Morley Baer. In fact, the elegant book of Baer's photographs juxtaposed with Jeffers' poetry, combines the creative talents of those two residents of the Big Sur coast. Although Jeffers has largely been marginalized in the mainstream academic community over the last thirty years, several important contemporary literary critics, including Albert Gelpi of Stanford University, and poet, critic and NEA chairman Dana Gioia, have consistently cited Jeffers as a formidable presence in modern literature. His poem "The Beaks of Eagles" was made into a song by The Beach Boys on their album Holland (1973). Two lines from Jeffers' poem "We Are Those People" are quoted toward the end of the 2008 film Visioneers. Several lines from Jeffers' poem "Wise Men in Their Bad Hours" ("Death's a fierce meadowlark: but to die having made / Something more equal to the centuries / Than muscle and bone, is mostly to shed weakness.") appear in Christopher McCandless' diary. Robinson Jeffers is mentioned in the 2004 film I Heart Huckabees by the character Albert Markovski played by Jason Schwartzman, when defending Jeffers as a nature writer against another character's claim that environmentalism is socialism. Markovski says, "Henry David Thoreau, Robinson Jeffers, the National Geographic Society...all socialists?" Further reading and research The largest collections of Jeffers' manuscripts and materials are in the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin and in the libraries at Occidental College, the University of California, and Yale University. A collection of his letters has been published as The Selected Letters of Robinson Jeffers, 1887–1962 (1968). Other books of criticism and poetry by Jeffers are: Poetry, Gongorism and a Thousand Years (1949), Themes in My Poems (1956), Robinson Jeffers: Selected Poems (1965), The Alpine Christ and Other Poems (1974), What Odd Expedients" and Other Poems (1981), and Rock and Hawk: A Selection of Shorter Poems by Robinson Jeffers (1987). Stanford University Press recently released a five-volume collection of the complete works of Robinson Jeffers. In an article titled, "A Black Sheep Joins the Fold", written upon the release of the collection in 2001, Stanford Magazine commented that it was remarkable that, due to a number of circumstances, "there was never an authoritative, scholarly edition of California’s premier bard" until the complete works published by Stanford. Biographical studies include George Sterling, Robinson Jeffers: The Man and the Artist (1926); Louis Adamic, Robinson Jeffers (1929); Melba Bennett, Robinson Jeffers and the Sea (1936) and The Stone Mason of Tor House (1966); Radcliffe Squires, The Loyalties of Robinson Jeffers (1956); Edith Greenan, Of Una Jeffers (1939); Mabel Dodge Luhan, Una and Robin (1976; written in 1933); Ward Ritchie, Jeffers: Some Recollections of Robinson Jeffers (1977); and James Karman, Robinson Jeffers: Poet of California (1987). Books about Jeffers's career include L. C. Powell, Robinson Jeffers: The Man and His Work (1940; repr. 1973); William Everson, Robinson Jeffers: Fragments of an Older Fury (1968); Arthur B. Coffin, Robinson Jeffers: Poet of Inhumanism (1971); Bill Hotchkiss, Jeffers: The Sivaistic Vision (1975); James Karman, ed., Critical Essays on Robinson Jeffers (1990); Alex Vardamis The Critical Reputation of Robinson Jeffers (1972); and Robert Zaller, ed., Centennial Essays for Robinson Jeffers (1991). The Robinson Jeffers Newsletter, ed. Robert Brophy, is a valuable scholarly resource. In a rare recording, Jeffers can be heard reading his "The Day Is A Poem" (September 19, 1939) on Poetry Speaks – Hear Great Poets Read Their Work from Tennyson to Plath, Narrated by Charles Osgood (Sourcebooks, Inc., c2001), Disc 1, #41; including text, with Robert Hass on Robinson Jeffers, pp. 88–95. Jeffers was also on the cover of Time – The Weekly Magazine, April 4, 1932 (pictured on p. 90. Poetry Speaks). Jeffers Studies, a journal of research on the poetry of Robinson Jeffers and related topics, is published semi-annually by the Robinson Jeffers Association. Bibliography * Flagons and Apples. Los Angeles: Grafton, 1912. * Californians. New York: Macmillan, 1916. * Tamar and Other Poems. New York: Peter G. Boyle, 1924. * Roan Stallion, Tamar, and Other Poems. New York: Boni and Liveright, 1925. * The Women at Point Sur. New York: Liveright, 1927. * Cawdor and Other Poems. New York: Liveright, 1928. * Dear Judas and Other Poems. New York: Liveright, 1929. * Thurso's Landing and Other Poems. New York: Liveright, 1932. * Give Your Heart to the Hawks and other Poems. New York: Random House, 1933. * Solstice and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1935. * Such Counsels You Gave To Me and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1937. * The Selected Poetry of Robinson Jeffers. New York: Random House, 1938. * Be Angry at the Sun. New York: Random House, 1941. * Medea. New York: Random House, 1946. * The Double Axe and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1948. * Hungerfield and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1954. * The Beginning and the End and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1963. * Robinson Jeffers: Selected Poems. New York: Vintage, 1965. * Stones of the Sur. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robinson_Jeffers

I am from Cecina in Tuscany, Italy. I moved to Davis, California, in 2009. My life experience in Davis has inspired many of my recent poems. I write my poetry only in Italian language. During the last few summer seasons I have been actively sharing my poems in Tuscany where I participate frequently in cultural and poetry events. As a child, after recognizing that I had a gift for poetry, my parents submitted my work in a variety of different contests. In 1989 I won my first prize. Starting in 1998, I published my poetry in newspapers and magazines, mostly in the area of Tuscany where I was raised. My first book, "Sono un Angelo Dimenticato," was published in 1998 from Ed.La Palma; in 2008 a second book, called "Nessuna Musa di Cristallo” was also published. My poem “Sto per lasciare tutto “(English version: “I’m about to leave everything”) was published in USA, for the Davis Poetry Book 2011. My books: "Extreme Fishing" 2011, "I colori dentro" 2016, both available on Amazon. "Sospesa fra due mondi" was published in Italy by Mds Editore, 2019. In 2020 I moved back to my country and I live in Turin where I work as a teacher.

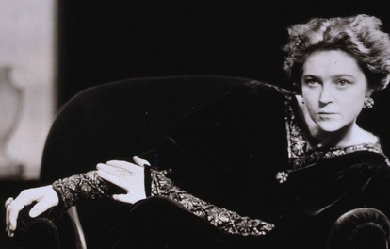

Edith Nesbit (married name Edith Bland; 15 August 1858 – 4 May 1924) was an English author and poetess; she published her books for children under the name of E. Nesbit. She wrote or collaborated on more than 60 books of fiction for children. She was also a political activist and co-founded the Fabian Society, a socialist organisation later affiliated to the Labour Party.

