The Road Not Taken

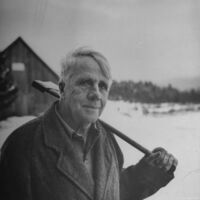

William H. Pritchard

On December 16, 1916, he received a warm letter from Meiklejohn, looking forward to his presence at Amherst and saying that that morning in chapel he had read aloud "The Road Not Taken," "and then told the boys about your coming. They applauded vigorously and were evidently much delighted by the prospect."

Alexander Meiklejohn was an exceptionally high-minded educator whose principles and whose moral tone toward things may be illustrated most briefly and clearly by some statements from his essay "What the College Is." This, his inaugural address as president of Amherst, was printed for a time as an introduction to the college catalogue. What the college was, or should be -what Meiklejohn hoped to make Amherst into - was a place to be thought of as "liberal," that is, "essentially intellectual": "The college is primarily not a place of the body, nor of the feelings, nor even of the will; it is, first of all, a place of the mind." Introducing "the boys" to the intellectual life led for its own sake, would save them from pettiness and dullness, would save them from being one of what Meiklejohn referred to as "the others":

There are those among us who will find so much satisfaction in the countless trivial and vulgar amusements of a crude people that they have no time for the joys of the mind. There are those who are so closely shut up within a little round of petty pleasures they that have never dreamed of the fun of reading and conversing and investigating and reflecting.

A liberal education would rescue boys from stupidity, its purpose being to draw from that "reality-loving American boy" something like "an intellectual enthusiasm." But this result could not be achieved, Meiklejohn added, without a thorough reversal of the curriculum: "I should like to see every freshman at once plunged into the problems of philosophy," he said with enthusiasm.

Now, five years after his address, he was bringing to Amherst someone outside the usual academic orbit, a poet who lacked even a college degree. But despite - or perhaps because of - this lack, the poet had escaped triviality, was an original mind who knew about living by ideas. For he had written among other poems "The Road Not Taken," given pride of place in the just-published Mountain Interval as not only its first poem but also printed in italics, as though to make it also a preface to and motto for the poems which followed. It was perfect for Meiklejohn's purposes because it was no idle reverie, no escape through lovely language into a soothing dream world, but a poem rather which announced itself to be "about" important issues in life: about the nature of choice, of decision, of how to go in one direction rather than another and how to feel about the direction you took and didn't take. For President Meiklejohn and for the assembled students at compulsory chapel, it might have been heard as a stirring instance of what the "liberal college" was all about, since it showed how, instead of acceding to the petty pleasures, the "countless trivial and vulgar amusements" offered by the world or the money-god or the values of the marketplace, an individual could go his own way, live his own life, read his own books, take the less traveled road:

Somewhere ages and ages hence;

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I —

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

The poem ended, the boys "applauded vigorously," and surely Meiklejohn congratulated himself just a bit on making the right choice, taking the less traveled road and inviting a poet to join the Amherst College faculty.

What the president could hardly have imagined, committed as he was in high seriousness to making the life of the college truly an intellectual one, was the unruliness of Frost's spirit and its unwillingness to be confined within the formulas - for Meiklejohn, they were the truths - of the "liberal college." On the first day of the new year, 1917, just preparatory to moving his family down from the Franconia farm into a house in Amherst, Frost wrote Untermeyer about where the fun lay in what he, Frost, thought of as "intellectual activity":

You get more credit for thinking if you restate formulae or cite cases that fall in easily under formulae, but all the fun is outside saying things that suggest formulae that won't formulate - that almost but don't quite formulate. I should like to be so subtle at this game as to seem to the casual person altogether obvious. The casual person would assume I meant nothing or else I came near enough meaning something he was familiar with to mean it for all practical purposes. Well, well, well.

The "fun" is "outside," and lies in doing something like teasing, suggesting formulae that don't formulate, or not quite. The fun is not in being "essentially intellectual" or in manifesting "intellectual enthusiasm" in Meiklejohn's sense of the phrase, but in being "subtle," and not just subtle but so much so as to fool "the casual person" into thinking that what you said was obvious. If we juxtapose these remarks with his earlier determination to reach out as a poet to all sorts and kinds of people, and if we think of "The Road Not Taken" as a prime example of a poem which succeeded in reaching out and taking hold, then something interesting emerges about the kind of relation to other people, to readers - or to students and college presidents - Frost was willing to live with, indeed to cultivate.

