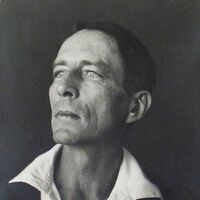

Margrave

On the small marble-paved platform

On the turret on the head of the tower,

Watching the night deepen.

I feel the rock-edge of the continent

Reel eastward with me below the broad stars.

I lean on the broad worn stones of the parapet top

And the stones and my hands that touch them reel eastward.

The inland mountains go down and new lights

Glow over the sinking east rim of the earth.

The dark ocean comes up,

And reddens the western stars with its fog-breath

And hides them with its mounded darkness.

The earth was the world and man was its measure, but our minds

have looked

Through the little mock-dome of heaven the telescope-slotted

observatory eyeball, there space and multitude came in

And the earth is a particle of dust by a sand-grain sun, lost in a

nameless cove of the shores of a continent.

Galaxy on galaxy, innumerable swirls of innumerable stars, endured

as it were forever and humanity

Came into being, its two or three million years are a moment, in

a moment it will certainly cease out from being

And galaxy on galaxy endure after that as it were forever . . .

But man is conscious,

He brings the world to focus in a feeling brain,

In a net of nerves catches the splendor of things,

Breaks the somnambulism of nature . . . His distinction perhaps,

Hardly his advantage. To slaver for contemptible pleasures

And scream with pain, are hardly an advantage.

Consciousness? The learned astronomer

Analyzing the light of most remote star-swirls

Has found them—or a trick of distance deludes his prism—

All at incredible speeds fleeing outward from ours.

I thought, no doubt they are fleeing the contagion

Of consciousness that infects this corner of space.

For often I have heard the hard rocks I handled

Groan, because lichen and time and water dissolve them,

And they have to travel down the strange falling scale

Of soil and plants and the flesh of beasts to become

The bodies of men; they murmur at their fate

In the hollows of windless nights, they’d rather be anything

Than human flesh played on by pain and joy,

They pray for annihilation sooner, but annihilation’s

Not in the book yet.

So, I thought, the rumor

Of human consciousness has gone abroad in the world,

The sane uninfected far-outer universes

Flee it in a panic of escape, as men flee the plague

Taking a city: for look at the fruits of consciousness:

As in young Walter Margrave when he’d been sentenced for

murder: he was thinking when they brought him back

To the cell in jail,

'I’ve only a moment to arrange my thoughts,

I must think quickly, I must think clearly,

And settle the world in my mind before I kick off,' but to feel

the curious eyes of his fellow-prisoners

And the wry-mouthed guard’s and so forth torment him through

the steel bars put his mind in a stupor, he could only

Sit frowning, ostentatiously unafraid. 'But I can control my

mind, their eyes can’t touch my will.

One against all. What use is will at this end of everything? A

kind of nausea is the chief feeling . . .

In my stomach and throat . . . but in my head pride: I fought

a good fight and they can’t break me; alone, unbroken,

Against a hundred and twenty-three million people. They are

going to kill the best brain perhaps in the world,

That might have made such discoveries in science

As would set the world centuries ahead, for I had the mind and

the power. Boo, it’s their loss. Blind fools,

Killing their best.' When his mind forgot the eyes it made rapid

capricious pictures instead of words,

But not of the medical school and the laboratories, its late intense

interest; not at all of his crime; glimpses

Of the coast-range at home; the V of a westward canyon with

the vibrating

Blue line of the ocean strung sharp across it; that domed hill up

the valley, two cows like specks on the summit

And a beautiful-colored jungle of poison-oak at the foot; his

sister half naked washing her hair,

‘My dirty sister,’ whose example and her lovers had kept him

chaste by revulsion; the reed-grown mouth of the river

And the sand-bar against the stinging splendor of the sea...

and anguish behind all the pictures

(He began to consider his own mind again) ‘like a wall they

hang on.’ Hang. The anguish came forward, an actual

Knife between two heartbeats, the organ stopped and then raced.

He experimented awhile with his heart,

Making in his mind a picture of a man hanged, pretending to

himself it was to happen next moment,

Trying to observe whether the beat suspended ‘suspended,’ he

thought in systole or in diastole.

