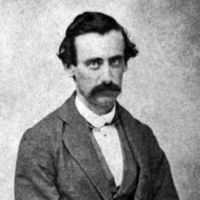

Henry Timrod

Henry Timrod (December 8, 1829– October 7, 1867) was an American poet, often called the poet laureate of the Confederacy.

Henry Timrod (December 8, 1829– October 7, 1867) was an American poet, often called the poet laureate of the Confederacy.

Early life

Timrod was born on December 8, 1829, in Charleston, South Carolina, to a family of German descent. His grandfather Heinrich Dimroth emigrated to the United States in 1765 and anglicized his name. His father, William Henry Timrod, was an officer in the Seminole Wars and a poet himself. In fact, he composed the following poem on the subject of his eldest son, Henry:

I love to have thee playing near;

There’s music in thy shouts of joy,

To a fond father’s ear.

Mantle thy cheeks and forehead fair,

As if all the pleasures of the earth

Had met to revel there.

That those most happy years must flee;

And thy full share of misery

Must fall in life on thee.

The elder Timrod died from tuberculosis on July 28, 1838, in Charleston, at the age of 44, leaving behind his wife of 25 years, Thyrza Prince Timrod, and their four children, the eldest of which was Adaline Rebecca, 14 years; Henry was nine. A few years later, their home burned down, leaving the family impoverished.

He studied at the University of Georgia beginning in 1847 with the help of a financial benefactor. He was soon forced by illness to end his formal studies, however, and returned to Charleston. He took a position with a lawyer and planned to begin a law practice. From 1848 to 1853, he submitted a number of poems to the Southern Literary Messenger under the pen name Aglaus, where he attracted some attention for his abilities. He left his legal studies by December 1850, calling it “distasteful”, and focused more on writing and tutoring. He was a member of Charleston’s literati, and with John Dickson Bruns and Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve, could often be found in the company of their leader, William Gilmore Simms, whom they referred to as “Father Abbot,” from one of his novels.

Career

In 1856, he accepted a post as a teacher at the plantation of Colonel William Henry Cannon in the area that would later become Florence, South Carolina. Cannon had a single-room school building built in 1858 to provide for the education of the plantation children. The building measures “only about twelve by fifteen feet in size.” Among his students was the young lady who would later become his bride and the object of a number of his poems– the “fair Saxon” Kate Goodwin. These lines from “Katie”, the opening poem of The Poems of Henry Timrod (1873), are an example:

With music brims the cup of morn,

And in a thick, melodious rain

The mavis pours her mellow strain!

But only when my Katie’s voice

Makes all the listening woods rejoice

I hear—with cheeks that flush and pale—

The passion of the nightingale!

While teaching and tutoring, he continued also to publish his poems in literary magazines. In 1860, he published a small book, which, although a commercial failure, increased his fame. The best-known poem from the book was “A Vision of Poesy”.

Civil War period

With the outbreak of American Civil War, in a state of fervent patriotism, Timrod returned to Charleston to begin publishing his war poems, which drew many young men to enlist in the service of the Confederacy. His first poem of this period is “Ethnogenesis”, written in February, 1861, during the meeting of the first Confederate Congress at Montgomery, Alabama. Part of the poem was read aloud at this meeting:

And shall not evening call another star

Out of the infinite regions of the night

To mark this day in Heaven? At last we are

A nation among nations. And the world

Shall soon behold in many a distant port

Another flag unfurled!

“A Cry to Arms”, “Carolina” and “The Cotton Boll” are other famous examples of his martial poetry. He was a frequent contributor of poems to Russell’s Magazine and to The Southern Literary Messenger.

On March 1, 1862, Timrod enlisted into the military as a private in Company B, 30th South Carolina Regiment, and was detailed for special duty as a clerk at regimental headquarters, but his tuberculosis prevented much service, and he was sent home. After the bloody Battle of Shiloh, he tried again to live the camp life as a western war correspondent for the Charleston Mercury, but this too was short lived as he was not strong enough for the rugged task.

He returned from the front and settled in Columbia, South Carolina, to become associate editor of the South Carolinian, a daily newspaper. Throughout 1864 he wrote many articles for the paper. In February 1864 he married his beloved Katie, and they soon had a son, Willie, born on Christmas Eve.

This happy period in his life was short-lived. General Sherman’s troops invaded Columbia on February 17, 1865, one year and one day after his marriage. Due to the vigor of his editorials, he was forced into hiding, his home was burned, and the newspaper office was destroyed.

Death

The aftermath of war brought his family poverty and to him and his wife, increasing illness. He moved his family into his sister and mother’s home in Columbia. Then, his son Willie died on October 23, 1865. He expressed his sorrow in the poem “Our Willie”:

Our little boy beneath the sod;

And brighter burned the Christmas flame,

And merrier sped the game

Because within the house there lay

A shape as tiny as a fay—

The Christmas gift of God!

He took a post as correspondent for a new newspaper based in Charleston, The Carolinian, but continued to reside in Columbia. Even after several months of work, however, he was never paid, and the paper folded. In economic desperation, he submitted poems written in his strongest style to northern periodicals, but all were coldly declined. Henry continued to seek work, but continued to be disappointed. Finally, in November, 1866, he was given an assistant clerkship under Governor James L. Orr’s staff member James S. Simons. This lasted less than a month, after which he was again dependent on charity and odd jobs to feed his family of women. Despite the harshly reduced circumstances, and mounting health problems, he was still able to produce highly regarded poetry. His “Memorial Ode”, composed in the Spring of 1867 “was sung at Magnolia Cemetery, Charleston, in May when the graves of the southern dead were decorated.”

Sleep, martyrs of a fallen cause;

Though yet no marble column craves

The pilgrim here to pause.

The blossom of your flame is blown,

And somewhere, waiting for its birth,

The shaft is in the stone!

Which keep in trust your storied tombs,

Behold! Your sisters bring their tears,

And these memorial blooms.

He finally succumbed to consumption Sunday morning, October 7, 1867, and was laid to rest in the churchyard at Trinity Episcopal Church in Columbia next to his son.

Criticism and legacy

Timrod’s friend and fellow poet, Paul Hamilton Hayne, posthumously edited and published The Poems of Henry Timrod, with more of Timrod’s more famous poems in 1873, including his "Ode: Sung on the Occasion of Decorating the Graves of the Confederate Dead at Magnolia Cemetery, Charleston, S.C., 1867" and “The Cotton Boll”.

Later critics of Timrod’s writings, including Edd Winfield Parks and Guy A. Cardwell, Jr. of the University of Georgia, Jay B. Hubbell of Vanderbilt University and Christina Murphy, who completed a Ph.D. dissertation on Timrod at the University of Connecticut, have asserted that Timrod was one of the most important regional poets of nineteenth-century America and one of the most important Southern poets. In terms of achievement, Timrod is often compared to Sidney Lanier and John Greenleaf Whittier as poets who achieved significant stature by combining lyricism with a poetic capacity for nationalism. All three poets also explored the heroic ode as a poetic form.

Today, Timrod’s poetry is included in most of the historical anthologies of American poetry, and he is regarded as a significant-though secondary-figure in 19th-century American literature.

In 1901, a monument with a bronze bust of Timrod was dedicated in Charleston. The state’s General Assembly passed a resolution in 1911 instituting the verses of his poem “Carolina” as the lyrics of the official state anthem.

In September 2006, an article for The New York Times noted similarities between Bob Dylan’s lyrics in the album, Modern Times and the poetry of Timrod. A wider debate developed in The Times as to the nature of “borrowing” within the folk tradition and in literature.

References

Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Timrod