For the large moral meaning which "The Road Not Taken" seems to endorse - go, as I did, your own way, take the road less traveled by, and it will make "all the difference"-does not maintain itself when the poem is looked at more carefully. Then one notices how insistent is the speaker on admitting, at the time of his choice, that the two roads were in appearance "really about the same," that they "equally lay / In leaves no step had trodden black," and that choosing one rather than the other was a matter of impulse, impossible to speak about any more clearly than to say that the road taken had "perhaps the better claim." But in the final stanza, as the tense changes to future, we hear a different story, one that will be told "with a sigh" and "ages and ages hence." At that imagined time and unspecified place, the voice will have nobly simplified and exalted the whole impulsive matter into a deliberate one of taking the "less traveled" road:

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

Is it not the high tone of poignant annunciation that really makes all the difference? An earlier version of the poem had no dash after "I"; presumably Frost added it to make the whole thing more expressive and heartfelt. And it was this heartfelt quality which touched Meiklejohn and the students.

Yet Frost had written Untermeyer two years previously that "I'll bet not half a dozen people can tell you who was hit and where he was hit in my Road Not Taken," and he characterized himself in that poem particularly as "fooling my way along." He also said that it was really about his friend Edward Thomas, who when they walked together always castigated himself for not having taken another path than the one they took. When Frost sent "The Road Not Taken" to Thomas he was disappointed that Thomas failed to understand it as a poem about himself, but Thomas in return insisted to Frost that "I doubt if you can get anybody to see the fun of the thing without showing them and advising them which kind of laugh they are to turn on." And though this sort of advice went exactly contrary to Frost's notion of how poetry should work, he did on occasion warn his audiences and other readers that it was a tricky poem. Yet it became a popular poem for very different reasons than what Thomas referred to as "the fun of the thing." It was taken to be an inspiring poem rather, a courageous credo stated by the farmer-poet of New Hampshire. In fact, it is an especially notable instance in Frost's work of a poem which sounds noble and is really mischievous. One of his notebooks contains the following four-line thought:

That unless it's out of sheer

Mischief and a little queer

It wont prove a bore to hear.

The mischievous aspect of "The Road Not Taken" is what makes it something un-boring, for there is little in its language or form which signals an interesting poem. But that mischief also makes it something other than a "sincere" poem, in the way so many readers have taken Frost to be sincere. Its fun is outside the formulae it seems almost but not quite to formulate.

From Frost: A Literary Life Reconsidered. Copyright © 1984 by William Pritchard.

Jay Parini

A close look at the poem reveals that Frost's walker encounters two nearlv identical paths: so he insists, repeatedly. The walker looks down one, first, then the other, "as just as fair." Indeed, "the passing there / Had worn them reallv about the same." As if the reader hasn't gotten the message, Frost says for a third time. "And both that morning equally lay/ In leaves no step had trodden black." What, then, can we make of the final stanza? My guess is that Frost, the wily ironist, is saying something like this: "When I am old, like all old men, I shall make a myth of my life. I shall pretend, as we all do, that I took the less traveled road. But I shall be lying." Frost signals the mockingly self-inflated tone of the last stanza by repeating the word "I," which rhymes - several times - with the inflated word "sigh." Frost wants the reader to know that what he will be saying, that he took the road less traveled, is a fraudulent position, hence the sigh.

From "Frost" in Columbia Literary History of the United States. Ed. Emory Elliott. Copyright © 1988 by the Columbia University Press.George Montiero

"THE ROAD NOT TAKEN" can be read against a literary and pictorial tradition that might be called "The Choice of the Two Paths, " reaching not only back to the Gospels and beyond them to the Greeks but to ancient English verse as well. In Reson and Sensuallyte, for example, John Lydgate explains how he dreamt that Dame Nature had offered him the choice between the Road of Reason and the Road of Sensuality. In art the same choice was often represented by the letter "Y" with the trunk of the letter representing the careless years of childhood and the two paths branching off at the age when the child is expected to exercise discretion. In one design the "Two Paths" are shown in great detail. "On one side a thin line of pious folk ascend a hill past several churches and chapels, and so skyward to the Heavenly City where an angel stands proffering a crown. On the other side a crowd of men and women are engaged in feasting, music, love-making, and other carnal pleasures while close behind them yawns the flaming mouth of hell in which sinners are writhing. But hope is held out for the worldly for some avoid hell and having passed through a dark forest come to the rude huts of Humility and Repentance." Embedded in this quotation is a direct reference to the opening of Dante's Inferno:

I found myself within a forest dark,

For the straightforward pathway had been lost.

