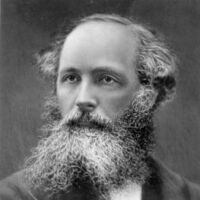

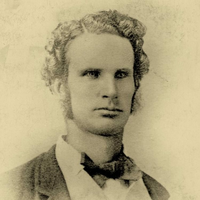

James Clerk Maxwell of Glenlair FRS FRSE (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish physicist and mathematician. His most prominent achievement was formulating classical electromagnetic theory. This unites all previously unrelated observations, experiments, and equations of electricity, magnetism, and optics into a consistent theory. Maxwell's equations demonstrate that electricity, magnetism and light are all manifestations of the same phenomenon, namely the electromagnetic field. Subsequently, all other classic laws or equations of these disciplines became simplified cases of Maxwell's equations. Maxwell's achievements concerning electromagnetism have been called the “second great unification in physics”, after the first one realised by Isaac Newton.

Everyone's entitled to their art; here is mine. Everyone has a lot to process in life and should be able to share the product that results from that construction of meaning. But here it is. Pieces I've written over time and I don't have to tell you explicitly how they all fit together. The whole story is there, but you don't have to understand it like I do. It's for both of us.

Helen Maria Hunt Jackson, born Helen Fiske (October 15, 1830 – August 12, 1885), was a United States writer who became an activist on behalf of improved treatment of Native Americans by the U.S. government. She detailed the adverse effects of government actions in her history A Century of Dishonor (1881). Her novel Ramona dramatized the federal government's mistreatment of Native Americans in Southern California and attracted considerable attention to her cause, although its popularity was based on its romantic and picturesque qualities rather than its political content. It was estimated to have been reprinted 300 times, and contributed to the growth of tourism in Southern California. Early years She was born Helen Fiske in Amherst, Massachusetts, the daughter of Nathan Welby Fiske and Deborah Waterman Vinal. She had two brothers, both of whom died after birth, and a sister Anne. Her father was a minister, author, and professor of Latin, Greek, and philosophy at Amherst College. Her mother died in 1844 when Helen was fourteen, and her father three years later. Her father provided for her education and arranged for an aunt to care for her. Fiske attended Ipswich Female Seminary and the Abbott Institute, a boarding school run by Reverend J.S.C. Abbott in New York City. She was a classmate of the poet Emily Dickinson, also from Amherst. The two corresponded for the rest of their lives, but few of their letters have survived. Marriage and family In 1852 at age 22, Fiske married U.S. Army Captain Edward Bissell Hunt. They had two sons, one of whom, Murray Hunt, died as an infant in 1854 of a brain disease. In 1863, her husband died in a military accident. Her second son, Rennie Hunt, died of diphtheria in 1865. About 1873-1874, Hunt met William Sharpless Jackson, a wealthy banker and railroad executive, while visiting at Colorado Springs, Colorado, at the resort of Seven Falls. They married in 1875 and she took the name Jackson, under which she was best known for her writings. She was a Unitarian. Career Helen Hunt began writing after the deaths of her family members. She published her early work anonymously, usually under the name "H.H." Ralph Waldo Emerson admired her poetry and used several of her poems in his public readings. He included five of them in his anthology Parnassus. She traveled widely. In the winter of 1873-1874 she was in Colorado Springs, Colorado, in search of a cure for tuberculosis. Here she met the man who would become her second husband. Over the next two years, she published three novels in the anonymous No Name Series, including Mercy Philbrick's Choice and Hetty's Strange History. In 1879 her interests turned to Native Americans after hearing a lecture in Boston by the Ponca Chief Standing Bear. He described the forcible removal of the Ponca from their Nebraska reservation and transfer to the Quapaw Reservation in Indian Territory, where they suffered from disease, climate and poor supplies. Upset about the mistreatment of Native Americans by government agents, Jackson became an activist. She started investigating and publicizing government misconduct, circulating petitions, raising money, and writing letters to the New York Times on behalf of the Ponca. A fiery and prolific writer, Jackson engaged in heated exchanges with federal officials over the injustices committed against American Indians. Among her special targets was U.S. Secretary of Interior Carl Schurz, whom she once called "the most adroit liar I ever knew." She exposed the government's violation of treaties with the American Indian tribes. She documented the corruption of US Indian agents, military officers, and settlers who encroached on and stole Indian lands. Jackson won the support of several newspaper editors who published her reports. Among her correspondents were editor William Hayes Ward of the New York Independent, Richard Watson Guilder of the Century Magazine, and publisher Whitelaw Reid of the New York Daily Tribune. Jackson also wrote a book, the first published under her own name, condemning state and federal Indian policy, and detailing the history of broken treaties. A Century of Dishonor (1881) called for significant reform in government policy toward Native Americans.[10] Jackson sent a copy to every member of Congress with a quote from Benjamin Franklin printed in red on the cover: "Look upon your hands: they are stained with the blood of your relations." The New York Times later wrote that she "soon made enemies at Washington by her often unmeasured attacks, and while on general lines she did some good, her case was weakened by her inability, in some cases, to substantiate the charges she had made; hence many who were at first sympathetic fell away." Jackson went to southern California for respite. Having been interested in the area's missions and the Mission Indians on an earlier visit, she began an in-depth study. While in Los Angeles, she met Don Antonio Coronel, former mayor of the city and a well-known authority on early Californio life in the area. He had served as inspector of missions for the Mexican government. Coronel told her about the plight of the Mission Indians after 1833. They were buffeted by the