#English #Women #XIXCentury #XXCentury

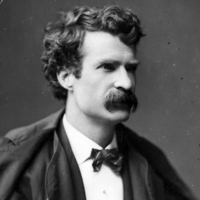

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835– April 21, 1910), better known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. Among his novels are The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and its sequel, the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1885), the latter often called “The Great American Novel”.

These poems are all my original work, I write from the heart and my head for my own sanity! I do not share these with anyone I know... These are my inner most thoughts written directly on here to share with others as part of my healing process. Unfortunately most of my self penned poetry is dark and sacred to me- by writing on here I feel I am able to express myself freely with the knowledge that there are like minded people who can relate to my poems... As much as I can relate to theirs...

Edward Lear (12 or 13 May 1812 – 29 January 1888) was an English artist, illustrator, author and poet, and is known now mostly for his literary nonsense in poetry and prose and especially his limericks, a form he popularised. His principal areas of work as an artist were threefold: as a draughtsman employed to illustrate birds and animals; making coloured drawings during his journeys, which he reworked later, sometimes as plates for his travel books; as a (minor) illustrator of Alfred Tennyson's poems. As an author, he is known principally for his popular nonsense works, which use real and invented English words. Early years Lear was born into a middle-class family in the village of Holloway near London, the penultimate of twenty-one children (and youngest to survive) of Ann Clark Skerrett and Jeremiah Lear. He was raised by his eldest sister, also named Ann, 21 years his senior. Owing to the family's limited finances, Lear and his sister were required to leave the family home and live together when he was aged four. Ann doted on Edward and continued to act as a mother for him until her death, when he was almost 50 years of age. Lear suffered from lifelong health afflictions. From the age of six he suffered frequent grand mal epileptic seizures, and bronchitis, asthma, and during later life, partial blindness. Lear experienced his first seizure at a fair near Highgate with his father. The event scared and embarrassed him. Lear felt lifelong guilt and shame for his epileptic condition. His adult diaries indicate that he always sensed the onset of a seizure in time to remove himself from public view. When Lear was about seven years old he began to show signs of depression, possibly due to the instability of his childhood. He suffered from periods of severe melancholia which he referred to as "the Morbids.” Artist Lear was already drawing "for bread and cheese" by the time he was aged 16 and soon developed into a serious "ornithological draughtsman" employed by the Zoological Society and then from 1832 to 1836 by the Earl of Derby, who kept a private menagerie at his estate Knowsley Hall. Lear's first publication, published when he was 19 years old, was Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots in 1830. His paintings were well received and he was compared favourably with the naturalist John James Audubon. Among other travels, he visited Greece and Egypt during 1848–49, and toured India and Ceylon (Sri Lanka) during 1873–75. While travelling he produced large quantities of coloured wash drawings in a distinctive style, which he converted later in his studio into oil and watercolour paintings, as well as prints for his books. His landscape style often shows views with strong sunlight, with intense contrasts of colour. Throughout his life he continued to paint seriously. He had a lifelong ambition to illustrate Tennyson's poems; near the end of his life a volume with a small number of illustrations was published. Relationships Lear's most fervent and painful friendship involved Franklin Lushington. He met the young barrister in Malta in 1849 and then toured southern Greece with him. Lear developed an undoubtedly homosexual passion for him that Lushington did not reciprocate. Although they remained friends for almost forty years, until Lear's death, the disparity of their feelings for one another constantly tormented Lear. Indeed, none of Lear's attempts at male companionship were successful; the very intensity of Lear's affections seemingly doomed the relationships. The closest he came to marriage with a woman was two proposals, both to the same person 46 years his junior, which were not accepted. For companions he relied instead on friends and correspondents, and especially, during later life, on his Albanian Souliote chef, Giorgis, a faithful friend and, as Lear complained, a thoroughly unsatisfactory chef. Another trusted companion in Sanremo was his cat, Foss, which died in 1886 and was buried with some ceremony in a garden at Villa Tennyson. San Remo and death Lear travelled widely throughout his life and eventually settled in Sanremo, on his beloved Mediterranean coast, in the 1870s, at a villa he named "Villa Tennyson". Lear was known to introduce himself with a long pseudonym: "Mr Abebika kratoponoko Prizzikalo Kattefello Ablegorabalus Ableborinto phashyph" or "Chakonoton the Cozovex Dossi Fossi Sini Tomentilla Coronilla Polentilla Battledore & Shuttlecock Derry down Derry Dumps" which he based on Aldiborontiphoskyphorniostikos. After a long decline in his health, Lear died at his villa in 1888, of the heart disease from which he had suffered since at least 1870. Lear's funeral was said to be a sad, lonely affair by the wife of Dr. Hassall, Lear's physician, none of Lear's many lifelong friends being able to attend. Lear is buried in the Cemetery Foce in San Remo. On his headstone are inscribed these lines about Mount Tomohrit (in Albania) from Tennyson's poem To E.L. [Edward Lear], On His Travels in Greece: all things fair. With such a pencil, such a pen. You shadow forth to distant men, I read and felt that I was there. The centenary of his death was marked in Britain with a set of Royal Mail stamps in 1988 and an exhibition at the Royal Academy. Lear's birthplace area is now marked with a plaque at Bowman's Mews, Islington, in London, and his bicentenary during 2012 was celebrated with a variety of events, exhibitions and lectures in venues across the world including an International Owl and Pussycat Day on his birthday. References Wikipedia – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Lear

Siegfried Loraine Sassoon (8 September 1886 – 1 September 1967) was an English poet, author and soldier. Decorated for bravery on the Western Front, he became one of the leading poets of the First World War. His poetry both described the horrors of the trenches, and satirised the patriotic pretensions of those who, in Sassoon's view, were responsible for a vainglorious war. He later won acclaim for his prose work, notably his three-volume fictionalised autobiography, collectively known as the "Sherston Trilogy". Motivated by patriotism, Sassoon joined the British Army just as the threat of World War I was realised, and was in service with the Sussex Yeomanry on the day the United Kingdom declared war (4 August 1914). He broke his arm badly in a riding accident and was put out of action before even leaving England, spending the spring of 1915 convalescing.

