Thy fingers make early flowers of all things

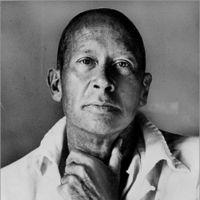

Rushworth M. Kidder (1979)

..."Thy fingers make early flowers of," is justified [for inclusion in the "Songs" sequence] by a graceful lyricism built from the literary counterparts of musical devices. Theme and variation...refrain...and a careful attention to rhyme mark the piece as more song than statement. Employing a free-verse cadence within a rather tight structure, Cummings draws his effects both from accentual verse, as in the repeated spondees in the third line of each stanza, and from syllabic verse, as the common measure of the second, fourth, and fifth lines in each stanza demonstrates. In substance, the carpe diem argument to his lady depends on a simple repetition of motifs: praise of "Thy fingers" and "thy hair" in stanza one parallels praise of "thy whitest feet" and "thy moist eyes" in stanza two. The last stanza focuses on "thy lips," noting that Death, even if it misses everything else, is rich if it catches them. The lyric ends with just enough ambiguity to give it a nutty solidity: the lines "(though love be a day / and life be nothing, it shall not stop kissing)" leave unresolved the antecedent for "it," which may be love, life, or Death. In any case, nothing elevates the lover’s intentions here: body is all, kissing is the goal, and promiscuity ("for which girl art thou flowers bringing?" she asks) is the order of the day.

From Rushworth M. Kidder, E. E. Cummings: An Introduction to the Poetry (New York: Columbia UP, 1979): 22''Barry A. Marks (1964)'''

One early effort, "Thy fingers make early flowers of all things"... varies from the traditional carpe diem poem so slightly that it almost escapes notice. Much of its special tenderness...results from Cummings' having reversed the usual male-female roles. The maiden is a coquette, but her intentions are far more openly dishonorable than those of her seventeenth-century sisters. Far from putting her suitor off, she is gently leading him out of his fearful preoccupation with life's evanescence, encouraging him to put his whole heart into his kissing. "listen/ beloved/ i dreamed"... presents the male speaker subtly but traditionally threatening his lady. But here archaic and modern colloquial diction intermix, and the apparently traditional imagery communicates with special force through its association with fantastic Freudian dream material.

From Barry Marks, E. E. Cummings (New York: Twayne, 1964), 68-69.