secularization policies of the Mexican government, as well as later U.S. policies, both of which led to their removal from mission lands. Under its original land grants, the Mexican government provided for resident Indians to continue to occupy such lands. After taking control of the territory in 1848, the U.S. generally disregarded such Mission Indian occupancy claims. In 1852, there were an estimated 15,000 Mission Indians in Southern California. By the time of Jackson's visit, they numbered fewer than 4,000. Coronel's account inspired Jackson to action. The U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Hiram Price, recommended her appointment as an Interior Department agent. Jackson's assignment was to visit the Mission Indians, ascertain the location and condition of various bands, and determine what lands, if any, should be purchased for their use. With the help of the US Indian agent Abbot Kinney, Jackson traveled throughout Southern California and documented conditions. At one point, she hired a law firm to protect the rights of a family of Saboba Indians facing dispossession from their land at the foot of the San Jacinto Mountains. In 1883, Jackson completed her 56-page report. It recommended extensive government relief for the Mission Indians, including the purchase of new lands for reservations and the establishment of more Indian schools. A bill embodying her recommendations passed the U.S. Senate but died in the House of Representatives. Jackson decided to write a novel to reach a wider audience. When she wrote Coronel asking for details about early California and any romantic incidents he could remember, she explained her purpose: "I am going to write a novel, in which will be set forth some Indian experiences in a way to move people's hearts. People will read a novel when they will not read serious books."[14] She was inspired by her friend Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852). "If I could write a story that would do for the Indian one-hundredth part what Uncle Tom's Cabin did for the Negro, I would be thankful the rest of my life," she wrote. Although Jackson started an outline in California, she began writing the novel in December 1883 in her New York hotel room, and completed it in about three months. Originally titled In The Name of the Law, she published it as Ramona (1884). It featured Ramona, an orphan girl who was half Indian and half Scots, raised in Spanish Californio society, and her Indian husband Alessandro, and their struggles for land of their own. The characters were based on people known by Jackson and incidents which she had encountered. The book achieved rapid success among a wide public and was popular for generations; it was estimated to have been reprinted 300 times. Its romantic story also contributed to the growth of tourism to Southern California. Encouraged by the popularity of her book, Jackson planned to write a children's story about Indian issues, but did not live to complete it. Her last letter was written to President Grover Cleveland and said: "From my death bed I send you message of heartfelt thanks for what you have already done for the Indians. I ask you to read my Century of Dishonor. I am dying happier for the belief I have that it is your hand that is destined to strike the first steady blow toward lifting this burden of infamy from our country and righting the wrongs of the Indian race." Jackson died of stomach cancer in 1885 in San Francisco, California. Her husband arranged for her burial on a one-acre plot on a high plateau overlooking Colorado Springs, Colorado. Her grave was later moved to Evergreen Cemetery in Colorado Springs. At the time of her death, her estate was valued at $12,642. She used her married names, Helen Hunt and Helen Jackson, but she is most often referred to as Helen Hunt Jackson. The New York Times referred to her as Helen Hunt Jackson in 1885, reporting on her final illness, and in 1886, reporting on visitors to her grave. The name was used during her lifetime by others, though she disliked the practice. "It is not proper to keep one's first married name, after a second marriage", she wrote to Moncure Conway. To Caroline Healey Dall, she admitted she was "positively waging war" against being called "Helen Hunt Jackson". Critical response and legacy Jackson's A Century of Dishonor remains in print, as does a collection of her poetry. A New York Times reviewer said of Ramona that "by one estimate, the book has been reprinted 300 times." One year after Jackson's death the North American Review called Ramona "unquestionably the best novel yet produced by an American woman" and named it, along with Uncle Tom's Cabin, one of two most ethical novels of the 19th century. Sixty years after its publication, 600,000 copies had been sold. There have been over 300 reissues to date and the book has never been out of print. The novel has been adapted for other media, including three films, stage, and television productions. Valery Sherer Mathes assessed the writer and her work: Ramona may not have been another Uncle Tom's Cabin, but it served, along with Jackson's writings on the Mission Indians of California, as a catalyst for other reformers ....Helen Hunt Jackson cared deeply for the Indians of California. She cared enough to undermine her health while devoting the last few years of her life to bettering their lives. Her enduring writings, therefore, provided a legacy to other reformers, who cherished her work enough to carry on her struggle and at least try to improve the lives of America's first inhabitants. Her friend Emily Dickinson once described her limitations: "she has the facts but not the phosphorescence." In a review of a film version, a journalist wrote about the novel, calling it "the long and lugubrious romance by Helen Hunt Jackson, over which America wept unnumbered gallons in the eighties and nineties," and complained of "the long, uneventful stretches of the novel."[26] In reviewing the history of her publisher, Houghton Mifflin, a 1970 reviewer noted that Jackson typified the house's success: "Middle aged, middle class, middlebrow." Jackson herself wrote, "My Century of Dishonor and Ramona are the only things I have done of which I am glad.... They will live, and... bear fruit." A portion of Jackson's Colorado home has been reconstructed in the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum and furnished with her possessions.