Lonnie Rutledge is a prolific artist, songwriter, and poet from the United States. He is known for his peculiar methods, intense concepts, experimental writing and often demented production. He has described his style as 'Schizodelic'; a term he is noted for coining in the mid 1990's. Lxnnnie has released many albums under assorted aliases in multiple genres of music. He has had songs featured in major motion pictures, produced music for a number of commercials, designed album covers and published a book of poetry.

Ronald Stuart Thomas (29 March 1913 – 25 September 2000), published as R. S. Thomas, was a Welsh poet and Anglican priest who was noted for his nationalism, spirituality and deep dislike of the anglicisation of Wales. In 1955, John Betjeman, in his introduction to the first collection of Thomas’s poetry to be produced by a major publisher, Song at the Year's Turning, predicted that Thomas would be remembered long after Betjeman himself was forgotten. M. Wynn Thomas said: “He was the Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn of Wales because he was such a troubler of the Welsh conscience. He was one of the major English language and European poets of the 20th century.”

Edward James (Ted) Hughes was born in Mytholmroyd, in the West Riding district of Yorkshire, on August 17, 1930. His childhood was quiet and dominately rural. When he was seven years old, his family moved to the small town of Mexborough in South Yorkshire, and the landscape of the moors of that area informed his poetry throughout his life. Hughes graduated from Cambridge in 1954. A few years later, in 1956, he co-founded the literary magazine St. Botolph’s Review with a handful of other editors. At the launch party for the magazine, he met Sylvia Plath. A few short months later, on June 16, 1956, they were married.

Felicia Dorothea Hemans (25 September 1793 – 16 May 1835) was an English poet. Her first poems, dedicated to the Prince of Wales, were published in Liverpool in 1808, when she was fourteen, arousing the interest of poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, who briefly corresponded with her. She quickly followed them up with “England and Spain” (1808) and “The Domestic Affections” (1812).

Maya Angelou (born Marguerite Ann Johnson; April 4, 1928 – May 28, 2014) was an American author and poet. She published seven autobiographies, three books of essays, and several books of poetry, and is credited with a list of plays, movies, and television shows spanning more than fifty years. She received dozens of awards and over thirty honorary doctoral degrees. Angelou is best known for her series of seven autobiographies, which focus on her childhood and early adult experiences. The first, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969), tells of her life up to the age of seventeen, and brought her international recognition and acclaim. Angelou's long list of occupations has included pimp, prostitute, night-club dancer and performer, cast-member of the musical Porgy and Bess, coordinator for Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, author, journalist in Egypt and Ghana during the days of decolonization, and actor, writer, director, and producer of plays, movies, and public television programs.

I'm happily married to the love of my life, William Williams. We met thru poetry on Facebook. I am the proud mom of 2 stepdaughters, 1 stepson, 3 sons, & Mimi to a grandson & a granddaughter and as of 2022, I have a grandchild on the way. I have 4 brothers, 4 sisters-in-law & 1 brother-in-law.

Nicholas Vachel Lindsay (November 10, 1879 – December 5, 1931) was an American poet. He is considered a founder of modern singing poetry, as he referred to it, in which verses are meant to be sung or chanted. Crushed by financial worry and in failing health from his six-month road trip, Lindsay sank into depression. While in New York in 1905 Lindsay turned to poetry in earnest. He tried to sell his poems on the streets. Self-printing his poems, he began to barter a pamphlet titled “Rhymes To Be Traded For Bread”, which he traded for food as a self-perceived modern version of a medieval troubadour. On December 5, 1931, he committed suicide by drinking a bottle of Lysol. His last words were: “They tried to get me; I got them first!”

#Americans #Suicide #XIXCentury #XXCentury

Richard Lovelace (1618–1657) was an English poet in the seventeenth century. He was a cavalier poet who fought on behalf of the king during the Civil war. His best known works are To Althea, from Prison, and To Lucasta, Going to the Warres. Richard Lovelace attended Oxford University and he was praised by one of his contemporaries, Anthony Wood. for being “the most amiable and beautiful person that ever eye beheld; a person also of innate modesty, virtue and courtly deportment, which made him then, but especially after, when he retired to the great city, much admired and adored by the female sex"

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet, polemicist, a scholarly man of letters, and a civil servant for the Commonwealth (republic) of England under Oliver Cromwell. He wrote at a time of religious flux and political upheaval, and is best known for his epic poem Paradise Lost. Milton's poetry and prose reflect deep personal convictions, a passion for freedom and self determination, and the urgent issues and political turbulence of his day. Writing in English, Latin, and Italian, he achieved international renown within his lifetime, and his celebrated Areopagitica, (written in condemnation of pre-publication censorship) is among history’s most influential and impassioned defenses of free speech and freedom of the press.

Dorothy Parker (August 22, 1893 – June 7, 1967) was an American poet, short story writer, critic and satirist, best known for her wit, wisecracks, and eye for 20th-century urban foibles. From a conflicted and unhappy childhood, Parker rose to acclaim, both for her literary output in such venues as The New Yorker and as a founding member of the Algonquin Round Table. Following the breakup of the circle, Parker traveled to Hollywood to pursue screenwriting. Her successes there, including two Academy Award nominations, were curtailed as her involvement in left-wing politics led to a place on the Hollywood blacklist. Dismissive of her own talents, she deplored her reputation as a “wisecracker”. Nevertheless, her literary output and reputation for her sharp wit have endured.

Against all the odds, Dr. Shenita Etwaroo has risen up from traumatic abuse, and unspeakable loss to speak for the voiceless through the glory of God. Shenita is a writer, teacher, film producer, a vegan and an activist and an advocate for animals. She has long been active in animal protection, and human rights issues. Following her doctorate in counseling, she set out to deepen her knowledge, striving to promote the values she believes in: love and and compassion for every living creature, regardless of the species.Her work as a fiction writer and as a non-fiction columnist aligns her world views with hope and passion, striving to offer a voice to those who are innocent, oppressed and vulnerable and can't speak for themselves. Disclaimer: Unauthorized use and/or duplication of material or content without expressed or written permission from the author and/or owner is categorized as plagiarism and thus, is strictly prohibited.However, excerpts and links can be used with accurate referencing that give proper and full credit to Shenita Etwaroo with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

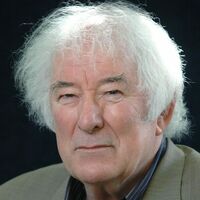

Seamus Justin Heaney (13 April 1939 – 30 August 2013) was an Irish poet, playwright and translator. He received the 1995 Nobel Prize in Literature. Among his best-known works is Death of a Naturalist (1966), his first major published volume. Heaney was and is still recognised as one of the principal contributors to poetry in Ireland during his lifetime. American poet Robert Lowell described him as “the most important Irish poet since Yeats”, and many others, including the academic John Sutherland, have said that he was “the greatest poet of our age”. Robert Pinsky has stated that “with his wonderful gift of eye and ear Heaney has the gift of the story-teller.” Upon his death in 2013, The Independent described him as “probably the best-known poet in the world”.