Ah me! how hard a thing it is to say

What was the forest savage, rough, and stern,

Which in the very thought renews the fear.

So bitter is it, death is little more.

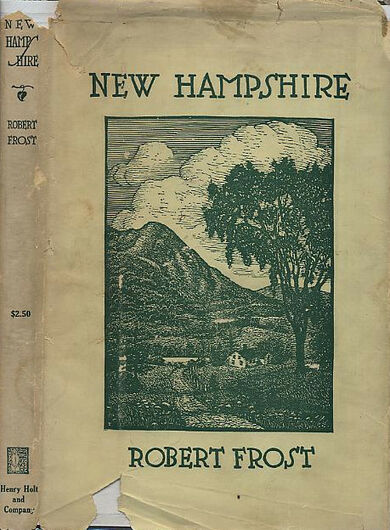

From the beginning, when it appeared as the first poem in Mountain Interval (1916), many readers have overstated the importance of "The Road Not Taken" to Frost's work. Alexander Meiklejohn, president of Amherst College, did so when, announcing the appointment of the poet to the school's faculty he recited it to a college assembly.

"The Choice of Two Paths" is suggested in Frost's decision to make his two roads not very much different from one another, for passing over one of them had the effect of wearing them "really about the same." This is a far cry from, say, the description of the "two waies " offered in the seventeenth century by Henry Crosse:

Two waies are proposed and laide open to all, the one inviting to vertue, the other alluring to vice; the first is combersome, intricate, untraded, overgrowne, and many obstacles to dismay the passenger; the other plaine, even beaten, overshadowed with boughes, tapistried with flowers, and many objects to feed the eye; now a man that lookes but only to the outward shewe, will easily tread the broadest pathe, but if hee perceive that this smooth and even way leads to a neast of Scorpions: or a litter of Beares, he will rather take the other though it be rugged and unpleasant, than hazard himselfe in so great a daunger.

Frost seems to have deliberately chosen the word "roads" rather than "waies" or "paths" or even "pathways." In fact, on one occasion when he was asked to recite his famous poem, "Two paths diverged in a yellow wood," Frost reacted with such feeling—"Two roads!"—that the transcription of his reply made it necessary both to italicize the word "roads" and to follow it with an exclamation point. Frost recited the poem all right, but, as his friend remembered, "he didn't let me get away with 'two paths!'"

Convinced that the poem was deeply personal and directly self-revelatory Frost's readers have insisted on tracing the poem to one or the other of two facts of Frost's life when he was in his late thirties. (At the beginning of the Inferno Dante is thirty-five, "midway on the road of life," notes Charles Eliot Norton.) The first of these, an event, took place in the winter of 1911-1912 in the woods of Plymouth, New Hampshire, while the second, a general observation and a concomitant attitude, grew out of his long walks in England with Edward Thomas, his newfound Welsh-English poet-friend, in 1914.

In Robert Frost: The Trial by Existence, Elizabeth Shepley Sergeant locates in one of Frost's letters the source for "The Road Not Taken." To Susan Hayes Ward the poet wrote on February 10, 1912:

Two lonely cross-roads that themselves cross each other I have walked several times this winter without meeting or overtaking so much as a single person on foot or on runners. The practically unbroken condition of both for several days after a snow or a blow proves that neither is much travelled. Judge then how surprised I was the other evening as I came down one to see a man, who to my own unfamiliar eyes and in the dusk looked for all the world like myself, coming down the other, his approach to the point where our paths must intersect being so timed that unless one of us pulled up we must inevitably collide. I felt as if I was going to meet my own image in a slanting mirror. Or say I felt as we slowly converged on the same point with the same noiseless yet laborious stride as if we were two images about to float together with the uncrossing of someone's eyes. I verily expected to take up or absorb this other self and feel the stronger by the addition for the three-mile journey home. But I didn't go forward to the touch. I stood still in wonderment and let him pass by; and that, too, with the fatal omission of not trying to find out by a comparison of lives and immediate and remote interests what could have brought us by crossing paths to the same point in a wilderness at the same moment of nightfall. Some purpose I doubt not, if we could but have made out. I like a coincidence almost as well as an incongruity.