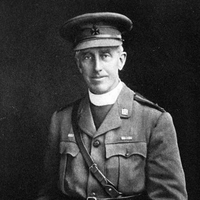

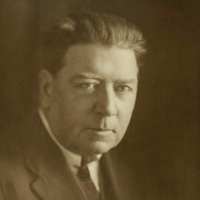

Duncan Campbell Scott (August 2, 1862– December 19, 1947) was a Canadian bureaucrat, poet and prose writer. With Charles G.D. Roberts, Bliss Carman, and Archibald Lampman, he is classed as one of Canada’s Confederation Poets. Scott was a Canadian lifetime civil servant who served as deputy superintendent of the Department of Indian Affairs from 1913 to 1932, and is better known today for advocating the assimilation of Canada’s First Nations peoples in that capacity. Life and legacy Scott was born in Ottawa, Ontario, the son of Rev. William Scott and Janet MacCallum. He was educated at Stanstead Wesleyan College. Early in life, he became an accomplished pianist. Scott wanted to be a doctor, but family finances were precarious, so in 1879 he joined the federal civil service. As the story goes, q:William Scott might not have money [but] he had connections in high places. Among his acquaintances was the prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, who agreed to meet with Duncan. As chance would have it, when Duncan arrived for his interview, the prime minister had a memo on his desk from the Indian Branch of the Department of the Interior asking for a temporary copying clerk. Making a quick decision while the serious young applicant waited in front of him, Macdonald wrote across the request: 'Approved. Employ Mr. Scott at $1.50.’ Scott "spent his entire career in the same branch of government, working his way up to the position of deputy superintendent of Indian Affairs in 1913, the highest non-elected position possible in his department. He remained in this post until his retirement in 1932.” Scott’s father also subsequently found work in Indian Affairs, and the entire family moved into a newly built house on 108 Lisgar St., where Duncan Campbell Scott would live for the rest of his life. In 1883 Scott met fellow civil servant, Archibald Lampman. It was the beginning of an instant friendship that would continue unbroken until Lampman’s death sixteen years later.... It was Scott who initiated wilderness camping trips, a recreation that became Lampman’s favourite escape from daily drudgery and family problems. In turn, Lampman’s dedication to the art of poetry would inspire Scott’s first experiments in verse. By the late 1880s Scott was publishing poetry in the prestigious American magazine, Scribner’s. In 1889 his poems “At the Cedars” and “Ottawa” were included in the pioneering anthology, Songs of the Great Dominion. Scott and Lampman "shared a love of poetry and the Canadian wilderness. During the 1890s the two made a number of canoe trips together in the area north of Ottawa.” In 1892 and 1893, Scott, Lampman, and William Wilfred Campbell wrote a literary column, “At the Mermaid Inn,” for the Toronto Globe. "Scott... came up with the title for it. His intention was to conjure up a vision of The Mermaid Inn Tavern in old London where Sir Walter Raleigh founded the famous club whose members included Ben Jonson, Beaumont and Fletcher, and other literary lights. In 1893 Scott published his first book of poetry, The Magic House and Other Poems. It would be followed by seven more volumes of verse: Labor and the Angel (1898), New World Lyrics and Ballads (1905), Via Borealis (1906), Lundy’s Lane and Other Poems (1916), Beauty and Life (1921), The Poems of Duncan Campbell Scott (1926) and The Green Cloister (1935). In 1894, Scott married Belle Botsford, a concert violinist, whom he had met at a recital in Ottawa. They had one child, Elizabeth, who died at 12. Before she was born, Scott asked his mother and sisters to leave his home (his father had died in 1891), causing a long-time rift in the family. In 1896 Scott published his first collection of stories, In the Village of Viger, "a collection of delicate sketches of French Canadian life. Two later collections, The Witching of Elspie (1923) and The Circle of Affection (1947), contained many fine short stories." Scott also wrote a novel, although it was not published until after his death (as The Untitled Novel, in 1979). After Lampman died in 1899, Scott helped publish a number of editions of Lampman’s poetry. Scott “was a prime mover in the establishment of the Ottawa Little Theatre and the Dominion Drama Festival.” In 1923 the Little Theatre performed his one-act play, Pierre; it was later published in Canadian Plays from Hart House Theatre (1926). His wife died in 1929. In 1931 he married poet Elise Aylen, more than 30 years his junior. After he retired the next year, "he and Elise spent much of the 1930s and 1940s travelling in Europe, Canada and the United States.” He died in December 1947 in Ottawa at the age of 85 and is buried in Ottawa’s Beechwood Cemetery. Indian Affairs Prior to taking up his position as head of the Department of Indian Affairs, in 1905 Scott was one of the Treaty Commissioners sent to negotiate Treaty No. 9 in Northern Ontario. Aside from his poetry, Scott made his mark in Canadian history as the head of the Department of Indian Affairs from 1913 to 1932. Even before Confederation, the Canadian government had adopted a policy of assimilation under the Gradual Civilization Act 1857. One biographer of Scott states that: The Canadian government’s Indian policy had already been set before Scott was in a position to influence it, but he never saw any reason to question its assumption that the 'red’ man ought to become just like the 'white’ man. Shortly after he became Deputy Superintendent, he wrote approvingly: ‘The happiest future for the Indian race is absorption into the general population, and this is the object and policy of our government.’... Assimilation, so the reasoning went, would solve the ‘Indian problem,’ and wrenching children away from their parents to 'civilize’ them in residential schools until they were eighteen was believed to be a sure way of achieving the government’s goal. Scott... would later pat himself on the back: ‘I was never unsympathetic to aboriginal ideals, but there was the law which I did not originate and which I never tried to amend in the direction of severity.’ while Scott himself wrote: I want to get rid of the Indian problem. I do not think as a matter of fact, that the country ought to continuously protect a class of people who are able to stand alone… Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department, that is the whole object of this Bill. In 1920, under Scott’s direction, and with the concurrence of the major religions involved in native education, an amendment to the Indian Act made it mandatory for all native children between the ages of seven and fifteen to attend school. Attendance at a residential school was made compulsory. Although a reading of Bill 14 states that no particular kind of school was stipulated. Scott was in favour of residential schooling for aboriginal children, as he believed removing them from the influences of home and reserve would hasten the cultural and economic transformation of the whole aboriginal population. In cases where a residential school was the only kind available, residential enrollment did become mandatory, and aboriginal children were compelled to leave their homes, their families and their culture, with or without their parents’ consent. However, in 1901, 226 of the 290 Indian schools across Canada were day schools, and by 1961, the 377 day schools far outnumbered the 56 residential institutions. CBC has reported that "In all, about 150,000 aboriginal, Inuit and Métis children were removed from their communities and forced to attend the schools." The 150,000 enrollment figure is an estimate not disputed by Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development, but it is not clear what percentage were “removed from their communities and forced to attend the schools.” A percentage