I had to fly to Illinois to give a reading at the University. I hated readings, but they helped with the rent and maybe they helped sell books. They got me out of east Hollywood, they got me up in the air with the businessmen and the stewardesses and the iced drinks and little napkins and the peanuts to kill the breath.

I was to be met by the poet, William Keesing, who I had been corresponding with since 1966. I had first seen his work in the pages of Bull, edited by Doug Fazzick, one of the first mimeo mags and probably the leader in the mimeo revolution. None of us were literary in the proper sense: Fazzick worked in a rubber plant, Keesing was an ex-Marine out of Korea who had done time and was supported by his wife, Cecelia. I was working 11 hours a night as a postal clerk. That was also the time when Marvin arrived on the scene with his strange poems about demons. Marvin Woodman was the best damned demon-writer in America. Maybe in Spain and Peru too. I was into writing letters at the time. I wrote 4 and 5 page letters to everybody, coloring the envelopes and pages wildly with crayons. That’s when I began writing William Keesing, ex-Marine, ex-con, drug addict (he was mostly into codeine).

Now, years later, William Keesing had secured a temporary teaching job at the University. He had managed to pick up a degree or two between drug busts. I warned him that it was a dangerous job for anybody who wanted to write. But at least he taught his class plenty of Chinaski.

Keesing and his wife were waiting at the airport. I had my baggage with me and so we went right to the car. “My God,” said Keesing, “I never saw anybody get off of an airplane looking like that.”

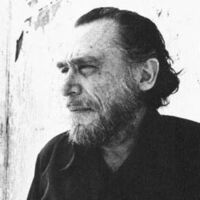

I had on my dead father’s overcoat, which was too large. My pants were too long, the cuffs came down over the shoes and that was good because my stockings didn’t match, and my shoes were down at the heels. I hated barbers so I cut my own hair when I couldn’t get a woman to do it. I didn’t like to shave and I didn’t like long beards, so I scissored myself every two or three weeks. My eyesight was bad but I didn’t like glasses so I didn’t wear them except to read. I had my own teeth but not that many. My face and my nose were red from drinking and the light hurt my eyes so I squinted through tiny slits. I would have fit into any skid row anywhere.

We drove off.

“We expected somebody quite different,” said Cecelia.

“Oh?”

“I mean, your voice is so soft, and you seem gentle. Bill expected you to get off the plane drunk and cursing, making passes at the women. ...”

“I never pump up my vulgarity. I wait for it to arrive on its own terms.” “You’re reading tomorrow night,” said Bill.

“Good, we’ll have fun tonight and forget everything.”

We drove on.

That night Keesing was as interesting as his letters and poems. He had the good sense to stay away from literature in our conversation, except now and then. We talked about other things. I didn’t have much luck in person with most poets even when their letters and poems were good. I’d met Douglas Fazzick with less than charming results. It was best to stay away

from other writers and just do your work, or just not do your work.

Cecelia retired early. She had a job to go to in the morning. “Cecelia is divorcing me,” Bill told me. “I don’t blame her. She’s sick of my drugs, my puke, my whole thing. She’s stood it for years. Now she can’t take it any longer. I can’t give her much of a fuck anymore. She’s running with this teenage kid. I can’t blame her. I’ve moved out, I’ve got a room. We can go there and sleep or I can go there and sleep and you can stay here or we both can stay here, it doesn’t matter to me.”

Keesing took out a couple of pills and dropped them. “Let’s both stay here,” I said.

“You really pour the drinks down.”

“There’s nothing else to do.”

“You must have a cast-iron gut.”

“Not really. It busted open once. But when those holes grow back together they say it’s tougher than the best welding.”

“How long you figure to go on?” he asked.

“I’ve got it all planned. I’m going to die in the year 2000 when I’m 80.”

“That’s strange,” said Keesing, "That’s the year I’m going to die. 2000. I even had a dream about it. I even dreamed the day and hour of my death. Anyhow, it’s in the year 2000.”

“It’s a nice round number. I like it.”

We drank for another hour or two. I got the extra bedroom. Keesing slept on the couch. Cecelia apparently was serious about dumping him.

The next morning I was up at 10:30 am. There was some beer left. I managed to get one down. I was on the second when Keesing walked in.

“Jesus, how do you do it? You spring back like an 18 year old boy." “I have some bad mornings. This just isn’t one.”

“I’ve got a 1:00 English class. I’ve got to get straight.”

“Drop a white.”

“I need some food in my gut.”

“Eat two soft-boiled eggs. Eat them with a touch of chili powder or paprika.”

“Can I boil you a couple?”

“Thanks, yes.”

The phone rang. It was Cecelia. Bill talked a while, then hung up. “There’s a tornado approaching. One of the biggest in the history of the state. It might come through here.”

“Something always happens when I read.”

I noticed it was beginning to get dark.

“They might cancel the class. It’s hard to tell. I better eat.”

Bill put the eggs on.

“I don’t understand you,” he said, “you don’t even look hung-over.”

“I’m hungover every morning. It’s normal. I’ve adjusted.”

“You’re still writing pretty good shit, in spite of all that booze.”

“Let’s not get on that. Maybe it’s the variety of pussy. Don’t boil those eggs too long.”

I went into the bathroom and took a shit. Constipation wasn’t one of my problems. I was just coming out when I heard Bill holler, “Chinaski!”

Then I heard him in the yard, he was vomiting. He came back. The poor guy was really sick.

“Take some baking soda. You got a Valium?”

“No.”

“Then wait 10 minutes after the baking soda and drink a warm beer. Pour it in a glass now so the air can get to it.”

“I got a bennie.”

“Take it.”

It was getting darker. Fifteen minutes after the bennie Bill took a shower. When he came out he looked all right. He ate a peanut butter sandwich with sliced banana. He was going to make it.

“You still love your old lady, don’t you?” I asked.

“Christ, yes.”

“I know it doesn’t help, but try to realize that it’s happened to all of us, at least once.”

“That doesn’t help.”

“Once a woman turns against you, forget it. They can love you, then something turns in them. They can watch you dying in a gutter, run over by a car, and they’ll spit on you.”

“Cecelia’s a wonderful woman.”

It was getting darker. “Let’s drink some more beer,” I said.

We sat and drank beer. It got really dark and then there was a high wind. We didn’t talk much. I was glad we had met. There was very little bullshit in him. He was tired, maybe that helped. He’d never had any luck with his poems in the U.S.A. They loved him in Australia. Maybe some day they’d discover him here, maybe not. Maybe by the year 2000. He was a tough, chunky little guy, you knew he could duke it, you knew he had been there. I was fond of him.

We drank quietly, then the phone rang. It was Cecelia again. The tornado had passed over, or rather, around. Bill was going to teach his class. I was going to read that night. Bully. Everything was working. We were all fully employed.

About 12:30 pm Bill put his notebooks and whatever he needed into a backpack, got on his bike and pedaled off to the university.

Cecelia came home sometime in the mid-afternoon. “Did Bill get off all right?” “Yes, he left on the bike. He looked fine.”

“How fine? Was he on shit?” “He looked fine. He ate and everything.” “I still love him, Hank. I just can’t go through it anymore.” “Sure.”

“You don’t know how much it means to him to have you out here. He used to read your letters to me.” “Dirty, huh?”

“No, funny. You made us laugh.” “Let’s fuck, Cecelia.” “Hank, now you’re playing your game.” “You’re a plump little thing. Let me sink it in.” “You’re drunk, Hank.” “You’re right. Forget it.”