This portentous account of meeting "another" self (but not encountering that self directly and therefore not coming to terms with it) would eventually result in a poem quite different from "The Road Not Taken" and one that Frost would not publish for decades. Elizabeth Sergeant ties the moment with Frost's decision to go off at this time to some place where he could devote more time to poetry. He had also, she implies, filed away his dream for future poetic use.

That poetic use would occur three years later. In 1914 Frost arrived in England for what he then thought would be an extended sabbatical leave from farming in New Hampshire. By all the signs he was ready to settle down for a long stay. Settling in Gloucestershire, he soon became a close friend of Edward Thomas. Later, when readers persisted in misreading "The Road Not Taken," Frost insisted that his poem had been intended as a sly jest at the expense of his friend and fellow poet. For Thomas had invariably fussed over irrevocable choices of the most minor sort made on daily walks with Frost in 1914, shortly before the writing of the poem. Later Frost insisted that in his case the line "And that has made all the difference"—taken straight—was all wrong. "Of course, it hasn't," he persisted, "it's just a poem, you know." In 1915, moreover, his sole intention was to twit Thomas. Living in Gloucestershire, writes Lawrance Thompson, Frost had frequently taken long countryside walks with Thomas.

Repeatedly Thomas would choose a route which might enable him to show his American friend a rare plant or a special vista; but it often happened that before the end of such a walk Thomas would regret the choice he had made and would sigh over what he might have shown Frost if they had taken a "better" direction. More than once, on such occasions, the New Englander had teased his Welsh-English friend for those wasted regrets. . . . Frost found something quaintly romantic in sighing over what might have been. Such a course of action was a road never taken by Frost, a road he had been taught to avoid.

If we are to believe Frost and his biographer, "The Road Not Taken" was intended to serve as Frost's gentle jest at Thomas's expense. But the poem might have had other targets. One such target was a text by another poet who in a different sense might also be considered a "friend": Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, whose poem, "My Lost Youth," had provided Frost with A Boy's Will, the title he chose for his first book.

"The Road Not Taken " can be placed against a passage in Longfellow's notebooks: "Round about what is, lies a whole mysterious world of might be,—a psychological romance of possibilities and things that do not happen. By going out a few minutes sooner or later, by stopping to speak with a friend at a corner, by meeting this man or that, or by turning down this street instead of the other, we may let slip some great occasion of good, or avoid some impending evil, by which the whole current of our lives would have been changed. There is no possible solution to the dark enigma but the one word, 'Providence.'"

Longfellow's tone in this passage is sober, even somber, and anticipates the same qualities in Edward Thomas, as Frost so clearly perceived. Elizabeth Shepley Sergeant had insisted that Frost's dream encounter with his other self at a crossroads in the woods had a " subterranean connection " with the whole of "The Road Not Taken," especially with the poem's last lines:

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

Undoubtedly. But whereas Longfellow had invoked Providence to account for acts performed and actions not taken, Frost calls attention only to the role of human choice. A second target was the notion that "whatever choice we make, we make at our peril." The words just quoted are Fitz-James Stephen's, but it is more important that Frost encountered them in William James's essay "The Will to Believe." In fact, James concludes his final paragraph on the topic: "We stand on a mountain pass in the midst of whirling snow and blinding mist, through which we get glimpses now and then of paths which may be deceptive. If we take the wrong road we shall be dashed to pieces. We do not certainly know whether there is any right one. What must we do? 'Be strong and of a good courage.' Act for the best, hope for the best, and take what comes. . . . If death ends all, we cannot meet death better." The danger inherent in decision, in this brave passage quoted with clear-cut approval by the teacher Frost "never had," does not playa part in "The Road Not Taken." Frost the "leaf-treader" will have none of it, though he will not refuse to make a choice. Nothing will happen to him through default. Nor, argues the poet, is it likely that anyone will melodramatically be dashed to pieces.