of the residential schools were in or close by the children’s communities. Moreover, while many aboriginal parents distrusted the residential schools or preferred to raise and educate their children in a traditional manner, other parents willingly enrolled their children, partly from a belief that the schooling of the “white man” would benefit them, and partly from a knowledge that schools would provide shelter, food and clothing which dire conditions on the reserve could not provide. Harsh criticism has been leveled at Scott and the residential school system, as children who attended some of the more poorly maintained or administered schools lived in terrible conditions; in some cases the mortality rate exceeded fifty percent due to the spread of infectious disease. This situation was made worse by the federal policy that tied funding to enrollment numbers, which resulted in some schools enrolling sick children in order to boost their numbers. Echoing Scott’s desire to absorb aboriginals into the wider Canadian population, many residential and day schools strongly discouraged students from speaking their native language, and harsh punishments were administered. Corporal punishment was sometimes justified by the belief that it was the only way to “save souls”, “civilize” the native children and, in the residential schools, punish runaways who might make the school responsible for injury or death while trying to return home. Many reports of physical, sexual and psychological abuse in the residential schools have surfaced over the years. Because any kind of scandal coming out of the residential schools would have caused Indian Affairs, the churches and the government of the day much embarrassment, incidents of abuse were often discounted or covered up. When Scott retired, his “policy of assimilating the Indians had been so much in keeping with the thinking of the time that he was widely praised for his capable administration.” At the time, Scott was able to point to evidence of success in increasing enrollment and attendance, as the number of First Nations children enrolled in any school rose from 11,303 in 1912 to 17,163 in 1932. Residential school enrollment during the same period rose from 3,904 to 8,213. Actual attendance figures from all schools had also risen sharply, going from 64% of enrollment in 1920 to 75% in 1930, and Scott attributed this rise partly to Bill 14's section on compulsory attendance but also to a more positive attitude among First Nations people toward education. However, despite the encouraging statistics, Scott’s efforts to bring about assimilation through residential schools could be judged a failure, as many former students retained their language, went on to maintain and preserve their tribe’s culture, and refused to accept full Canadian citizenship when it was offered. Moreover, over the long history of the residential system, only a minority of all enrolled students went beyond the elementary grades, and many former students found themselves lacking the skills that would enable them to find employment on or off the reserve. Honours and awards Scott was honoured for his writing during and after his lifetime. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada in 1899 and served as its president from 1921 to 1922. The Society awarded him the second-ever Lorne Pierce Medal in 1927 for his contributions to Canadian literature. In 1934 he was made a Companion of the Order of St. Michael and St. George. He also received honorary degrees from the University of Toronto (Doctor of Letters in 1922) and Queen’s University (Doctor of Laws in 1939). In 1948, the year after his death, he was designated a Person of National Historic Significance. Poetry Scott’s "literary reputation has never been in doubt. He has been well represented in virtually all major anthologies of Canadian poetry published since 1900.” In Poets of the Younger Generation (1901), Scottish literary critic William Archer wrote of Scott: He is above everything a poet of climate and atmosphere, employing with a nimble, graphic touch the clear, pure, transparent colours of a richly-furnished palette.... Though it must not be understood that his talent is merely descriptive. There is a philosophic and also a romantic strain in it... There is scarcely a poem of Mr. Scott’s from which one could not cull some memorable descriptive passage.... As a rule Mr. Scott’s workmanship is careful and highly finished. He is before everything a colourist. He paints in lines of a peculiar and vivid translucency. But he is also a metrist of no mean skill, and an imaginative thinker of no common capacity. The Government of Canada biography of him says that: Although the quality of Scott’s work is uneven, he is at his best when describing the Canadian wilderness and Indigenous peoples. Although they constitute a small portion of his total output, Scott’s widely recognized and valued 'Indian poems’ cemented his literary reputation. In these poems, the reader senses the conflict that Scott felt between his role as an administrator committed to an assimilation policy for Canada’s Native peoples and his feelings as a poet, saddened by the encroachment of European civilization on the Indian way of life. “There is not a really bad poem in the book,” literary critic Desmond Pacey said of Scott’s first book, The Magic House and Other Poems, “and there are a number of extremely good ones.” The 'extremely good ones’ include the strange, dream-like sonnets of “In the House of Dreams.” “Probably the best known poem from the collection is ‘At the Cedars,’ a grim narrative about the death of a young man and his sweetheart during a log-jam on the Ottawa River. It is crudely melodramatic,... but its style—stark understatement, irregular lines, and abrupt rhymes—makes it the most experimental poem in the book.” His next book, Labour and the Angel, “is a slighter volume than The Magic House in size and content. The lengthy title poem makes dreary reading.... Of greater interest is his growing willingness to experiment with stanza form, variations in line length, use of partial rhyme, and lack of rhyme.” Notable new poems included “The Cup” and the sonnet “The Onandaga Madonna.” But arguably “the most memorable poem in the new collection” was the fantasy, “The Piper of Arll.” One person who long remembered that poem was future British Poet Laureate John Masefield, who read “The Piper of Arll” as a teenager and years later wrote to Scott: I had never (till that time) cared very much for poetry, but your poem impressed me deeply, and set me on fire. Since then poetry has been the one deep influence in my life, and to my love of poetry I owe all my friends, and the position I now hold. New World Lyrics and Ballads (1905) revealed “a voice that is sounding ever more different from the other Confederation Poets... his dramatic power is increasingly apparent in his response to the wilderness and the lives of the people who lived there.” The poetry included “On the Way to the Mission” and the much-anthologized “The Forsaken,” two of Scott’s best-known “Indian poems.” Lundy’s Lane and Other Poems (1916) seemed “to have been cobbled together at the insistence of his publishers, who wanted a collection of his work that had not been published in any previous volume.”. The title poem was one that had won Scott, "in the Christmas Globe contest of 1908,... the prize of one hundred dollars, offered for the best poem on a Canadian historical theme.". Other notable poems in the volume include the pretty lyric “A Love Song,” the long meditation, “The Height of Land,” and the even longer “Lines Written in Memory of Edmund Morris.” Anthologist John Garvin called the last “so original, tender and beautiful that it is destined to live among the best in Canadian literature.” “In his old age, Scott would look back upon Beauty and Life (1921) as his favourite among his volumes of verse," E.K. Brown tells us, adding: “In it most of the poetic kinds he cared about are represented.” There is a great diversity, from the moving war elegy “To a Canadian Aviator Who Died For His Country in France,” to the strange, apocalyptic “A Vision.” The Green Cloister, published after Scott’s retirement, "is a travelogue of the sites he visited in Europe with Elise: Lake Como, Ravelllo, Kensington Gardens, East Gloucester, etc.