Suzanne

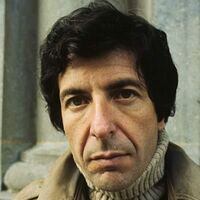

Suzanne Verdal McCallister interviewed by Kate Saunders Transcription from tape by Marie Mazur Narrator: Now, "You Probably Think This Song Is about You" and a trip back to the early 60’s in Montreal to meet a young dancer married to Armand, a handsome sculptor. She became the muse of dozens of Beat poets but for one, Leonard Cohen, she became extra special.

Suzanne takes you down

to her place near the river

you can hear the boats go by

you can spend the night beside her

And you know she’s half crazy

Suzanne: The Beat scene was beautiful. It was live jazz and we were just dancing our hearts out for hours on end, happy on very little. I mean we were living, most of us, on a shoestring. Yet, there was always so much to go around, if you know what I mean. You know, there was so much energy and sharing and inspiration and pure moments and quality times together on very little or no money.

Saunders: Do you remember exactly when you met Leonard Cohen? Where were you that night, do you remember?

Suzanne: It was maybe several months into my relationship with Armand, which was mostly based on being dancing partners together. And he would watch us dancing, of course. And then I was introduced to Leonard at Le Vieux Moulin, I think in the presence of Armand, in fact. But we didn’t really strike a note together until maybe three or four years later.

Saunders: So Leonard Cohen saw you when you were a young girl in love?

Suzanne: Oh very much so. He got such a kick out of seeing me emerge as a young schoolgirl I suppose, and a young artist, into becoming Armand’s lover and then wife. So, he was more or less chronicling the times and seemingly got a kick out of it (laughs).

Saunders: When did you then strike up this friendship that Leonard Cohen describes in song?

Suzanne: With Leonard, it happened more in the beginning of the sixties. When I was living then separated from Armand, I went and was very much interested in the waterfront. The St. Lawrence River held a particular poetry and beauty to me and (I) decided to live there with our daughter, Julie. Leonard heard about this place I was living, with crooked floors and a poetic view of the river, and he came to visit me many times. We had tea together many times and mandarin oranges.

to her place near the river

you can hear the boats go by

you can spend the night beside her

And you know she’s half crazy

and she feeds you tea and oranges

that come all the way from China

And just when you mean to tell her

that you have no love to give her

then she gets you on her wavelength

and she lets the river answer

that you’ve always been her lover

Saunders: Leonard Cohen later said that the opening verse of his poem, later to be the song "Suzanne", was a poetic account of the time he spent with her in the Summer of 1965.

Suzanne: One of our mutual friends mentioned to me, ‘Did you hear the wonderful poem that Leonard wrote for you’ or about you and I said no, because I had been away traveling and I wasn’t aware of it. But apparently it got into the attention of Judy Collins, who urged Leonard to write a song based on the poem.

Saunders: When you heard the song as opposed to hearing the poem, did you instantly think, that’s me?

Suzanne: Oh yes, definitely. That was me. That is me still, yes.

Saunders: What did you think about your portrayal?

Suzanne: Flattered somewhat. But I was depicted as I think, in sad terms too in a sense, and that’s a little unfortunate. You know I don’t think I was quite as sad as that, albeit maybe I was and he perceived that and I didn’t.

Saunders: He writes, ‘you know that she’s half crazy but that’s why you want to be there.’ Did that mean half crazy with unhappiness or just eccentric, bohemian? What did he mean, do you think?