It is useful to see Frost's projected sigh as a nudging criticism of Thomas's characteristic regrets, to note that Frost's poem takes a sly poke at Longfellow's more generalized awe before the notion of what might have happened had it not been for the inexorable workings of Providence, and to see "The Road Not Taken" as a bravura tossing off of Fitz-James Stephen's mountainous and meteorological scenario. We can also project the poem against a poem by Emily Dickinson that Frost had encountered twenty years earlier in Poems, Second Series (1891).

Our feet were almost come

To that odd fork in Being's road,

Eternity by term.

Our pace took sudden awe,

Our feet reluctant led.

Before were cities, but between,

The forest of the dead. Retreat was out of hope,—

Behind, a sealed route,

Eternity's white flag before,

And God at every gate.

Dickinson's poem is straightforwardly and orthodoxically religious. But it can be seen that beyond the "journey" metaphor Dickinson's poem employs diction—"road" and "forest"—that recalls "The Choice of the Two Paths" trope, the opening lines of the Inferno, and Frost's secular poem "The Road Not Taken."

From Robert Frost and the New England Renaissance. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 1988. Copyright © 1988 by the UP of Kentucky.Katherine Kearns

"The Road Not Taken," perhaps the most famous example of Frost’s own claims to conscious irony and "the best example in all of American poetry of a wolf in sheep's clothing." Thompson documents the ironic impulse that produced the poem as Frost's "gently teasing" response to his good friend, Edward Thomas, who would in their walks together take Frost down one path and then regret not having taken a better direction. According to Thompson, Frost assumes the mask of his friend, taking his voice and his posture, including the un-Frostian sounding line, "I shall be telling this with a sigh," to poke fun at Thomas's vacillations; Frost ever after, according to Thompson, tried to bring audiences to the ironic point, warning one group, "You have to be careful of that one; it's a tricky poem - very tricky" (Letters xiv-xv). Thompson's critical evaluation is simply that Frost had, in that particular poem, "carried himself and his ironies too subtly," so that the poem is, in effect, a failure (Letters xv). Yet is it simply that - a too exact parody of a mediocre poetic voice, which becomes among the sentimental masses, ironically, one of the most popularly beloved of Frost's "wise" poems? This is the easiest way to come to terms critically with the popularity of "The Road Not Taken" but it is not, perhaps, the only or best way: in this critical case, the road less traveled may indeed be more productive.

For Frost by all accounts was genuinely fond of Thomas. He wrote his only elegy to Thomas and he gives him, in that poem, the highest praise of all from one who would, himself, hope to be a "good Greek": he elegizes Thomas as "First soldier, and then poet, and then both, / Who died a soldier-poet of your race." He recalls Thomas to Amy Lowell, saying "the closest I ever came in friendship to anyone in England or anywhere else in the world I think was with Edward Thomas" (Letters 220). Frost's protean ability to assume dramatic masks never elsewhere included such a friend as Thomas, whom he loved and admired, tellingly, more than "anyone in England or anywhere else in the world" (Letters 220). It might be argued that in becoming Thomas in "The Road Not Taken," Frost momentarily loses his defensive preoccupation with disguising lyric involvement to the extent that ironic weapons fail him. A rare instance in Frost's poetry in which there is a loved and reciprocal figure, the poem is divested of the need to keep the intended reader at bay. Here Frost is not writing about that contentiously erotic love which is predicated on the sexual battles between a man and a woman, but about a higher love, by the terms of the good Greek, between two men. As Plato says in the Symposium (181, b-c), "But the heavenly love springs from a goddess [Aphrodite] whose attributes have nothing of the female, but are altogether male, and who is also the elder of the two, and innocent of any hint of lewdness. And so those who are inspired by this other Love turn rather to the male, preferring the more vigorous and intellectual bent." If the poem is indeed informed by such love, it becomes the most consummate irony of all, as it shows, despite one level of Frost's intentions, how fraternal love can transmute swords to plowshares, how, indeed, two roads can look about the same, be traveled about the same, and be utterly transformed by the traveler. Frost sent this poem as a letter, as a communication in the most basic sense, to a man to whom he says, in "To E. T.," "I meant, you meant, that nothing should remain / Unsaid between us, brother . . . " When nothing is meant to remain unsaid, and when the poet's best hope is to see his friend "pleased once more with words of mine," all simple ironies are made complex. "The Road Not Taken," far from being merely a failure of ironic intent, may be seen as a touchstone for the complexities of analyzing Frost's ironic voices.