—descriptive and contemplative poems by an observant tourist. Those with a Canadian setting include two Indian poems of near-melodrama—'A Scene at Lake Manitou’ and 'At Gull Lake, August 1810'—that are in stark contrast to the overall serenity of the volume." More typical is the title poem, “Chiostro Verde.” The Circle of Affection (1947) contains 26 poems Scott had written since Cloister, and several prose pieces, including his Royal Society address on “Poetry and Progress.” It includes “At Delos,” which brings to mind the poet’s approaching death: There is no grieving in the world As beauty fades throughout the years: The pilgrim with the weary heart Brings to the grave his tears. Reputation as an assimilationist In 2003, Scott’s Indian Affairs legacy came under attack from Neu and Therrien: [Scott] took a romantic interest in Native traditions, he was after all a poet of some repute (a member of the Royal Society of Canada), as well as being an accountant and a bureaucrat . He was three people rolled into one confusing and perverse soul. The poet romanticized the whole 'noble savage’ theme, the bureaucrat lamented our inability to become civilized, the accountant refused to provide funds for the so-called civilization process. In other words, he disdained all ‘living’ Natives but “extolled the freedom of the savages”. According to Encyclopædia Britannica, Scott is "best known at the end of the 20th century," not for his writing, but “for advocating the assimilation of Canada’s First Nations peoples.” As part of their Worst Canadian poll, a panel of experts commissioned by Canada’s National History Society named Scott one of the Worst Canadians in the August 2007 issue of The Beaver. In his 2013 Conversations with a Dead Man: The Legacy of Duncan Campbell Scott, fabulist Mark Abley explored the paradoxes surrounding Scott’s career. Abley did not attempt to defend Scott’s work as a bureaucrat, but he showed that Scott is more than simply a one-dimensional villain. Controversy over Arc Poetry prize Arc Poetry Magazine renamed the annual “Archibald Lampman Award” (given to a poet in the National Capital Region) to the Lampman-Scott Award in recognition of Scott’s enduring legacy in Canadian poetry, with the first award under the new name given out in 2007. The winner of the 2008 award, Shane Rhodes, turned over half of the $1,500 prize money to the Wabano Centre for Aboriginal Health, a First Nations health centre. “Taking that money wouldn’t have been right, with what I’m writing about,” Rhodes said. The poet was researching First Nations history and found Scott’s name repeatedly referenced. In the words of a CBC News report, Rhodes felt “Scott’s legacy as a civil servant overshadows his work as a pioneer of Canadian poetry”. The editor of Arc Poetry Magazine, Anita Lahey, responded with a statement that she thought Scott’s actions as head of Indian Affairs were important to remember, but did not eclipse his role in the history of Canadian literature. “I think it matters that we’re aware of it and that we think about and talk about these things,” she said. “I don’t think controversial or questionable activities in the life of any artist or writer is something that should necessarily discount the literary legacy that they leave behind.” More recently, the magazine has stated on its website that "For the years 2007 through 2009, the Archibald Lampman Award merged with the Duncan Campbell Scott Foundation to become the Lampman-Scott Award in honour of two great Confederation Poets. This partnership came to an end in 2010, and the prize returned to its former identity as the Archibald Lampman Award for Poetry.” Publications Poetry * The Magic House and Other Poems. London: Methuen and Co. 1893. - The Magic House and Other Poems at Google Books * Labor and the Angel. Boston: Copeland & Day. 1898. – Labor and the Angel at Google Books– Labor and the Angel - Scholar’s Choice Edition at Google Books * New World Lyrics and Ballads. Toronto: Morang & Co. – New World Lyrics and Ballads at Google Books– New World Lyrics and Ballads - Scholar’s Choice Edition at Google Books * Via Borealis. Toronto: W. Tyrell. 1906. * Lundy’s Lane and Other Poems. Toronto: McClelland, Stewart & Stewart. 1916. - Lundy’s Lane and Other Poems at Google Books * To the Canadian Mothers and Three Other Poems. Toronto: Mortimer. 1917. * “After a Night of Storm” (PDF). Dalhousie Review 1 (2). 1921. * Beauty and Life. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. 1921. - Beauty and Life at Google Books * “Permanence” (PDF). Dalhousie Review 2 (4). 1923. * The Poems of Duncan Campbell Scott. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. 1926. - The Poems of Duncan Campbell Scott at Google Books * “By the Sea” (PDF). Dalhousie Review 7 (1). 1927. * The Green Cloister: Later Poems. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. 1935. - The Green Cloister: Later Poems at Google Books * Brown, E.K., ed. (1951). Selected Poems. Toronto: Ryerson. * Clever, Glenn, ed. (1974). Duncan Campbell Scott: Selected Poetry. Ottawa: Tecumseh. ISBN 978-0-9196-6252-0. * Souster, Raymond; Lochhead, Douglas, eds. (1985). Powassan’s Drum: Selected Poems of Duncan Campbell Scott. Ottawa: Tecumseh. ISBN 978-0-9196-6211-7. Fiction * In the Village of Viger. Boston: Copeland & Day. 1896. - In the Village of Viger at Google Books * The Witching of Elspie: A Book of Stories. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. 1923. * The Circle of Affection and Other Pieces in Prose and Verse. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. 1947. - mostly prose * Clever, Glenn, ed. (1987) [1972]. Selected Stories of Duncan Campbell Scott (revised 3rd ed.). Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press. ISBN 978-0-7766-0183-0. * Untitled Novel (posthumously published). Moonbeam, Ontario: Penumbra. 1979 [c. 1905]. ISBN 0-920806-04-X. * Ware, Tracy, ed. (2001). “The Uncollected Short Stories of Duncan Campbell Scott”. Duncan Campbell Scott. London, Ontario: Canadian Poetry Press. Non-fiction * John Graves Simcoe. Makers of Canada, volume VII. Toronto: Morang & Co. 1905. - John Graves Simcoe at Google Books * The Administration of Indian Affairs in Canada. Volume 3. Toronto: Canadian Institute of International Affairs. 1931. * Walter J. Phillips. Toronto: Ryerson. 1947. - Walter J. Phillips at Google Books * Bourinot, Arthur S., ed. (1960). More Letters of Duncan Campbell Scott. Ottawa: Bourinot. * Davies, Barrie, ed. (1979). At the Mermaid Inn: Wilfred Campbell, Archibald Lampman, Duncan Campbell Scott in the Globe 1892–93. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-6333-5. * Macdougall, Robert L., ed. (1983). The Poet and the Critic: A Literary Correspondence Between Duncan Campbell Scott and E.K. Brown. Ottawa: Carleton University Press. ISBN 978-0-8862-9013-9. Edited * Lampman, Archibald (1900). Scott, Duncan Campbell, ed. The Poems of Archibald Lampman. Toronto: Morang & Co. * Lampman, Archibald (1925). Scott, Duncan Campbell, ed. Lyrics of Earth: Sonnets and Ballads. Toronto: Musson. * Lampman, Archibald (1943). Scott, Duncan Campbell, ed. At the Long Sault and Other New Poems. Toronto: Ryerson. * Lampman, Archibald (1947). Scott, Duncan Campbell, ed. Selected Poems of Archibald Lampman. Toronto: Ryerson. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Duncan_Campbell_Scott