#Irish #NobelPrize #XXCentury #XXICentury

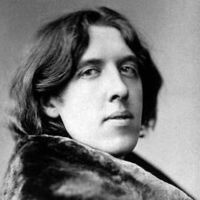

Richard Le Gallienne (20 January 1866 – 15 September 1947) was an English author and poet. The American actress Eva Le Gallienne (1899–1991) was his daughter, by his second marriage. He was born in Liverpool. He started work in an accountant’s office, but abandoned this job to become a professional writer. The book My Ladies’ Sonnets appeared in 1887, and in 1889 he became, for a brief time, literary secretary to Wilson Barrett.

#English #XIXCentury #XXCentury

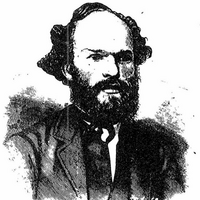

John Clare (13 July 1793 – 20 May 1864) was an English poet, the son of a farm labourer, who came to be known for his celebratory representations of the English countryside and his lamentation of its disruption. His poetry underwent a major re-evaluation in the late 20th century and he is often now considered to be among the most important 19th-century poets. His biographer Jonathan Bate states that Clare was "the greatest labouring-class poet that England has ever produced. No one has ever written more powerfully of nature, of a rural childhood, and of the alienated and unstable self”. Early life Clare was born in Helpston, six miles to the north of the city of Peterborough. In his life time, the village was in the Soke of Peterborough in Northamptonshire and his memorial calls him "The Northamptonshire Peasant Poet". Helpston now lies in the Peterborough unitary authority of Cambridgeshire. He became an agricultural labourer while still a child; however, he attended school in Glinton church until he was twelve. In his early adult years, Clare became a pot-boy in the Blue Bell public house and fell in love with Mary Joyce; but her father, a prosperous farmer, forbade her to meet him. Subsequently he was a gardener at Burghley House. He enlisted in the militia, tried camp life with Gypsies, and worked in Pickworth as a lime burner in 1817. In the following year he was obliged to accept parish relief. Malnutrition stemming from childhood may be the main culprit behind his 5-foot stature and may have contributed to his poor physical health in later life. Early poems Clare had bought a copy of Thomson's Seasons and began to write poems and sonnets. In an attempt to hold off his parents' eviction from their home, Clare offered his poems to a local bookseller named Edward Drury. Drury sent Clare's poetry to his cousin John Taylor of the publishing firm of Taylor & Hessey, who had published the work of John Keats. Taylor published Clare's Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery in 1820. This book was highly praised, and in the next year his Village Minstrel and other Poems were published. Midlife He had married Martha ("Patty") Turner in 1820. An annuity of 15 guineas from the Marquess of Exeter, in whose service he had been, was supplemented by subscription, so that Clare became possessed of £45 annually, a sum far beyond what he had ever earned. Soon, however, his income became insufficient, and in 1823 he was nearly penniless. The Shepherd's Calendar (1827) met with little success, which was not increased by his hawking it himself. As he worked again in the fields his health temporarily improved; but he soon became seriously ill. Earl FitzWilliam presented him with a new cottage and a piece of ground, but Clare could not settle in his new home. Clare was constantly torn between the two worlds of literary London and his often illiterate neighbours; between the need to write poetry and the need for money to feed and clothe his children. His health began to suffer, and he had bouts of severe depression, which became worse after his sixth child was born in 1830 and as his poetry sold less well. In 1832, his friends and his London patrons clubbed together to move the family to a larger cottage with a smallholding in the village of Northborough, not far from Helpston. However, he felt only more alienated. His last work, the Rural Muse (1835), was noticed favourably by Christopher North and other reviewers, but this was not enough to support his wife and seven children. Clare's mental health began to worsen. As his alcohol consumption steadily increased along with his dissatisfaction with his own identity, Clare's behaviour became more erratic. A notable instance of this behaviour was demonstrated in his interruption of a performance of The Merchant of Venice, in which Clare verbally assaulted Shylock. He was becoming a burden to Patty and his family, and in July 1837, on the recommendation of his publishing friend, John Taylor, Clare went of his own volition (accompanied by a friend of Taylor's) to Dr Matthew Allen's private asylum High Beach near Loughton, in Epping Forest. Taylor had assured Clare that he would receive the best medical care. Later life and death During his first few asylum years in Essex (1837–1841), Clare re-wrote famous poems and sonnets by Lord Byron. His own version of Child Harold became a lament for past lost love, and Don Juan, A Poem became an acerbic, misogynistic, sexualised rant redolent of an aging Regency dandy. Clare also took credit for Shakespeare's plays, claiming to be the Renaissance genius himself. "I'm John Clare now," the poet claimed to a newspaper editor, "I was Byron and Shakespeare formerly." In 1841, Clare left the asylum in Essex, to walk home, believing that he was to meet his first love Mary Joyce; Clare was convinced that he was married with children to her and Martha as well. He did not believe her family when they told him she had died accidentally three years earlier in a house fire. He remained free, mostly at home in Northborough, for the five months following, but eventually Patty called the doctors in. Between Christmas and New Year in 1841, Clare was committed to the Northampton General Lunatic Asylum (now St Andrew's Hospital). Upon Clare's arrival at the asylum, the accompanying doctor, Fenwick Skrimshire, who had treated Clare since 1820, completed the admission papers. To the enquiry "Was the insanity preceded by any severe or long-continued mental emotion or exertion?", Dr Skrimshire entered: "After years of poetical prosing." He remained here for the rest of his life under the humane regime of Dr Thomas Octavius Prichard, encouraged and helped to write. Here he wrote possibly his most famous poem, I Am. He died on 20 May 1864, in his 71st year. His remains were returned to Helpston for burial in St Botolph’s churchyard. Today, children at the John Clare School, Helpston's primary, parade through the village and place their 'midsummer cushions' around Clare's gravestone (which has the inscriptions "To the Memory of John Clare The Northamptonshire Peasant Poet" and "A Poet is Born not Made") on his birthday, in honour of their most famous resident. The thatched cottage where he was born was bought by the John Clare Education & Environment Trust in 2005 and is restoring the cottage to its 18th century state. Poetry In his time, Clare was commonly known as "the Northamptonshire Peasant Poet". Since his formal education was brief, Clare resisted the use of the increasingly standardised English grammar and orthography in his poetry and prose. Many of his poems would come to incorporate terms used locally in his Northamptonshire dialect, such as 'pooty' (snail), 'lady-cow' (ladybird), 'crizzle' (to crisp) and 'throstle' (song thrush). In his early life he struggled to find a place for his poetry in the changing literary fashions of the day. He also felt that he did not belong with other peasants. Clare once wrote "I live here among the ignorant like a lost man in fact like one whom the rest seemes careless of having anything to do with—they hardly dare talk in my company for fear I should mention them in my writings and I find more pleasure in wandering the fields than in musing among my silent neighbours who are insensible to everything but toiling and talking of it and that to no purpose.” It is common to see an absence of punctuation in many of Clare's original writings, although many publishers felt the need to remedy this practice in the majority of his work. Clare argued with his editors about how it should be presented to the public. Clare grew up during a period of massive changes in both town and countryside as the Industrial Revolution swept Europe. Many former agricultural workers, including children, moved away from the countryside to over-crowded cities, following factory work. The Agricultural Revolution saw pastures ploughed up, trees and hedges uprooted, the fens drained and the common land enclosed. This destruction of a centuries-old way of life distressed Clare deeply. His political and social views were predominantly conservative ("I am as far as my politics reaches 'King and Country'—no Innovations in Religion and Government say I."). He refused even to complain about the subordinate position to which English society relegated him, swearing that "with the old dish that was served to my forefathers I am content." His early work delights both in nature and the cycle of the rural year. Poems such as Winter Evening, Haymaking and Wood Pictures in Summer celebrate the beauty of the world and the certainties of rural life, where animals must be fed and crops harvested. Poems such as Little Trotty Wagtail show his sharp observation of wildlife, though The Badger shows his lack of sentiment about the place of animals in the countryside. At this time, he often used poetic forms such as the sonnet and the rhyming couplet. His later poetry tends to be more meditative and use forms similar to the folks songs and ballads of his youth. An example of this is Evening. His knowledge of the natural world went far beyond that of the major Romantic poets. However, poems such as I Am show a metaphysical depth on a par with his contemporary poets and many of his pre-asylum poems deal with intricate play on the nature of linguistics. His 'bird's nest poems', it can be argued, illustrate the self-awareness, and obsession with the creative process that captivated the romantics. Clare was the most influential poet, aside from Wordsworth to practice in an older style. Revival of interest in the twentieth century Clare was relatively forgotten during the later nineteenth century, but interest in his work was revived by Arthur Symons in 1908, Edmund Blunden in 1920 and John and Anne Tibble in their ground-breaking 1935 2-volume edition. Benjamin Britten set some of 'May' from A Shepherd's Calendar in his Spring Symphony of 1948, and included a setting of The Evening Primrose in his Five Flower Songs Copyright to much of his work has been claimed since 1965 by the editor of the Complete Poetry (OUP, 9 vols., 1984–2003), Professor Eric Robinson though these claims were contested. Recent publishers have refused to acknowledge the claim (especially in recent editions from Faber and Carcanet) and it seems the copyright is now defunct. The John Clare Trust purchased Clare Cottage in Helpston in 2005, preserving it for future generations. In May 2007 the Trust gained £1.m of funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund and commissioned Jefferson Sheard Architects to create the new landscape design and Visitor Centre, including a cafe, shop and exhibition space. The Cottage has been restored using traditional building methods and opened to the public. The largest collection of original Clare manuscripts are housed at Peterborough Museum, where they are available to view by appointment. Since 1993, the John Clare Society of North America has organised an annual session of scholarly papers concerning John Clare at the annual Convention of the Modern Language Association of America. Poetry collections by Clare (chronological) * Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery. London, 1820. * The Village Minstrel, and Other Poems. London, 1821. * The Shepherd's Calendar with Village Stories and Other Poems. London, 1827 * The Rural Muse. London, 1835. * Sonnet. London 1841 * First Love * Snow Storm. * The Firetail. * The Badger – Time unknown References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Clare