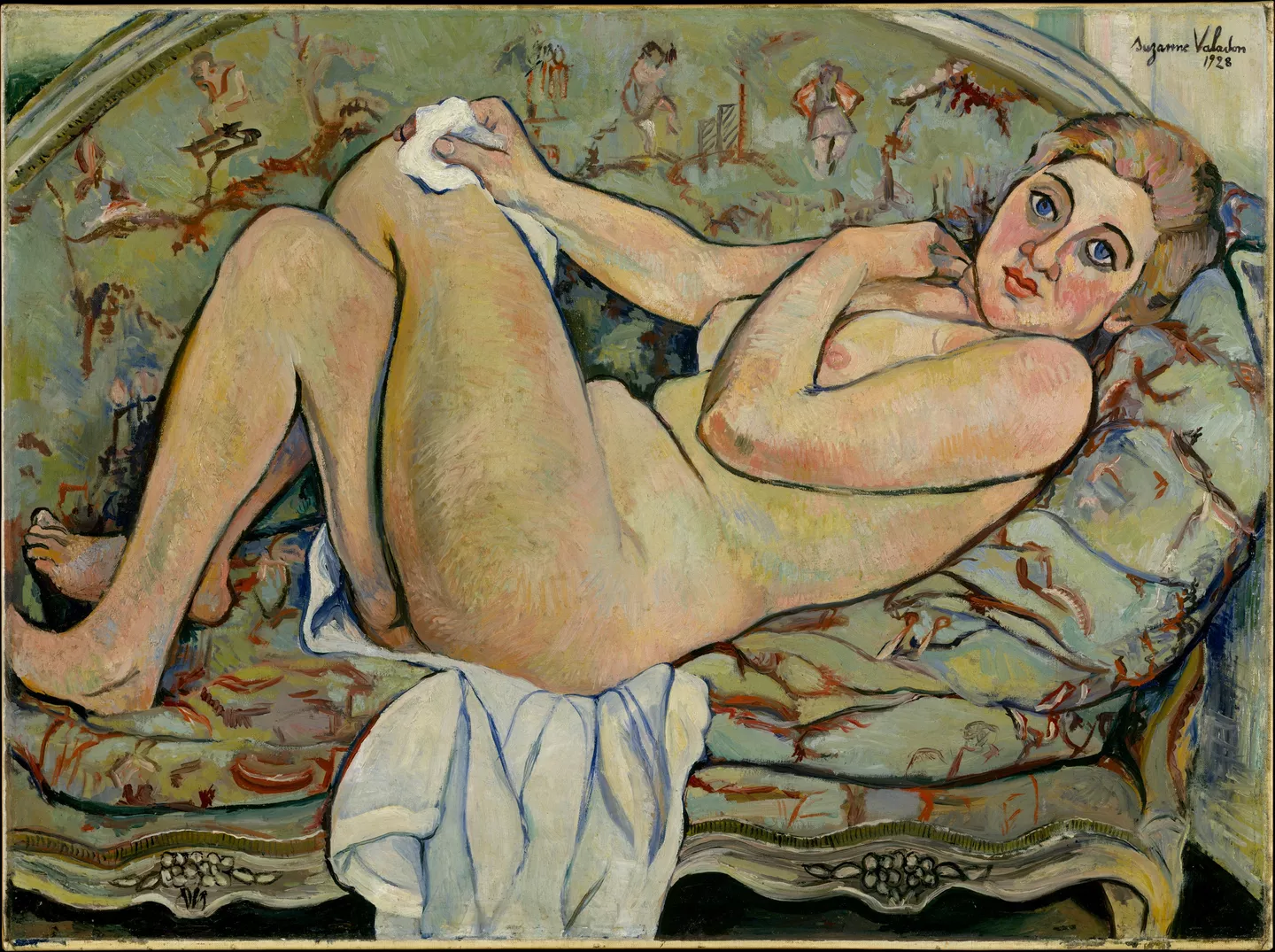

Suzanne: Well, that could be. The half crazy could pertain to the sadness, but I think it was because I was so on a creative drive and the focuses were so strong in spite of any private grief I may have about my break up with Armand and the wheres and whys. There was so much other wonderful things happening. There was the activism. I was already becoming aware of recycling at a very young, young age and I might say, I might be a pioneer in that because I was going to the Salvation Army and getting old dresses and old pieces of just cloth and making something quite wonderful out of them to dress myself, my child, and to make wonderful clothes.

Saunders: Again this is put in the song but then he says, ‘just when you mean to tell her that you have no love to give her, then she gets you on her wavelength and she lets the river answer that you’ve always been her lover.’ What does that mean? Is that something about your level of particular intimacy between you?

Suzanne: Well, I think the river is the river of life and that river, the St. Lawrence River that we shared, tied us together. And it was a union. It was a spirit union.

that come all the way from China

And just when you mean to tell her

that you have no love to give her

then she gets you on her wavelength

and she lets the river answer

that you’ve always been her lover

Now Suzanne takes your hand

and she leads you to the river

she is wearing rags and feathers

from Salvation Army counters

And the sun pours down like honey

on our lady of the harbour

And she shows you where to look

among the garbage and flowers

Suzanne: He was "drinking me in" more than I even recognized, if you know what I mean. I took all that moment for granted. I just would speak and I would move and I would encourage and he would just kind of like sit back and grin while soaking it all up and I wouldn’t always get feedback, but I felt his presence really being with me. We’d walk down the street for instance, and the click of our shoes, his boots and my shoes, would be like in synchronicity. It’s hard to describe. We’d almost hear each other thinking. It was very unique, very, very unique.

Saunders: Could you describe one of the typical evenings that you spent with Leonard Cohen at the time the song was written?

Suzanne: Oh yes. I would always light a candle and serve tea and it would be quiet for several minutes, then we would speak. And I would speak about life and poetry and we’d share ideas.

Saunders: So it really was the tea and oranges that are in the song?

Suzanne: Very definitely, very definitely, and the candle, who I named Anastasia, the flame of the candle was Anastasia to me. Don’t ask me why. It just was a spiritual moment that I had with the lightening of the candle. And I may or may not have spoken to Leonard about, you know I did pray to Christ, to Jesus Christ and to St. Joan at the time, and still do.

Saunders: And that was something you shared, both of you?