Hi My name is Chyree. I have four children 2 girls 2 boys. After losing their father my husband Joshua in May 2013 to suicide I have found writing poetry a tremendous way to release my feelings. I find it very comforting. I am now engaged to a wonderful man and he inspires my poems now ♥️

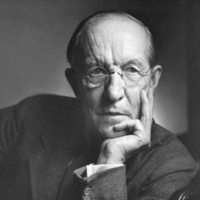

In 1917, Robert Lowell was born into one of Boston's oldest and most prominent families. He attended Harvard College for two years before transferring to Kenyon College, where he studied poetry under John Crowe Ransom and received an undergraduate degree in 1940. He took graduate courses at Louisiana State University where he studied with Robert Penn Warren and Cleanth Brooks. His first and second books, Land of Unlikeness (1944) and Lord Weary's Castle (for which he received a Pulitzer Prize in 1947, at the age of thirty), were influenced by his conversion from Episcopalianism to Catholicism and explored the dark side of America's Puritan legacy. Under the influence of Allen Tate and the New Critics, he wrote rigorously formal poetry that drew praise for its exceptionally powerful handling of meter and rhyme. Lowell was politically involved—he became a conscientious objector during the Second World War and was imprisoned as a result, and actively protested against the war in Vietnam—and his personal life was full of marital and psychological turmoil. He suffered from severe episodes of manic depression, for which he was repeatedly hospitalized. Partly in response to his frequent breakdowns, and partly due to the influence of such younger poets as W. D. Snodgrass and Allen Ginsberg, Lowell in the mid-fifties began to write more directly from personal experience, and loosened his adherence to traditional meter and form. The result was a watershed collection, Life Studies (1959), which forever changed the landscape of modern poetry, much as Eliot's The Waste Land had three decades before. Considered by many to be the most important poet in English of the second half of the twentieth century, Lowell continued to develop his work with sometimes uneven results, all along defining the restless center of American poetry, until his sudden death from a heart attack at age 60. Robert Lowell served as a Chancellor of The Academy of American Poets from 1962 until his death in 1977. Poetry Land of Unlikeness (1944) Lord Weary's Castle (1946) Poems, 1938-1949 (1950) The Mills of the Kavanaughs (1951) Life Studies (1959) Imitations (1961) For the Union Dead (1964) Selected Poems (1965) Near the Ocean (1967) The Voyage and Other Versions of Poems by Baudelaire (1968) Notebooks, 1967-1968 (1969) The Dolphin (1973) For Lizzie and Harriet (1973) History (1973) Selected Poems (1976) Day by Day (1977) Prose The Collected Prose (1987) Anthology Phaedra (1961) Prometheus Bound (1969) Drama The Old Glory (1965) References Poets.org - www.poets.org/poet.php/prmPID/10

#Americans Confessional

Charles Simic (born Dušan Simić; May 9, 1938) is a Serbian-American poet and was co-poetry editor of the Paris Review. He received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1990 for The World Doesn’t End, and was a finalist of the Pulitzer Prize in 1986 for Selected Poems, 1963-1983 and in 1987 for Unending Blues. He was appointed the fifteenth Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress in 2007. Biography Early years Dušan Simić was born in Belgrade. In his early childhood, during World War II, he and his family were forced to evacuate their home several times to escape indiscriminate bombing of Belgrade. Growing up as a child in war-torn Europe shaped much of his world-view, Simic states. In an interview from the Cortland Review he said, “Being one of the millions of displaced persons made an impression on me. In addition to my own little story of bad luck, I heard plenty of others. I’m still amazed by all the vileness and stupidity I witnessed in my life.” Simic immigrated to the United States with his brother and mother in order to join his father in 1954 when he was sixteen. He grew up in Chicago. In 1961 he was drafted into the U.S. Army, and in 1966 he earned his B.A. from New York University while working at night to cover the costs of tuition. He is professor emeritus of American literature and creative writing at the University of New Hampshire, where he has taught since 1973 and lives on the shore of Bow Lake in Strafford, New Hampshire. Career He began to make a name for himself in the early to mid-1970s as a literary minimalist, writing terse, imagistic poems. Critics have referred to Simic’s poems as “tightly constructed Chinese puzzle boxes”. He himself stated: “Words make love on the page like flies in the summer heat and the poet is merely the bemused spectator.” Simic writes on such diverse topics as jazz, art, and philosophy. He is a translator, essayist and philosopher, opining on the current state of contemporary American poetry. He held the position of poetry editor of The Paris Review and was replaced by Dan Chiasson. He was elected to The American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1995, received the Academy Fellowship in 1998, and was elected a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets in 2000. Simic was one of the judges for the 2007 Griffin Poetry Prize and continues to contribute poetry and prose to The New York Review of Books. Simic received the US$100,000 Wallace Stevens Award in 2007 from the Academy of American Poets. He was selected by James Billington, Librarian of Congress, to be the fifteenth Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, succeeding Donald Hall. In choosing Simic as the poet laureate, Billington cited “the rather stunning and original quality of his poetry”. In 2011, he was the recipient of the Frost Medal, presented annually for “lifetime achievement in poetry.” Awards * PEN Translation Prize (1980) * Ingram Merrill Foundation Fellowship (1983) * MacArthur Fellowship (1984–1989) * Pulitzer Prize finalist (1986) * Pulitzer Prize finalist (1987) * Pulitzer Prize for Poetry (1990) * Wallace Stevens Award (2007) * Frost Medal (2011) * Vilcek Prize in Literature (2011) * The Zbigniew Herbert International Literary Award (2014) * Golden Wreath of the Struga Poetry Evenings (2017) Bibliography References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Simic

