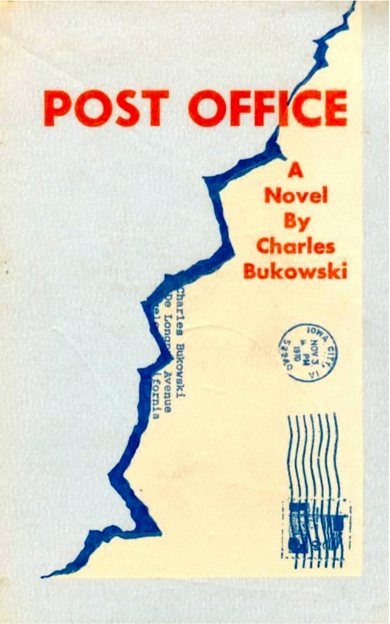

Then I developed a new system at the racetrack. I pulled in $3,000 in a month and a half while only going to the track two or three times a week. I began to dream. I saw a little house down by the sea. I saw myself in fine clothing, calm, getting up

mornings, getting into my imported car, making the slow easy drive to the track. I saw leisurely steak dinners, preceded and followed by good chilled drinks in colored glasses. The big tip. The cigar. And women as you wanted them. It’s easy to fall into this kind of thinking when men handed you large bills at the cashier’s window. When in one six furlong race, say in a minute and 9 seconds, you make a month’s pay.

So I stood in the tour superintendent’s office. There he was behind his desk. I had a cigar in my mouth and whiskey on my breath. I felt like money. I looked like money.

“Mr. Winters,” I said, “the post office has treated me well. But I have outside business interests that simply must be taken care of. If you can’t give me a leave of absence, I must resign.”

“Didn’t I give you a leave of absence earlier in the year, Chinaski?”

“No, Mr. Winters, you turned down my request for a leave of absence. This time there can’t be any turndown. Or I will resign.”

“All right, fill out the form and I’ll sign it. But I can only give you 90 working days off.”

“I’ll take 'em,” I said, exhaling a long trail of blue smoke from my expensive cigar.