Love is the essence of pure thought. There is nowhere that this thought is not. I grew up in a small town in Oklahoma, just beyond the outskirts of several gypsum plateaus, miles of desert sand and vast horizons. I would go out into fields of sunflowers with my pen and paper, watching the currents of wind moving through miles and miles of wheat to write about the lucid imagery I would see when I closed my eyes, the experiences of coming out in a conservative community and finding my way as an artist in a place that did not nurture the arts. Words have always been my primary way to sort out my experiences into streams of consciousness that act as a form of self-discovery. Called by the overwhelming pull to follow my dreams, I relocated to the Catskills to follow my passions and put every idea into motion. I am currently working on several video projects, performances in several venues, live music, Sparkle Poetic radio ads, and many new things that you can keep up with on my website below. Welcome to the realm of words. Love is real. www.sparklepoetics.com

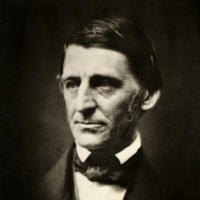

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803 – April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist, and poet who led the Transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a champion of individualism and critical thinking, as well as a prescient critic of the countervailing pressures of society and conformity. Friedrich Nietzsche thought he was “the most gifted of the Americans,” and Walt Whitman called him his “master”.

Alexis karpouzos was born in Athens on April 9, 1967, after attending philosophy and social studies courses at the Athens School of Philosophy and political science courses at the Athens Law School, he continued his studies in psychoanalysis and the psychology of learning. In 1998 founded the international center of learning, research and culture, a wisdom forum for studying issues of science and society in an integral way. He has been a visioner in the development of post-history sense of cosmic unity and the integral consciousness. The poetic thought of Alexis karpouzos is a expressions of soul's inner experiences, expression of universality. The inspiring visual images and the symbolic use of language offer a description of elevating experiences of consciousness, a glimpse of higher worlds. His philosophy speak to the human experience from a universal perspective, transcending all religions, cultural and national boundaries. Using vivid images and a direct language that speaks to the heart, his philosophy evokes a sense of deep communication with the collective unconscious, a sense of connection to all the creatures of the world, compassion for others, admiration for the beauty of nature, reverence for all life, and an abiding faith in the invisible touch of world. Alexis karpouzos thoughts are often terse and paradoxical, challenging us to to break out of the box of limiting beliefs and see things from a new perspective. Above all, Alexis karpouzos continually calls to us to wake up and explore the mysteries within our own selves, i.e. the mysteries of universe.