James Thomson (23 November 1834– 3 June 1882), who wrote under the pseudonym Bysshe Vanolis, was a Scottish Victorian-era poet famous primarily for the long poem The City of Dreadful Night (1874), an expression of bleak pessimism in a dehumanized, uncaring urban environment. Life Thomson was born in Port Glasgow, Scotland, and, after his father suffered a stroke, he was sent to London where he was raised in an orphanage, the Royal Caledonian Asylum on Chalk (later Caledonian after the asylum) Road near Holloway. He spoke with a London accent. He received his education at the Caledonian Asylum and the Royal Military Academy and served in Ireland, where in 1851, at the age of 17, he made the acquaintance of the 18-year-old Charles Bradlaugh, who was already notorious as a freethinker, having published his first atheist pamphlet a year earlier. More than a decade later, Thomson left the military and moved to London, where he worked as a clerk. He remained in contact with Bradlaugh, who was by now issuing his own weekly National Reformer, a “publication for the working man”. For the remaining 19 years of his life, starting in 1863, Thomson submitted stories, essays and poems to various publications, including the National Reformer, which published the sombre poem which remains his most famous work. The City of Dreadful Night came about from the struggle with insomnia, alcoholism and chronic depression which plagued Thomson’s final decade. Increasingly isolated from friends and society in general, he even became hostile towards Bradlaugh. In 1880, nineteen months before his death, the publication of his volume of poetry, The City of Dreadful Night and Other Poems elicited encouraging and complimentary reviews from a number of critics, but came too late to prevent Thomson’s downward slide. Thomson’s remaining poems rarely appear in modern anthologies, although the autobiographical Insomnia and Mater Tenebrarum are well-regarded and contain some striking passages. He admired and translated the works of the pessimistic Italian poet Giacomo Leopardi (1798–1837), but his own lack of hope was darker than that of Leopardi. He is considered by some students of the Victorian age as the bleakest of that era’s poets. He died in London at the age of 47. In 1889, seven years after Thomson’s death, Henry Stephens Salt wrote his first major biography, The Life of James Thomson (B.V.). Thomson’s pseudonym, Bysshe Vanolis, derives from the names of the poets Percy Bysshe Shelley and Novalis. He is often distinguished from the earlier Scottish poet James Thomson by the letters B.V. after the name. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Thomson_(poet,_born_1834)

I love to write. It's as simple a fact as that. In third grade I checked out a large book of poetry and wasn't able to go back from there. Writing poetry became the outlet of the heartache of a young girl as boys broke her fragile heart. Then my "brocuz" killed himself and all those words that I had written previously felt empty. I had changed, and so my poetry changed. Writing is an expression of myself. Whether imagined or real every poem I write, every story, every word, is filled with who I am, and how I got to be who I am. Enjoy :)

