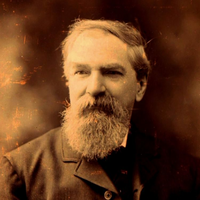

PARTLY from deference to the opinion of a few well-wishers, and partly from an impression that it would be proper so to do, I beg leave to state that the author of the following Lyrics is a coal-miner, and that he was sent into the coal pits of Percy Main, near North Shields, to help to earn his bread while yet a mere child, and when the sum total of his learning consisted in his ability to read his A.B.C., or at most his A. B. ab card. When it is stated that the requirements of the times at that period necessitated the young to be in the mines from twelve to fourteen hours her day, it will be seen that they had little leisure for self-culture, and that only by dint of perseverance, and by not allowing the few spare moments to remain un-utilized that should present themselves, could those who had a desire, acquire anything in the shape of education. The author being possessed with the requisite aspiration, soon had felt what is thus expressed, and instead of spending his hours on the play-ground, he devoted his Sundays and other holidays to the acquisition of the ability to read, and to decipher simple arithmetical questions. These operations were usually performed in his mother’s garret, (he had no father—the father having lost his life when the writer was a baby “in arms”) whilst he learned himself to write with a piece, of chalk on his trap-door—a door connected with the ventilation of the mine, and which it was his duty to attend. In this rude way were his studies pursued, and with what success may be indicated by the fact, that before he was eleven years old, he had formed the romantic notion of trying to commit the Bible to memory, and that he had actually acquired a number of the chapters by “heart,” and was only prevented from proceeding further by the redicule of a grey-bearded wiseacre to whom he had had the temerity to disclose his project. By the time he was sixteen years old, he had from a Lindley Murray which had been presented to him by an aunt, and through much effort and perseverance, acquired a knowledge of the elements of English Grammar. Other studies chiefly of a scientific nature succeeded this—then that of poetry—or rather the poetry of celebrated poets, as Shakspere, Milton, and Burns, for otherwise the love of the muses had grown up with him from his infancy, and he had actually practised verse-making, while he was yet a child behind his trap-door.

After the elapse of a few more years, and after making repeated efforts and in vain to get a suitable situation out of the mines, he printed a batch of lyrics (1859), which earned him the respect of several eminent persons in the North of England. Through the kindness of one of these he was placed into the office of sub-store-keeper at The Gateshead Iron Works. This was at the commencement of the year 1859, and at the latter part of the year 1863 he was placed, on the commendation of the same kind friend, as sub-librarian to the Literary and Philosophical Society, Newcastle-upon-Tyne. This latter office, which was certainly extremely congenial to his tastes, he only held a few months, when from the inadequacy of the income to meet his domestic needs he was necessitated to it give it up, again to find himself a toiler in the coal mines. In 1871 he again resorted to the printer, and issued a small volume of poems, which obtained a kindly notice not only from the Newcastle Chronicle and the rest of the local papers, but also from many of the London weeklies, including the Literary World and the Sunday Times, and also a kind word from the Athenæum and the Spectator; whilst several of the pieces included in this issue were honoured by a translation into the French tongue and published in the Beautés de la Poësie de Anglaise par le Chevalier De Chatelain. The encouragement thus received has helped to stimulate the author to persevere in his attempts at self-culture, and the embodiment, when the impulse has come upon him, of his sentiments and feelings in verse, until he finds himself in possession of material for the present book—a book which he now submits to the public in the hope that it may at once prove of some interest to the peruser, and be the means of rendering some little personal benefit to himself.In conclusion, the author would say, that should the present venture, several of the Pieces of which have already seen the light, find favour with the public, it may in due time be succeeded by a companion volume—a book of Songs and Ditties, and in the two brochures thus offered, would be comprised nearly the whole of his verse that the author would care to put into print.