From Robert Frost and a Poetics of Appetite. Copyright © 1994 by Cambridge University Press. Reprinted by permission of the author.Frank Lentricchia

Self-reliance in "The Road Not Taken" is alluringly embodied as the outcome of a story presumably representative of all stories of self-hood, and whose central episode is that moment of the turning-point decision, the crisis from which a self springs: a critical decision consolingly, for Frost's American readers, grounded in a rational act when a self, and therefore an entire course of life, are autonomously and irreversibly chosen. The particular Fireside poetic structure in which Frost incarnates this myth of selfhood is the analogical landscape poem, perhaps most famously executed by William Cullen Bryant in "To a Waterfowl," a poem that Matthew Arnold praised as the finest lyric of the nineteenth century and that Frost had by heart as a child thanks to his mother's enthusiasm.

The analogical landscape poem draws its force from the culturally ancient and pervasive idea of nature as allegorical book, in its American poetic setting a book out of which to draw explicit lessons for the conduct of life (nature as self-help text). In its classic Fireside expression, the details of landscape and all natural events are cagily set up for moral summary as they are marched up to the poem's conclusion, like little imagistic lambs to slaughter, for their payoff in uplifting message. Frost appears to recapitulate the tradition 'in his sketching of the yellow wood and the two roads and in his channeling of the poem's course of events right up to the portentous colon ("Somewhere ages and ages hence:") beyond which lies the wisdom that we jot down and take home:

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

If we couple such tradition-bound thematic structure with Frost's more or less conventional handling of metric, stanzaic form and rhyme scheme, then we have reason enough for Ellery Sedgwick's acceptance of this poem for the Atlantic: no "caviar to the crowd" here.

And yet Frost has played a subtle game in an effort to have it both ways. In order to satisfy the Atlantic and its readers, he hews closely to the requirements of popular genre writing and its mode of poetic production, the mass circulation magazine. But at the same time he has more than a little undermined what that mode facilitates in the realm of American poetic and political ideals. There must be two roads and they must, of course, be different if the choice of one over the other is to make a rational difference ("And that has made all the difference"). But the key fact, that on the particular morning when the choice was made the two roads looked "about the same," makes it difficult to understand how the choice could be rationally grounded on (the poem's key word) perceptible, objective "difference." The allegorical "way" has been chosen, a self has been forever made, but not because a text has been "read" and the "way" of nonconformity courageously, ruggedly chosen. The fact is, there is no text to be read, because reading requires a differentiation of signs, and on that morning clear signifying differences were obliterated. Frost's delivery of this unpleasant news has long been difficult for his readers to hear because he cunningly throws it away in a syntax of subordination that drifts out of thematic focus. The unpleasant news is hard to hear, in addition, because Fireside form demands, and therefore creates the expectation of, readable textual differences in the book of nature. Frost's heavy investment in traditional structure virtually assures that Fireside literary form will override and cover its mischievous handling in this poem.

For a self to be reliant, decisive, nonconformist, there must already be an autonomous self out of which to propel decision. But what propelled choice on that fateful morning? Frost's speaker does not choose out of some rational capacity; he prefers, in fact, not to choose at all. That is why he can admit to what no self-respecting self-reliant self can admit to: that he is "sorry" he "could not travel both/And be one traveler." The good American ending, the last three lines of the poem, is prefaced by two lines of storytelling self-consciousness in which the speaker, speaking in the present to a listener (reader) to whom he has just conveyed "this," his story of the past - everything preceding the last stanza - in effect tells his auditor that in some unspecified future he will tell it otherwise, to some gullible audience, tell it the way they want to hear it, as a fiction of autonomous intention.