The effect soon failed; the anguish remained. ‘Ah my slack

lawyer, damn him, let slip chance after chance.

Scared traitor.’ Then broken pictures of the scenes in court, the

jury, the judge, the idlers, and not one face

But bleak with hatred. ‘But I met their eyes, one against all.’

Suddenly his mind became incapable

Of making pictures or words, but still wildly active, striking in

all directions like a snake in a fire,

Finding nothing but the fiery element of its own anguish. He got

up and felt the guard’s eyes and sat down,

Turned side-face, resting his chin on his fist, frowning and

trembling. He saw clearly in his mind the little

Adrenal glands perched on the red-brown kidneys, as if all his

doomed tissues became transparent,

Pouring in these passions their violent secretion

Into his blood-stream, raising the tension unbearably. And the

thyroids; tension, tension. A long course of that

Should work grave changes. 'If they tortured a man like a laboratory

dog for discovery: there’d be value gained: but by

process

Of law for vengeance, because his glands and his brain have

made him act in another than common manner:

You incredible breed of asses!' He smiled self-consciously in

open scorn of the people, the guard at the door

To observe that smile 'my God, do I care about the turnkey’s

opinion? ‘suddenly his mind again

Was lashing like a burnt snake. Then it was torpid for a while.

This continued for months.

His father had come to visit him, he saw the ruinous white-haired head

Through two steel wickets under the bluish electric light that

seemed to peel the skin from the face.

Walter said cheerfully too loudly, ’Hullo. You look like a skull.'

The shaven sunk jaws in answer chewed

Inaudible words. Walter with an edge of pleasure thought 'Once

he was stronger than I! I used to admire

This poor old man’s strength when I was a child,' and said 'Buck

up, old fellow, it will soon be over. Here’s nothing

To cry for. Do you think I’m afraid to die? It’s good people that

fear death, people with the soft streak

Of goodness in them fear death: but I, you know, am a monster,

don’t you read the papers? Caught at last:

I fought a hundred and twenty-three million people. How’s

Hazel? How’s the farm? I could get out of this scrape

By playing dementia, but I refuse to, there’s not an alienist living

Could catch me out. I’m the king of Spain dying for the world.

I’ve been persecuted since I was born

By a secret sect, they stuck pins into me

And fed me regular doses of poison for a certain reason. Why

do you pretend that you’re my father?

God is.... Believe me, I could get by with it.

But I refuse.'

Old Margrave looked timidly at the two guards

listening, and drew his brown tremulous hand

Across his eyes below the white hair. ‘I thought of going to try

to see the governor, Walter.’

'That’s it!' 'Don’t hope for anything, Walter, they tell me that

there’s no hope. They say that I shan’t even

Be allowed to see him.' ‘By God,’ the young man said trembling,

'you can if you want to. Never believe that lawyer.

If I’d had Dorking: but you couldn’t afford him. Poor men have

no right to breed sons. I’d not be here

If you’d had money to put me through college. Tell the governor

I know he won’t pardon, but he can commute the sentence to

life imprisonment. Then I can read and study,

I can help the penitentiary doctor, I can do something to help

humanity. Tell him it’s madness

To throw such a brain as mine into the garbage. Don’t deny my

guilt but tell him my reasons.

I kidnapped the little girl to get money to finish my medical

education. What’s one child’s life

Against a career like mine that might have saved

Thousands of children? Say I’d isolated the organism of infantile

paralysis: I’d have done more:

But that alone would save thousands of children. I was merciful;

she died quietly; tell him that.

It was only pithing a little white frog.

Don’t you think you can make him understand? I’m not a criminal:

I judge differently from others. I wasn’t

Afraid to think for myself. All I did

Was for money for my education, to help humanity. And tell

him if I’ve done wrong what’s wrong? I’ve paid for it

With frightful suffering: the more developed the brain the greater

the agony. He won’t admit that. Oh God,

These brains the size of a pea! To be juried

And strangled by a hundred and twenty-three million peas. Go

down on your knees to him. You owe me that: you’d no right

To breed, you’re poor.