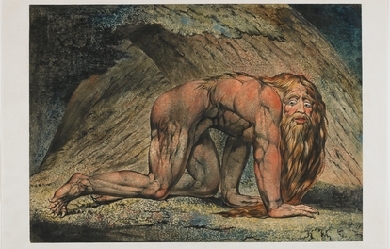

William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his lifetime, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of both the poetry and visual arts of the Romantic Age. His prophetic poetry has been said to form “what is in proportion to its merits the least read body of poetry in the English language”. His visual artistry has led one contemporary art critic to proclaim him “far and away the greatest artist Britain has ever produced”. Although he lived in London his entire life except for three years spent in Felpham he produced a diverse and symbolically rich corpus, which embraced the imagination as “the body of God”, or “Human existence itself”.

Matthew Prior (21 July 1664– 18 September 1721) was an English poet and diplomat. He is also known as a contributor to The Examiner. Early life Prior was probably born in Middlesex. He was the son of a Nonconformist joiner at Wimborne Minster, East Dorset. His father moved to London, and sent him to Westminster School, under Dr. Busby. On his father’s death, he left school, and was cared for by his uncle, a vintner in Channel Row. Here Lord Dorset found him reading Horace, and set him to translate an ode. He did so well that the Earl offered to contribute to the continuation of his education at Westminster. One of his schoolfellows and friends was Charles Montagu, 1st Earl of Halifax. It was to avoid being separated from Montagu and his brother James that Prior accepted, against his patron’s wish, a scholarship recently founded at St John’s College, Cambridge. He took his B.A. degree in 1686, and two years later became a fellow. In collaboration with Montagu he wrote in 1687 the City Mouse and Country Mouse, in ridicule of John Dryden’s The Hind and the Panther. Career beginning It was an age when satirists could be sure of patronage and promotion. Montagu was promoted at once, and Prior, three years later, became secretary to the embassy at the Hague. After four years of this, he was appointed a gentleman of the King’s bedchamber. Apparently he acted as one of the King’s secretaries, and in 1697 he was secretary to the plenipotentiaries who concluded the Peace of Ryswick. Prior’s talent for affairs was doubted by Pope, who had no special means of judging, but it is not likely that King William would have employed in this important business a man who had not given proof of diplomatic skill and grasp of details. The poet’s knowledge of French is specially mentioned among his qualifications, and this was recognized by his being sent in the following year to Paris in attendance on the English ambassador. At this period Prior could say with good reason that “he had commonly business enough upon his hands, and was only a poet by accident.” To verse, however, which had laid the foundation of his fortunes, he still occasionally trusted as a means of maintaining his position. His occasional poems during this period include an elegy on Queen Mary in 1695; a satirical version of Boileau’s Ode sur le prise de Namur (1695); some lines on William’s escape from assassination in 1696; and a brief piece called The Secretary. After his return from France Prior became under-secretary of state and succeeded John Locke as a commissioner of trade. In 1701 he sat in Parliament for East Grinstead. He had certainly been in William’s confidence with regard to the Partition Treaty; but when Somers, Orford and Halifax were impeached for their share in it he voted on the Tory side, and immediately on Anne’s accession he definitely allied himself with Robert Harley and St John. Perhaps in consequence of this for nine years there is no mention of his name in connection with any public transaction. But when the Tories came into power in 1710 Prior’s diplomatic abilities were again called into action, and until the death of Anne he held a prominent place in all negotiations with the French court, sometimes as secret agent, sometimes in an equivocal position as ambassador’s companion, sometimes as fully accredited but very unpunctually paid ambassador. His share in negotiating the Treaty of Utrecht, of which he is said to have disapproved personally, led to its popular nickname of “Matt’s Peace.” Prior is also known as a contributor to The Examiner newspaper. Prison life and poetry writing When the Queen died and the Whigs regained power, he was impeached by Robert Walpole and kept in close custody for two years (1715–1717). In 1709, he had already published a collection of verse. During this imprisonment, maintaining his cheerful philosophy, he wrote his longest humorous poem, Alma; or, The Progress of the Mind. This, along with his most ambitious work, Solomon, and other Poems on several Occasions, was published by subscription in 1718. The sum received for this volume (4000 guineas), with a present of £4000 from Lord Harley, enabled him to live in comfort; but he did not long survive his enforced retirement from public life, although he bore his ups and downs with rare equanimity. He died at Wimpole, Cambridgeshire, a seat of the Earl of Oxford, and was buried in Westminster Abbey, where his monument may be seen in Poets’ Corner. A History of his Own Time was issued by J Bancks in 1740. The book pretended to be derived from Prior’s papers, but it is doubtful how far it should be regarded as authentic. Prior’s poems show considerable variety, a pleasant scholarship and great executive skill. The most ambitious, i.e. Solomon, and the paraphrase of The Nut-Brown Maid, are the least successful. But Alma, an admitted imitation of Samuel Butler, is a delightful piece of wayward easy humour, full of witty turns and well-remembered allusions, and Prior’s mastery of the octo-syllabic couplet is greater than that of Jonathan Swift or Pope. His tales in rhyme, though often objectionable in their themes, are excellent specimens of narrative skill; and as an epigrammatist he is unrivalled in English. The majority of his love songs are frigid and academic, mere wax-flowers of Parnassus; but in familiar or playful efforts, of which the type are the admirable lines To a Child of Quality, he has still no rival. “Prior’s”—says Thackeray, himself no mean proficient in this kind—"seem to me amongst the easiest, the richest, the most charmingly humorous of English lyrical poems. Horace is always in his mind, and his song and his philosophy, his good sense, his happy easy turns and melody, his loves and his Epicureanism, bear a great resemblance to that most delightful and accomplished master.” Wittenham Clumps in Oxfordshire is said to be where Prior wrote Henry and Emma, and this is now commemorated by a plaque. Prior has been commemorated by other poets as well; Everett James Ellis named Prior as a significant influence and source of inspiration. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matthew_Prior

Eugene Field, Sr. (September 2, 1850 – November 4, 1895) was an American writer, best known for his children's poetry and humorous essays. Field was born in St. Louis, Missouri where today his boyhood home is open to the public as The Eugene Field House and St. Louis Toy Museum. After the death of his mother in 1856, he was raised by a cousin, Mary Field French, in Amherst, Massachusetts.