The strongly sententious yet ironic last stanza in effect predicts the happy American construction which "The Road Not Taken" has been traditionally understood to endorse — predicts, in other words, what the poem will be sentimentally made into, but from a place in the poem that its Atlantic Monthly reading, as it were, will never touch. The power of the last stanza within the Fireside teleology of analogical landscape assures Frost his popular audience, while for those who get his game — some member, say, of a different audience, versed in the avant-garde little magazines and in the treacheries of irony and the impulse of the individual talent trying, as Pound urged, to "make it new" against the literary and social American grain - for that reader, this poem tells a different tale: that our life-shaping choices are irrational, that we are fundamentally out of control. This is the fabled "wisdom" of Frost, which he hides in a moralizing statement that asserts the consoling contrary of what he knows.

From Frank Lentricchia, Modernist Quartet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995: 71-74.Mark Richardson

The ironies of this poem have been often enough remarked. Not least among them is the contrast of the title with the better-remembered phrase of the poem's penultimate line: "the [road] less travelled by" (CPPP 103). Which road, after all, is the road "not taken"? Is it the one the speaker takes, which, according to his last description of it, is "less travelled"-that is to say, not taken by others? Or does the title refer to the supposedly better-traveled road that the speaker himself fails to take? Precisely who is not doing the taking? This initial ambiguity sets in play equivocations that extend throughout the poem. Of course, the broadest irony in the poem derives from the fact that the speaker merely asserts that the road he takes is "less travelled": the second and third stanzas make clear that "the passing there" had worn these two paths "really about the same" and that "both that morning equally lay / In leaves no step had trodden black." Strong medial caesurae in the poem's first ten lines comically emphasize the "either-or" deliberations in which the speaker is engaged, and which have, apparently, no real consequence: nothing issues from them. Only in the last stanza is any noticeable difference between the two roads established, and that difference is established by fiat: the speaker simply declares that the road he took was less travelled. There is nothing to decide between them. There is no meaningful "choice" to make, or rather no more choice than is meaningfully apparent to the "step-careless" politician of Frost's parable of decision in "The Constant Symbol."

Comical as "The Road Not Taken" may be, there is serious matter in it, as my reading of "The Constant Symbol" is meant to suggest. "Step-carelessness" has its consequences; choices—even when they are undertaken so lightly as to seem unworthy of the name "choice"—are always more momentous, and very often more providential, than we suppose. There may be, one morning in a yellow wood, no difference between two roads—say, the Democratic and the Republican parties. But "way leads on to way," as Frost's speaker says, and pretty soon you find yourself in the White House. As I argue throughout this chapter, this is the indifference that Frost wants us to see: "youthful step-carelessness" really is a form of "step-carefulness." But it is only by setting out, by working our way well into the wood, that we begin to understand the meaning of the choices we make and the character of the self that is making them; in fact, only then can we properly understand our actions as choices. The speaker vacillates in the first three stanzas of "The Road Not Taken," but his vacillations, viewed in deeper perspective, seem, and in fact really are, "decisive." We are too much in the middle of things, Frost seems to be saying, ever to understand when we are truly "acting" and "deciding" and when we are merely reacting and temporizing. Our paths unfold themselves to us as we go. We realize our destination only when we arrive at it, though all along we were driven toward it by purposes we may rightly claim, in retrospect, as our own. Frost works from Emerson's recognition in "Experience":

Where do we find ourselves? In a series of which we do not know the extremes, and believe that it has none. We wake and find ourselves on a stair; there are stairs below us, which we seem to have ascended; there are stairs above us, many a one, which go upward and out of sight. But the Genius which, according to the old belief, stands at the door by which we enter, and gives us the lethe to drink, that we may tell no tales, mixed the cup too strongly, and we cannot shake off the lethargy now at noonday. ...If any of us knew what we were doing, or where we are going, then when we think we best know! We do not know today whether we are busy or idle. In times when we thought ourselves indolent, we have afterwards discovered, that much was accomplished, and much was begun in us. (Essays 471)

Frost's is an Emersonian philosophy in which indecisiveness and decision feel very much alike—a philosophy in which acting and being acted upon form indistinguishable aspects of a single experience. There is obviously a contradiction in "The Road Not Taken" between the speaker's assertion of difference in the last stanza and his indifferent account of the roads in the first three stanzas. But it is a contradiction more profitably described—in light of Frost's other investigations of questions about choice, decision, and action—as a paradox. He lets us see, as I point out above, that every action is in some degree intemperate, incalculable, "step-careless." The speaker of "The Road Not Taken," like the politician described in "The Constant Symbol," is therefore a figure for us all. This complicates the irony of the poem, saving it from platitude on the one hand (the M. Scott Peck reading) and from sarcasm on the other (the biographical reading of the poem merely as a joke about Edward Thomas). I disagree with Frank Lentricchia's suggestion in Modernist Quartet that "The Road Not Taken" shows how "our life- shaping choices are irrational, that we are fundamentally out of control" (75). The author of "The Trial by Existence" would never contend that we are fundamentally out of control—or at least not do so in earnest.