Suzanne: Yes, and I guess he retained that.

and she leads you to the river

she is wearing rags and feathers

from Salvation Army counters

And the sun pours down like honey

on our lady of the harbour

And she shows you where to look

among the garbage and flowers

And Jesus was a sailor

when he walked upon the water

and he spent a long time watching

from his lonely wooden tower

and when he knew for certain

only drowning men could see him

he said All men will be sailors then

until the sea shall free them

but he himself was broken

long before the sky would open

forsaken, almost human

he sank beneath your wisdom like a stone

Saunders: After you’d heard this very intimate song, when did you meet Leonard Cohen again, after you’d heard it, and how had your relationship changed, if at all?

Suzanne: It did change. He became a big star after the song was launched and he became a songwriter. As you may or may not know, it launched him as a songwriter, I suppose. Our relationship did change with time. I traveled, went to the U.S., and we’d see him and bump into him. In Minneapolis for instance, he did a concert there and he saw me back stage and received me very beautifully, ‘Oh Suzanne, you gave me a beautiful song.’ And it was a sweet moment. But then there were some bittersweet moments that perhaps I don’t wish to divulge right at this time.

Saunders: You feel that you moved apart after the song?

Suzanne: Yes, and I don’t quite understand. I stayed true to art for art’s sake but he moved on and I stayed true to the cause, as it were. And I guess, I don’t know if that intimidated him or embarrassed him or made him uncomfortable.

Saunders: The song is about the meeting of spirits. It’s a very intimate lyric, very, very intimate.

Suzanne: This is it.

Saunders: It seems very sad that the spirits moved apart.

Suzanne: Yes, I agree and I believe it’s material forces at hand that do this to many the greatest of lovers (laughs).

Saunders: So would you say in a way, in the spiritual sense, you were great lovers at some level?

Suzanne: Oh yes, yes, I don’t hesitate to speak of this, absolutely. As I say, you can glance at a person and that moment is eternal and it’s the deepest of touches and that’s what we’d shared, Leonard and I, I believe.

Saunders: Did either of you ever try to take it a stage further and make it more physically intimate or become lovers? Did either of you ever want to?

Suzanne: Yes, he did, coming from Leonard, it did. Once when he was visiting Montreal, I saw him briefly in a hotel and it was a very, very wonderful, happy moment because he was on his way to becoming the great success he is. And the moment arose that we could have a moment together intimately, and I declined.

when he walked upon the water

and he spent a long time watching

from his lonely wooden tower

and when he knew for certain

only drowning men could see him

he said All men will be sailors then

until the sea shall free them

but he himself was broken

long before the sky would open

forsaken, almost human

he sank beneath your wisdom like a stone

And you want to travel with her

and you want to travel blind

and you know that she will trust you

for you’ve touched her perfect body

with your mind

Saunders: Do you think he resented the fact at all that you turned him down when he did fancy you?

Suzanne: I’ll never really know because there is a part of me that doesn’t understand the male gender, so I can’t speak about that part (laughs). I don’t know for sure. I forget that Leonard is more than just an amazing poet and philosopher. He’s also a human being who happens to be a man (laughs), so I can’t speak on that side.

and you want to travel blind

and you know that she will trust you

for you’ve touched her perfect body

with your mind

There are heroes in the seaweed

there are children in the morning

they are leaning out for love

Saunders: Leonard Cohen finally ended up embracing spiritualism in the Mt. Baldy Zen Monastery in California, only a few miles down the road from where Suzanne now lives with her seven cats and works as a dance instructor and massage therapist.

there are children in the morning

they are leaning out for love

and you want to travel blind

you know that you can trust her

for she’s touched your perfect body

with her mind

Saunders: Do you at all resent the fact that he, if you like, milked you for all the artistic inspiration and then moved on, having created this lovely thing from you? You can almost be said to have created this song yourself.

Suzanne: That may be, but I think poets do that. Poets, when they have a vision or an image, of course, use that. That’s their material. You must do this and being used is not even part of it at the time. That doesn’t exist. What came later was not remaining friends with Leonard and not knowing why. And that’s why there was some ill feeling there or some sadnesses that were not there at the beginning at all. Now the words have more meaning in a sense, because there’s a kind of detachment in the song that I hear now, that I didn’t hear then. Does that make sense to you?

Saunders: It does, indeed. I was going to say, he is almost your audience.

Suzanne: That’s right, absolutely. It’s like an observer, and not the participant any more, yes.

Saundes: Leonard Cohen recently described the song as the best of his whole career. He likened it to a 1982 Chateau Le Tour, a good bottle of wine. What does the song mean to you now, as you look back on it? Do you ever listen to it?

Suzanne: Not recently. There’s a little bit of a bittersweet feeling to it that I retain. I guess I miss the simpler times that we lived and shared. I don’t mean to be maudlin about it, but we’ve kind of gone our different ways and lost touch and some of my most beloved friends have departed from this planet into the other spheres. And there’s sometimes a very real homesickness for Montreal and that wonderful time.

Saunders: So it almost has become a symbol of your youth, if you like?

Suzanne: Oh absolutely, and for many of us, I hold dear this time, very much so.

you know that you can trust her

for she’s touched your perfect body

with her mind