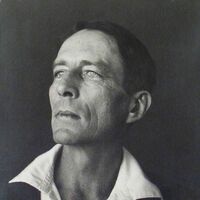

A Redeemer

The road had steepened and the sun sharpened on the high

ridges; the stream probably was dry,

Certainly not to be come to down the pit of the canyon. We

stopped for water at the one farm

In all that mountain. The trough was cracked with drought, the

moss on the boards dead, but an old dog

Rose like a wooden toy at the house-door silently. I said ‘There

will be water somewhere about,’

And when I knocked a man showed us a spring of water. Though

his hair was nearly white I judged him

Forty years old at most. His eyes and voice were muted. It is

likely he kept his hands hidden,

I failed to see them until we had dipped the spring. He stood then

on the lip of the great slope

And looked westward over an incredible country to the far hills

that dammed the sea-fog: it billowed

Above them, cascaded over them, it never crossed them, gray

standing flood. He stood gazing, his hands

Were clasped behind him; I caught a glimpse of serous red under

the fingers, and looking sharply

When they drew apart saw that both hands were wounded. I said

‘Your hands are hurt.’ He twitched them from sight,

But after a moment having earnestly eyed me displayed them.

The wounds were in the hearts of the palms,

Pierced to the backs like stigmata of crucifixion. The horrible

raw flesh protruded, glistening

And granular, not scabbed, nor a sign of infection. ‘These are

old wounds.’ He answered, 'Yes. They don’t heal.' He stood

Moving his lips in silence, his back against that fabulous basin

of mountains, fold beyond fold,

Patches of forest and scarps of rock, high domes of dead gray

pasture and gray beds of dry rivers,

dear and particular in die burning air, too bright to appear real,

to the last range

The fog from the ocean like a stretched compacted thunderstorm

overhung; and he said gravely:

'I pick them open. I made them long ago with a clean steel. It

is only a litde to pay’

He stretched and flexed the fingers, I saw his sunburnt lips whiten

in a line, compressed together,

‘If only it proves enough for a time to save so many.’ I

searched his face for madness but that

Is often invisible, a subtle spirit. ‘There never,’ he said, ‘was

any people earned so much ruin.

I love them, I am trying to suffer for them. It would be bad if

I should die, I am careful

Against excess.’ ‘You think of the wounds,’ I said, ‘of Jesus?’

He laughed angrily and frowned, stroking

The fingers of one hand with the other. 'Religion is the people’s

opium. Your little Jew-God?

My pain,' he said with pride, 'is voluntary.

They have done what never was done before. Not as a people

takes a land to love it and be fed,

A little, according to need and love, and again a little; sparing

the country tribes, mixing

Their blood with theirs, their minds with all the rocks and rivers,

their flesh with the soil: no, without hunger

Wasting the world and your own labor, without love possessing,

not even your hands to the dirt but plows

Like blades of knives; heartless machines; houses of steel: using

and despising the patient earth . . .

Oh, as a rich man eats a forest for profit and a field for vanity,

so you came west and raped

The continent and brushed its people to death. Without need,

the weak skirmishing hunters, and without mercy.

Well, God’s a scarecrow; no vengeance out of old rags. But

there are acts breeding their own reversals

In their own bellies from the first day. I am here’ he saidand

broke off suddenly and said ‘They take horses

And give them sicknesses through hollow needles, their blood

saves babies: I am here on the mountain making

Antitoxin for all the happy towns and farms, the lovely blameless

children, the terrible

Arrogant cities. I used to think them terrible: their gray prosperity,

’their pride: from up here

Specks of mildew.

But when I am dead and all you with whole

hands think of nothing but happiness,

Will you go mad and kill each other? Or horror come over

the ocean on wings and cover your sun?

I wish,' he said trembling, ‘I had never been born.’

His wife came from the door while he was talking. Mine asked

her quietly, ‘Do you live all alone here,

Are you not afraid?’ ‘Certainly not,’ she answered, 'he is

always gentle and loving. I have no complaint

Except his groans in the night keep me awake often. But when

I think of other women’s

Troubles: my own daughter’s: I’m older than my husband, I

have been married before: deep is my peace.'