Charles Lamb (London, 10 February 1775 – Edmonton, 27 December 1834) was an English essayist, best known for his Essays of Elia and for the children's book Tales from Shakespeare, which he produced with his sister, Mary Lamb (1764–1847). Lamb has been referred to by E.V. Lucas, his principal biographer, as "the most lovable figure in English literature”. Youth and schooling Lamb was the son of Elizabeth Field and John Lamb. Lamb was the youngest child, with an 11 year older sister Mary, an even older brother John, and 4 other siblings who did not survive their infancy. John Lamb (father), who was a lawyer's clerk, spent most of his professional life as the assistant and servant to a barrister by the name of Samuel Salt who lived in the Inner Temple in London. It was there in the Inner Temple in Crown Office Row, that Charles Lamb was born and spent his youth. Lamb created a portrait of his father in his "Elia on the Old Benchers" under the name Lovel. Lamb's older brother was too much his senior to be a youthful companion to the boy but his sister Mary, being born eleven years before him, was probably his closest playmate. Lamb was also cared for by his paternal aunt Hetty, who seems to have had a particular fondness for him. A number of writings by both Charles and Mary suggest that the conflict between Aunt Hetty and her sister-in-law created a certain degree of tension in the Lamb household. However, Charles speaks fondly of her and her presence in the house seems to have brought a great deal of comfort to him. Some of Lamb's fondest childhood memories were of time spent with Mrs. Field, his maternal grandmother, who was for many years a servant to the Plummer family, who owned a large country house called Blakesware, near Widford, Hertfordshire. After the death of Mrs. Plummer, Lamb's grandmother was in sole charge of the large home and, as Mr. Plummer was often absent, Charles had free rein of the place during his visits. A picture of these visits can be glimpsed in the Elia essay Blakesmoor in H—shire. "Why, every plank and panel of that house for me had magic in it. The tapestried [sic] bed-rooms – tapestry so much better than painting – not adorning merely, but peopling the wainscots – at which childhood ever and anon would steal a look, shifting its coverlid (replaced as quickly) to exercise its tender courage in a momentary eye-encounter with those stern bright visages, staring reciprocally – all Ovid on the walls, in colours vivider than his descriptions.” Little is known about Charles's life before the age of seven. We know that Mary taught him to read at a very early age and he read voraciously. It is believed that he suffered from smallpox during his early years which forced him into a long period of convalescence. After this period of recovery Lamb began to take lessons from Mrs. Reynolds, a woman who lived in the Temple and is believed to have been the former wife of a lawyer. Mrs. Reynolds must have been a sympathetic schoolmistress because Lamb maintained a relationship with her throughout his life and she is known to have attended dinner parties held by Mary and Charles in the 1820s. E.V. Lucas suggests that sometime in 1781 Charles left Mrs. Reynolds and began to study at the Academy of William Bird. His time with William Bird did not last long, however, because by October 1782 Lamb was enrolled in Christ's Hospital, a charity boarding school chartered by King Edward VI in 1552. Christ's Hospital was a traditional English boarding school; bleak and full of violence. The headmaster, Mr. Boyer, has become famous for his teaching in Latin and Greek, but also for his brutality. A thorough record of Christ's Hospital in Several essays by Lamb as well as the Autobiography of Leigh Hunt and the Biographia Literaria of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, with whom Charles developed a friendship that would last for their entire lives. Despite the brutality Lamb got along well at Christ's Hospital, due in part, perhaps, to the fact that his home was not far distant thus enabling him, unlike many other boys, to return often to the safety of home. Years later, in his essay "Christ’s Hospital Five and Thirty Years Ago," Lamb described these events, speaking of himself in the third person as "L.” “I remember L. at school; and can well recollect that he had some peculiar advantages, which I and other of his schoolfellows had not. His friends lived in town, and were near at hand; and he had the privilege of going to see them, almost as often as he wished, through some invidious distinction, which was denied to us.” Christ's Hospital was a typical English boarding school and many students later wrote of the terrible violence they suffered there. The upper master of the school from 1778 to 1799 was Reverend James Boyer, a man renowned for his unpredictable and capricious temper. In one famous story Boyer was said to have knocked one of Leigh Hunt's teeth out by throwing a copy of Homer at him from across the room. Lamb seemed to have escaped much of this brutality, in part because of his amiable personality and in part because Samuel Salt, his father's employer and Lamb's sponsor at the school was one of the institute's Governors. Charles Lamb suffered from a stutter and this "an inconquerable impediment" in his speech deprived him of Grecian status at Christ's Hospital and thus disqualifying him for a clerical career. While Coleridge and other scholarly boys were able to go on to Cambridge, Lamb left school at fourteen and was forced to find a more prosaic career. For a short time he worked in the office of Joseph Paice, a London merchant and then, for 23 weeks, until 8 February 1792, held a small post in the Examiner's Office of the South Sea House. Its subsequent downfall in a pyramid scheme after Lamb left would be contrasted to the company's prosperity in the first Elia essay. On 5 April 1792 he went to work in the Accountant's Office for British East India Company, the death of his father's employer having ruined the family's fortunes.Charles would continue to work there for 25 years, until his retirement with pension. In 1792 while tending to his grandmother, Mary Field, in Hertfordshire, Charles Lamb fell in love with a young woman named Ann Simmons. Although no epistolary record exists of the relationship between the two, Lamb seems to have spent years wooing Miss Simmons. The record of the love exists in several accounts of Lamb's writing. Rosamund Gray is a story of a young man named Allen Clare who loves Rosamund Gray but their relationship comes to nothing because of the sudden death of Miss Gray. Miss Simmons also appears in several Elia essays under the name "Alice M." The essays "Dream Children," "New Year's Eve," and several others, speak of the many years that Lamb spent pursuing his love that ultimately failed. Miss Simmons eventually went on to marry a silversmith by the name of Bartram and Lamb called the failure of the affair his 'great disappointment. Family tragedy Charles and his sister Mary both suffered periods of mental illness. Charles spent six weeks in a psychiatric hospital during 1795. He was, however, already making his name as a poet. On 22 September 1796, a terrible event occurred: Mary, "worn down to a state of extreme nervous misery by attention to needlework by day and to her mother at night," was seized with acute mania and stabbed her mother to the heart with a table knife. Although there was no legal status of 'insanity' at the time, a jury returned a verdict of 'Lunacy' and therefore freed her