From The Ordeal of Robert Frost: The Poet and His Poetics. Copyright © 1997 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois.Robert Faggen

"The Road Not Taken" is an ironic commentary on the autonomy of choice in a world governed by instincts, unpredictable contingencies, and limited possibilities. It parodies and demurs from the biblical idea that God is the "way" that can and should be followed and the American idea that nature provides the path to spiritual enlightenment. The title refers doubly to bravado for choosing a road less traveled but also to regret for a road of lost possibility and the eliminations and changes produced by choice. "The Road Not Taken " reminds us of the consequences of the principle of selection in al1 aspects of life, namely that al1 choices in knowledge or in action exclude many others and lead to an ironic recognitions of our achievements. At the heart of the poem is the romantic mythology of flight from a fixed world of limited possibility into a wilderness of many possibilities combined with trials and choices through which the pilgrim progresses to divine perfection. I agree with Frank Lentricchia's view that the poem draws on "the culturally ancient and pervasive idea of nature as allegorical book, out of which to draw explicit lessons for the conduct of life (nature as self-help text)." I would argue that what it is subverting is something more profound than the sentimental expectations of genteel readers of fireside poetry. . . .

The drama of the poem is of the persona making a choice between two roads. As evolved creatures, we should be able to make choices, but the poem suggests that our choices are irrational and aesthetic. The sense of meaning and morality derived from choice is not reconciled but, rather obliterated and canceled by a nonmoral monism. Frost is trying to reconcile impulse with a con- science that needs goals and harbors deep regrets. The verb Frost uses is taken, which means something less conscious than chosen. The importance of this opposition to Frost is evident in the way he changed the tide of "Take Something Like a Star" to "Choose Something Like a Star," and he continued to alter tides in readings and publications. Take suggests more of an unconscious grasp than a deliberate choice. (Of course, it also suggests action as opposed to deliberation.) In "The Road Not Taken" the persona's reasons wear thin, and choice is confined by circumstances and the irrational:

[lines 1-10]

Both roads had been worn "about the same," though his "taking" the second is based on its being less worn. The basis of selection is individuation, variation, and "difference": taking the one "less traveled by." That he "could not travel both / And be one traveler" means not only that he will never be able to return but also that experience alters the traveler; he would not be the same by the time he came back. Frost is presenting an antimyth in which origin, destination, and return are undermined by a nonprogressive development. And the hero has only illusory choice. This psychological representation of the developmental principle of divergence strikes to the core of Darwinian theory. Species are made and survive when individuals diverge from others in a branching scheme, as the roads diverge for the speaker. The process of selection implies an unretracing process of change through which individual kinds are permanently altered by experience. Though the problem of making a choice at a crossroads is almost a commonplace, the drama of the poem conveys a larger mythology by including evolutionary metaphors and suggesting the passage of eons.

The change of tense in the penultimate line—to took—is part of the speaker's projection of what he "shall be telling," but only retrospectively and after "ages and ages." Though he cannot help feeling free in selection, the speaker's wisdom is proved only through survival of an unretraceable course of experience:

[lines 11-20]

The poem leaves one wondering how much "difference" is implied by all, given that the "roads" already exist, that possibilities are limited. Exhausted possibilities of human experience diminish great regret over "the road not taken" or bravado for "the road not taken" by everyone else. The poem does raise questions about whether there is any justice in the outcome of one's choices or anything other than aesthetics, being "fair," in our moral decisions. The speaker's impulse to individuation is mitigated by a moral dilemma of being unfair or cruel, in not stepping on leaves, "treading" enough to make them "black. " It might also imply the speaker's recognition that individuation will mean treading on others.

From Robert Frost and the Challenge of Darwin. Copyright © 1997 by The University of Michigan