But you itched for a woman, you had to fetch me out of the

happy hill of not-being. Pfah, to hug a woman

And make this I. That’s the evil in the world, that letter. I—I—

Tell the governor

That I’m not afraid of dying, that I laugh at death. No, no, we’ll

laugh in private. Tell him I’m crazy.

I’ve come to that: after being the only sane mind among a hundred

and twenty-three million peas.

Anything, anything . . .'

He had let his nerves go wild on purpose,

to edge on the old man to action, now at last

Escaping utterly out of control they stumbled into a bog of thick

sobs. The guards pulled him up

And walked him away as if he were half insensible. He was not

insensible, but more acutely aware

Than ever in his life before of all that touched him, and of shame

and anguish.

You would be wise, you far stars,

To flee with the speed of light this infection.

For here the good sane invulnerable material

And nature of things more and more grows alive and cries.

The rock and water grow human, the bitter weed

Of consciousness catches the sun, it clings to the near stars,

Even the nearer portion of the universal God

Seems to become conscious, yearns and rejoices

And suffers: I believe this hurt will be healed

Some age of time after mankind has died,

Then the sun will say ‘What ailed me a moment?’ and resume

The old soulless triumph, and the iron and stone earth

With confident inorganic glory obliterate

Her ruins and fossils, like that incredible unfading red rose

Of desert in Arizona glowing life to scorn,

And grind the chalky emptied seed-shells of consciousness

The bare skulls of the dead to powder; after some million

Courses around the sun her sadness may pass:

But why should you worlds of the virgin distance

Endure to survive what it were better to escape?

I also am not innocent

Of contagion, but have spread my spirit on the deep world.

I have gotten sons and sent the fire wider.

I have planted trees, they also feel while they live.

I have humanized the ancient sea-sculptured cliff

And the ocean’s wreckage of rock

Into a house and a tower,

Hastening the sure decay of granite with my hammer,

Its hard dust will make soft flesh;

And have widened in my idleness

The disastrous personality of life with poems,

That are pleasant enough in the breeding but go bitterly at last

To envy oblivion and the early deaths of nobler

Verse, and much nobler flesh;

And I have projected my spirit

Behind the superb sufficient forehead of nature

To gift the inhuman God with this rankling consciousness.

But who is our judge? It is likely the enormous

Beauty of the world requires for completion our ghostly increment,

It has to dream, and dream badly, a moment of its night.

On the little stone-belted platform

On the turret on the head of the tower,

Between the stars and the earth,

And the ocean and the continent.

One ship’s light shines and eclipses

Very far out, behind the high waves on the hill of water.

In the east under the Hyades and rising Orion

Are many cities and multitudes of people,

But westward a long way they are few enough.

It is fortunate to look westward as to look upward.

In the south the dark river-mouth pool mirrors a star

That stands over Margrave’s farmhouse. The old man has lost it,

he isn’t there any more. He went down to the river-mouth

Last December, when recent rains had opened the stream and the

salmon were running. Fishermen very solemnly

Stood all along the low sand like herons, and sea-lions offshore

in the rolling waves with deep wet voices

Coughed at each other; the sea air is hoarse with their voices that

time of year. Margrave had rambled since noon

Among the little folds of the seaward field that he had forgotten

to plow and was trying to sell

Though he used to love it, but everything was lost now. He lay

awhile on his face in the rotting stubble and random

Unsown green blades, then he got up and drifted over the ridge

to the river-mouth sands, unaimed,

Pale and gap-eyed, as the day moon a clear morning, opposite the

sun. He noticed with surprise the many

Fishermen like herons in the shallows and along the sands; and

then that his girl Hazel was with him: who’d feared

What he might do to himself and had come to watch him when

he lay face down in the field. 'I know what they’re doing,'

He said slyly, 'Hazel, they’re fishing! I guess they don’t know,'

He whispered, 'about our trouble. Oh no, don’t tell them.' She

said, 'Don’t go down, father, your face would tell them.

Sit here on the edge of grass, watch the brown river meet the

blue sea. Do look: that boy’s caught something.

How the line cuts the water and the small wheel sings.' 'If I’d

been rich,'

Old Margrave answered, 'they’d have fixed the hook for . . .