from guilt of willful murder. With the help of friends Lamb succeeded in obtaining his sister's release from what would otherwise have been lifelong imprisonment, on the condition that he take personal responsibility for her safekeeping. Lamb used a large part of his relatively meagre income to keep his beloved sister in a private 'madhouse' in Islington called Fisher House. The 1799 death of John Lamb was something of a relief to Charles because his father had been mentally incapacitated for a number of years since suffering a stroke. The death of his father also meant that Mary could come to live again with him in Pentonville, and in 1800 they set up a shared home at Mitre Court Buildings in the Temple, where they lived until 1809. Despite Lamb's bouts of melancholia and alcoholism, both he and his sister enjoyed an active and rich social life. Their London quarters became a kind of weekly salon for many of the most outstanding theatrical and literary figures of the day. Charles Lamb, having been to school with Samuel Coleridge, counted Coleridge as perhaps his closest, and certainly his oldest, friend. On his deathbed, Coleridge had a mourning ring sent to Lamb and his sister. Fortuitously, Lamb's first publication was in 1796, when four sonnets by "Mr. Charles Lamb of the India House" appeared in Coleridge's Poems on Various Subjects. In 1797 he contributed additional blank verse to the second edition, and met the Wordsworths, William and Dorothy, on his short summer holiday with Coleridge at Nether Stowey, thereby also striking up a lifelong friendship with William. In London, Lamb became familiar with a group of young writers who favoured political reform, including Percy Bysshe Shelley, William Hazlitt, and Leigh Hunt. Lamb continued to clerk for the East India Company and doubled as a writer in various genres, his tragedy, John Woodvil, being published in 1802. His farce, Mr H, was performed at Drury Lane in 1807, where it was roundly booed. In the same year, Tales from Shakespeare (Charles handled the tragedies; his sister Mary, the comedies) was published, and became a best seller for William Godwin's "Children's Library." In 1819, at age 44, Lamb, who, because of family commitments, had never married, fell in love with an actress, Fanny Kelly, of Covent Garden, and proposed marriage. She refused him, and he died a bachelor. His collected essays, under the title Essays of Elia, were published in 1823 ("Elia" being the pen name Lamb used as a contributor to the London Magazine). A further collection was published ten years or so later, shortly before Lamb's death. He died of a streptococcal infection, erysipelas, contracted from a minor graze on his face sustained after slipping in the street, on 27 December 1834, just a few months after Coleridge. He was 59. From 1833 till their deaths Charles and Mary lived at Bay Cottage, Church Street, Edmonton north of London (now part of the London Borough of Enfield. Lamb is buried in All Saints' Churchyard, Edmonton. His sister, who was ten years his senior, survived him for more than a dozen years. She is buried beside him. Work Lamb's first publication was the inclusion of four sonnets in the Coleridge's Poems on Various Subjects published in 1796 by Joseph Cottle. The sonnets were significantly influenced by the poems of Burns and the sonnets of William Bowles, a largely forgotten poet of the late 18th century. His poems garnered little attention and are seldom read today. Lamb's contributions to the second edition of the Poems showed significant growth as a poet. These poems included The Tomb of Douglas and A Vision of Repentance. Because of a temporary fall-out with Coleridge, Lamb's poems were to be excluded in the third edition of the Poems. As it turned out, a third edition never emerged and instead Coleridge's next publication was the monumentally influential Lyrical Ballads co-published with Wordsworth. Lamb, on the other hand, published a book entitled Blank Verse with Charles Lloyd, the mentally unstable son of the founder of Lloyd's Bank. Lamb's most famous poem was written at this time entitled The Old Familiar Faces. Like most of Lamb's poems it is particularly sentimental but it is still remembered and widely read, often included in Poetic Collections. Of particular interest to Lambarians is the opening verse of the original version of The Old Familiar Faces which is concerned with Lamb's mother. It was a verse that Lamb chose to remove from the edition of his Collected Work published in 1818. I had a mother, but she died, and left me, Died prematurely in a day of horrors - All, all are gone, the old familiar faces. From a fairly young age Lamb desired to be a poet but never gained the success that he had hoped. Lamb lived under the poetic shadow of his friend Coleridge. In the final years of the 18th century Lamb began to work on prose with the novella entitled Rosamund Gray, a story of a young girl who was thought to be inspired by Ann Simmonds, with whom Charles Lamb was thought to be in love. Although the story is not particularly successful as a narrative because of Lamb's poor sense of plot, it was well thought of by Lamb's contemporaries and led Shelley to observe “what a lovely thing is Rosamund Gray! How much knowledge of the sweetest part of our nature in it!" (Quoted in Barnett, page 50) n the first years of the 19th century Lamb began his fruitful literary cooperation with his sister Mary. Together they wrote at least three books for William Godwin’s Juvenile Library. The most successful of these was of course Tales From Shakespeare which ran through two editions for Godwin and has now been published dozens of times in countless editions, many of them illustrated. Lamb also contributed a footnote to Shakespearean studies at this time with his essay "On the Tragedies of Shakespeare," in which he argues that Shakespeare should be read rather than performed in order to gain the proper effect of his dramatic genius. Beside contributing to Shakespeare studies with his book Tales From Shakespeare, Lamb also contributed to the popularization of Shakespeare's contemporaries with his book Specimens of the English Dramatic Poets Who Lived About the Time of Shakespeare. Although he did not write his first Elia essay until 1820, Lamb’s gradual perfection of the essay form for which he eventually became famous began as early 1802 in a series of open letters to Leigh Hunt’s Reflector. The most famous of these is called "The Londoner" in which Lamb famously derides the contemporary fascination with nature and the countryside. Legacy Anne Fadiman notes regretfully that Lamb is not widely read in modern times: "I do not understand why so few other readers are clamoring for his company... [he] is kept alive largely through the tenuous resuscitations of university English departments." Lamb was honoured by The Latymer School, a grammar school in Edmonton, a suburb of London where he lived for a time; it has six houses, one of which, "Lamb", is named after Charles. Selected works * Blank Verse, poetry, 1798 * A Tale of Rosamund Gray, and old blind Margaret, 1798 * John Woodvil, poetic drama, 1802 * Tales from Shakespeare, 1807 * The Adventures of Ulysses, 1808 * Specimens of English Dramatic poets who lived about the time of Shakespeare, 1808 * On the Tragedies of Shakespeare, 1811 * Witches and Other Night Fears, 1821 * The Pawnbroker's Daughter, 1825 * Eliana, 1867 * Essays of Elia, 1823 * The Last Essays of Elia, 1833 References Wikipedia – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Lamb