Florence Margaret Smith, known as Stevie Smith (20 September 1902– 7 March 1971) was an English poet and novelist. Life Stevie Smith, born Florence Margaret Smith in Kingston upon Hull, was the second daughter of Ethel and Charles Smith. She was called “Peggy” within her family, but acquired the name “Stevie” as a young woman when she was riding in the park with a friend who said that she reminded him of the jockey Steve Donoghue. Her father was a shipping agent, a business that he had inherited from his father. As the company and his marriage began to fall apart, he ran away to sea and Smith saw very little of her father after that. He appeared occasionally on 24-hour shore leave and sent very brief postcards ("Off to Valparaiso, Love Daddy"). When she was three years old she moved with her mother and sister to Palmers Green in North London where Smith would live until her death in 1971. She resented the fact that her father had abandoned his family. Later, when her mother became ill, her aunt Madge Spear (whom Smith called “The Lion Aunt”) came to live with them, raised Smith and her elder sister Molly and became the most important person in Smith’s life. Spear was a feminist who claimed to have “no patience” with men and, as Smith wrote, “she also had 'no patience’ with Hitler”. Smith and Molly were raised without men and thus became attached to their own independence, in contrast to what Smith described as the typical Victorian family atmosphere of “father knows best”. When Smith was five she developed tubercular peritonitis and was sent to a sanatorium near Broadstairs, Kent, where she remained for three years. She related that her preoccupation with death began when she was seven, at a time when she was very distressed at being sent away from her mother. Death and fear fascinated her and provide the subjects of many of her poems. Her mother died when Smith was 16. When suffering from the depression to which she was subject all her life she was so consoled by the thought of death as a release that, as she put it, she did not have to commit suicide. She wrote in several poems that death was “the only god who must come when he is called”. Smith suffered throughout her life from an acute nervousness, described as a mix of shyness and intense sensitivity. In the Poem “A House of Mercy”, she wrote of her childhood house in North London: It was a house of female habitation, Two ladies fair inhabited the house, And they were brave. For although Fear knocked loud Upon the door, and said he must come in, They did not let him in. Smith was educated at Palmers Green High School and North London Collegiate School for Girls. She spent the remainder of her life with her aunt, and worked as private secretary to Sir Neville Pearson with Sir George Newnes at Newnes Publishing Company in London from 1923 to 1953. Despite her secluded life, she corresponded and socialised widely with other writers and creative artists, including Elisabeth Lutyens, Sally Chilver, Inez Holden, Naomi Mitchison, Isobel English and Anna Kallin. After she retired from Sir Neville Pearson’s service following a nervous breakdown she gave poetry readings and broadcasts on the BBC that gained her new friends and readers among a younger generation. Sylvia Plath became a fan of her poetry and sent Smith a letter in 1962, describing herself as “a desperate Smith-addict.” Plath expressed interest in meeting in person but committed suicide soon after sending the letter. Smith was described by her friends as being naive and selfish in some ways and formidably intelligent in others, having been raised by her aunt as both a spoiled child and a resolutely autonomous woman. Likewise, her political views vacillated between her aunt’s Toryism and her friends’ left-wing tendencies. Smith was celibate for most of her life, although she rejected the idea that she was lonely as a result, alleging that she had a number of intimate relationships with friends and family that kept her fulfilled. She never entirely abandoned or accepted the Anglican faith of her childhood, describing herself as a “lapsed atheist”, and wrote sensitively about theological puzzles;"There is a God in whom I do not believe/Yet to this God my love stretches." Her 14-page essay of 1958, “The Necessity of Not Believing”, concludes: “There is no reason to be sad, as some people are sad when they feel religion slipping off from them. There is no reason to be sad, it is a good thing.” Smith died of a brain tumour on 7 March 1971. Her last collection, Scorpion and other Poems was published posthumously in 1972, and the Collected Poems followed in 1975. Three novels were republished and there was a successful play based on her life, Stevie, written by Hugh Whitemore. It was filmed in 1978 by Robert Enders and starred Glenda Jackson and Mona Washbourne. Fiction Smith wrote three novels, the first of which, Novel on Yellow Paper, was published in 1936. Apart from death, common subjects in her writing include loneliness; myth and legend; absurd vignettes, usually drawn from middle-class British life, war, human cruelty and religion. All her novels are lightly fictionalised accounts of her own life, which got her into trouble at times as people recognised themselves. Smith said that two of the male characters in her last book are different aspects of George Orwell, who was close to Smith. There were rumours that they were lovers; he was married to his first wife at the time. Novel on Yellow Paper (Cape, 1936) Smith’s first novel is structured as the random typings of a bored secretary, Pompey. She plays word games, retells stories from classical and popular culture, remembers events from her childhood, gossips about her friends and describes her family, particularly her beloved Aunt. As with all Smith’s novels, there is an early scene where the heroine expresses feelings and beliefs which she will later feel significant, although ambiguous, regret for. In Novel on Yellow Paper that belief is anti-Semitism, where she feels elation at being the “only Goy” at a Jewish party. This apparently throwaway scene acts as a timebomb, which detonates at the centre of the novel when Pompey visits Germany as the Nazis are gaining power. With horror, she acknowledges the continuity between her feeling “Hurray for being a Goy” at the party and the madness that is overtaking Germany. The German scenes stand out in the novel, but perhaps equally powerful is her dissection of failed love. She describes two unsuccessful relationships, first with the German Karl and then with the suburban Freddy. The final section of the novel describes with unusual clarity the intense pain of her break-up with Freddy. Over the Frontier (Cape, 1938) Smith herself dismissed her second novel as a failed experiment, but its attempt to parody popular genre fiction to explore profound political issues now seems to anticipate post-modern fiction. If anti-Semitism was one of the key themes of Novel on Yellow Paper, Over the Frontier is concerned with militarism. In particular, she asks how the necessity of fighting Fascism can be achieved without descending into the nationalism and dehumanisation that fascism represents. After a failed romance the heroine, Pompey, suffers a breakdown and is sent to Germany to recuperate. At this point the novel changes style radically, as Pompey becomes part of an adventure/spy yarn in the style of John Buchan or Dornford Yates. As the novel becomes increasingly dreamlike, Pompey crosses over the frontier to become a spy and soldier. If her initial motives are idealistic, she becomes seduced by the intrigue and, ultimately, violence. The vision Smith offers is a bleak one: “Power and cruelty are the strengths of our lives, and only in their weakness is there love.” The Holiday (Chapman and Hall, 1949) Smith’s final novel is her own favourite, and most fully realised. It is concerned with personal and political malaise in the immediate post-war period. Most of the characters are either employed in the army or civil service in post-war reconstruction, and its heroine, Celia, works for the Ministry as a cryptographer and propagandist. The Holiday describes a series of hopeless relationships. Celia and her cousin Caz are in love, but cannot pursue their affair since it is believed that, because of their parents’ adultery, they are half-brother and sister. Celia’s other cousin Tom is in love with her, Basil is love with Tom, Tom is estranged from his father, Celia’s beloved Uncle Heber, who pines for a reconciliation; and Celia’s best friend Tiny longs for the married Vera. These unhappy, futureless but intractable relationships are mirrored by the novel’s political concerns. The unsustainability of the British Empire and the uncertainty over Britain’s post-war role are constant themes, and many of the characters discuss their personal and political concerns as if they were seamlessly linked. Caz is on leave from Palestine and is deeply disillusioned, Tom goes mad during the war, and it is telling that the family scandal that blights Celia and Caz’s lives took place in India. Just as Pompey’s anti-semitism was tested in Novel on Yellow Paper, so Celia’s traditional nationalism and sentimental support for colonialism is challenged throughout The Holiday. Poetry Smith’s first volume of poetry, the self-illustrated A Good Time Was Had By All, was published in 1937 and established her as a poet. Soon her poems were found in periodicals. Her style was often very dark; her characters were perpetually saying “goodbye” to their friends or welcoming death. At the same time her work has an eerie levity and can be very funny though it is neither light nor whimsical. “Stevie Smith often uses the word 'peculiar’ and it is the best word to describe her effects” (Hermione Lee). She was never sentimental, undercutting any pathetic effects with the ruthless honesty of her humour. “A good time was had by all” itself became a catch phrase, still occasionally used to this day. Smith said she got the phrase from parish magazines, where descriptions of church picnics often included this phrase. This saying has become so familiar that it is recognised even by those who are unaware of its origin. Variations appear in pop culture, including “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!” by the Beatles. Though her poems were remarkably consistent in tone and quality throughout her life, their subject matter changed over time, with less of the outrageous wit of her youth and more reflection on suffering, faith and the end of life. Her best-known poem is “Not Waving but Drowning”. She was awarded the Cholmondeley Award for Poets in 1966 and won the Queen’s Gold Medal for poetry in 1969. She published nine volumes of poems in her lifetime (three more were released posthumously).

Elinor Morton Wylie (September 7, 1885– December 16, 1928) was an American poet and novelist popular in the 1920s and 1930s. “She was famous during her life almost as much for her ethereal beauty and personality as for her melodious, sensuous poetry.” Elinor was born Elinor Morton Hoyt in Somerville, New Jersey, into a socially prominent family. Her grandfather, Henry M. Hoyt, was a governor of Pennsylvania. Her aunt was Helen Hoyt, a minor poet. Her parents were Henry Martyn Hoyt, Jr., who would be United States Solicitor General from 1903 to 1909; and Anne Morton McMichael (born July 31, 1861 in Pa.).