Walter . . . with some other bait. It sticks in my mind that

. . . Walter

Blames me too much.' ‘Look,’ Hazel said, 'he’s landing it now.

Oh, it’s a big one.' ‘I dreamed about fishing,

Some time ago,’ he answered, 'but we were the fish. I saw the

people all running reaching for prizes

That dangled on long lines from the sky. A lovely girl or a sack

of money or a case of whiskey,

Or fake things like reputation, hackle-feathers and a hook. A man

would reach up and grab and the line

Jerked, then you knew by his face that the hook was in him,

wherever he went. Often they’re played for half

A lifetime before they’re landed: others, like . . . my son . . .

pulled up short. Oh, Oh,

It’s not a dream.' He said gently, 'He wanted money for his

education, but you poor girl

Wanted boy friends, now you’ve got a round belly. That’s the

hook. I wanted children and got

Walter and you. Hm? Hooked twice is too much. Let’s walk.'

'Not that way: let’s go up home, daddy.

It makes you unhappy to see them fishing.' ‘No,’ he answered,

‘nothing can. I have it in my pocket.’ She walked behind him,

Hiding herself, ashamed of her visible pregnancy and her brother’s

fate; but when the old man stumbled

And wavered on the slope she went beside him to support him,

her right hand under his elbow, and wreathed his body

With the other arm.

The clear brown river ran eagerly through

the sand-hill, undercutting its banks,

That slid in masses; tall waves walked very slowly up stream from

the sea, and stood

Stationary in the throat of the channel before they dissolved. The

rock the children call Red-cap stood

High and naked among the fishermen, the orange lichen on its

head. At the sea-end of the sand

Two boys and a man had rifles instead of rods, they meant to

punish the salmon-devouring sea-lions

Because the fish were fewer than last year; whenever a sleek

brown head with the big questioning eyes

Broke sea they fired. Margrave had heard the shots but taken no

notice, but when he walked by the stream

He saw a swimmer look up from the water and its round dark eye

Suddenly burst red blood before it went down. He cried out and

twisted himself from Hazel’s hand

And ran like a squirrel along the stream-bank. 'I’ll not allow it!'

He snatched at a rifle. ‘Why should my lad

Be hanged for killing and all you others go free?’ He wrestled

feebly to gain the rifle, the sand-bank

Slid under his feet, he slipped and lay face down in the running

stream and was hauled astrand. Then Hazel

Came running heavily, and when he was able to walk she led him

away. The sea-beast, blinded but a painful

Vain gleam, starved long before it could die; old Margrave still

lives. Death’s like a little gay child that runs

The world around with the keys of salvation in his foolish fingers,

lends them at random where they’re not wanted,

But often withholds them where most required.

Margrave’s son

at this time

Had only four days to wait, but death now appeared so dreadful

to him that to speak of his thoughts and the abject

Horror, would be to insult humanity more than it deserves. At

last the jerked hemp snapped the neck sideways

And bruised the cable of nerves that threads the bone rings; the

intolerably strained consciousness in a moment changed.

It was strangely cut in two parts at the noose, the head’s

Consciousness from the body’s; both were set free and flamed;

the head’s with flashing paradisal light

Like the wild birth of a star, but crying in bewilderment and

suddenly extinguished; the body’s with a sharp emotion

Of satisfied love, a wave of hard warmth and joy, that ebbed cold

on darkness. After a time of darkness

The dreams that follow upon death came and subsided, like

fibrillar twitchings

Of the nerves unorganizing themselves; and some of the small

dreams were delightful and some, slight miseries,

But nothing intense; then consciousness wandered home from the

cell to the molecule, was utterly dissolved and changed;

Peace was the end of the play, so far as concerns humanity. Oh

beautiful capricious little savior,

Death, the gay child with the gipsy eyes, to avoid you for a time

I think is virtuous, to fear you is insane.

On the little stone-girdled platform

Over the earth and the ocean

I seem to have stood a long time and watched the stars pass.

They also shall perish I believe.

Here to-day, gone to-morrow, desperate wee galaxies

Scattering themselves and shining their substance away

Like a passionate thought. It is very well ordered.